Have you noticed those porcelain flowers with such delicate colors adorning many objects from the mid-18th century? They reflect the Rococo taste of the Louis XV period and the expansion of porcelain factories in Europe, notably those of Meissen and Vincennes. These objects also arose from the ingenuity of marchands-merciers, who saw in these floral decorations an opportunity to enhance functional items by tapping into the Rococo style and creating a trend.

The Fleurisserie in Vincennes, a Workshop Specialized in Porcelain Flowers

At first in France, the porcelain flowers added to functional or purely decorative objects were called flowers «façon de Saxe». Indeed, such flowers were first made around 1730 by the “Royal-Polish and Electoral-Saxon Porcelain Manufactory” in Meissen in hard-paste porcelain.

A pair of Meissen porcelain vases with porcelain flowers from the 18th century (Louis XV period). © Nicolas Bordet

As porcelain, also nicknamed “white gold,” was so dearly valued in Europe, each country wanted to uncover the Chinese secret recipe for its making. In France, after the first factory developed by Louis-Henri of Bourbon-Condé in Chantilly, the porcelain epicenter became Vincennes in 1740; the porcelain from there was soon called «porcelaine de France» as the factory was nationalized in 1751. Vincennes only produced a soft-paste porcelain not made from kaolin.

The fleurisserie at the Manufacture de Vincennes was a workshop dedicated to creating flowers in porcelain within the factory. It was active only from 1748 to 1753, though production of porcelain flowers at the factory had already begun in 1741. These flowers were a main source of revenue for Vincennes.

64 types of flowers in soft porcelain were developed at the fleurisserie of Vincennes. They were crafted using a technique called pastillage, in which each petal was individually shaped from a small ball of porcelain paste. The flowers were white or polychromatic. Vincennes (and later Sèvres) was renowned for its color palette thanks to the excellent mastery of low-temperature color firing (an advantage of soft-paste porcelain over hard-paste).

An 18th-century candle holder to hook on a screen. With Vincennes porcelain flowers and red lacquer. © Galerie Pellat de Villedon

The workshop was led by Henriette Gravant, the spouse of one of the factory founders. The flowers were made by women in their homes and brought back to be fired and decorated in the factory. We know for instance that over 1,000 flowers were decorated in the second half of 1748. Mrs. Gravant had a team of about 45 workers in 1749. The flowers were then mounted on cannetille (fine, twisted metal) stems covered with silk leaves.

The Taste of the Marchands Merciers

The marchands merciers as traders, importers, art dealers, and tastemakers were essential to the consumption and commercial success of the porcelain flowers. In 1783 in an encyclopedia, the marchands merciers were defined as:

Marchands-merciers can embellish all the goods they sell, but not manufacture them.

These merchants served as the essential link between craftsmen and their elite clientele in the luxury goods market. They traded in a wide variety of items—furniture in the broadest sense, including decorative objects, as well as artworks and home textiles. They worked with many suppliers, such as cabinetmakers, watchmakers, bronziers, artists, and factories. In their workshops, they assembled creations from the materials they had acquired.

Antoine Watteau represented in 1720 a promotional view of his friend’s shop interior, the marchand-mercier Edme-François Gersaint. Here is a detail of his painting known as “The Store Sign of Gersaint.” © Charlottenburg Castle, SPSG

The porcelain flowers were used in several manners. They were arranged in sumptuous imperishable bouquets in vases or planters or integrated in various compositions. As mentioned in the “Livre-journal de Lazare Duvaux, marchand bijoutier ordinaire du roy, 1748-1758” published in 1873 by Louis courajod:

Considering the people who had him assemble Vincennes flowers, and by examining the descriptions of the pieces he delivered, one can affirm that Duvaux was among the first to produce these branches gilded with ormolu or varnished naturally, these cannetille plants, and these artificial bouquets which, for a time, gave rooms the appearance of gardens or conservatories. To complete the illusion, nothing was missing from these bouquets, not even the scent, which could be artificially imparted to them.

This audacious porcelain bouquet was made by the Vincennes manufactory in 1749. This is a gift sent by Dauphine Maria Josepha to her father King Augustus III. © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Photograph: Jürgen Karpinski

As an early example, we know that such a bouquet was delivered in May 1747 to Count Carl Gustav Tessin—a Swedish francophile art collector who was the Prime Minister of Sweden from 1746 to 1752—by the distinguished French merchant Edme-François Gersaint. Others were delivered to Madame de Pompadour or Queen Marie Leczinska. Ironically, the Dauphine of France Maria Josepha of Saxony offered a bouquet in 1749 to her father Augustus III, owner of the Meissen porcelain factory. Most of these bouquets were dismantled and reused in the 19th century.

Porcelain flowers, however, were mainly used to adorn everyday objects, especially those related to lighting, such as candelabras, wall sconces, and chandeliers. Painted sheet metal, gilt bronze, copper, or brass were used for the stems and leaves. They were added to potpourri vases (a new accessory of the 18th century), clocks, inkwells, or else, sometimes associated with porcelain figurines from Saxony (meaning from Meissen).

An 18th-century clock with Vincennes porcelain flowers, a Meissen porcelain figurine, and a candle holder in gilt bronze. © Galerie Pellat de Villedon

There was no limit to the versatility of these flowers, as they could be virtually added to any object. These arrangements reflected the merchants’ taste and inventiveness, showcasing their choice of objects, decorative elements, and the harmony within each composition.

From Chinese Imports to Chinoiseries

These two Laughing Buddhas (in reality, Budais) sit amidst porcelain flowers on gilt branches. The Vincennes flowers echo the flowers painted on the monks’ robes. The porcelain buddhas were made in China. These highly decorative candelabras beautifully epitomize the fusion of Chinese elements with the refined craftsmanship and taste of 18th-century France. Only the marchands merciers could compose such elaborate and exotic artefacts.

A pair of candelabras in gilt bronze from the mid-18th century. The arms are decorated with porcelain flowers from Vincennes. Porcelain buddhas from the Yongzheng period (1723-1735) sit before them. © Dr Jansen Kunsthandel

We showed earlier that the Vincennes porcelain was sometimes associated with the Meissen porcelain coming from Saxony—now Germany near the Czech and Polish borders. To do that in a world where professions were strictly regulated, you needed to be granted the official privilege to import, which was the case for the marchands merciers guild. And in particular, since 1324, these merchants were allowed to import oriental pieces.

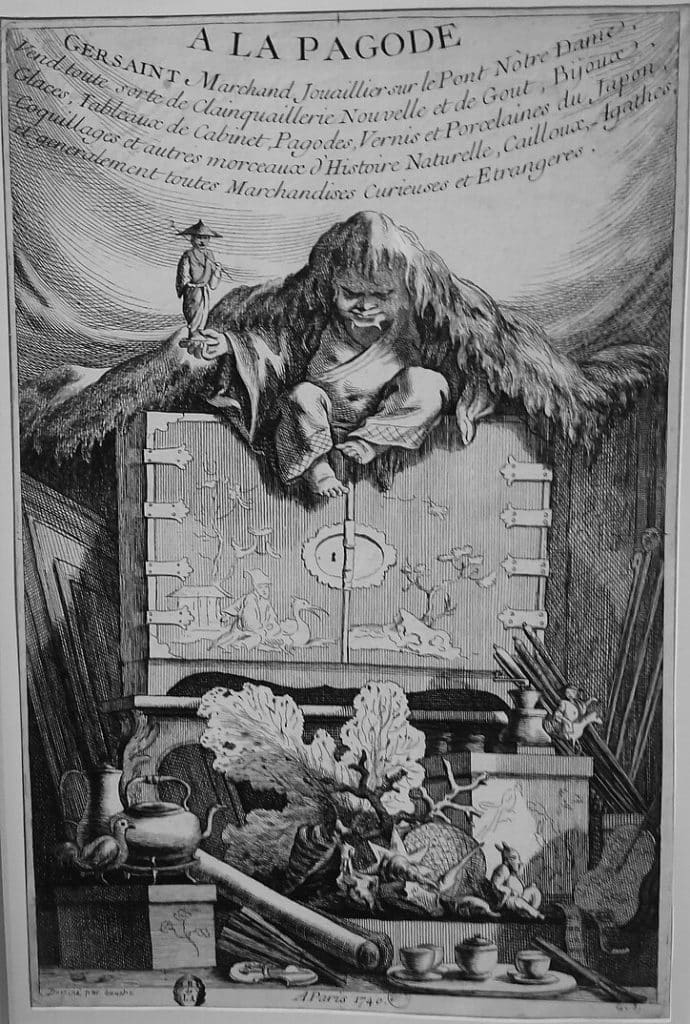

In 1740, François Boucher drew the visit card/label for Edme-François Gersaint’s shop “A la pagode” where he was selling curiosities and oriental imports. Engraved by the count of Caylus. Public Domain

What a lucrative advantage in an 18th century fascinated by the Orient and Far East! This trade was an opportunity to supply decor that captivated clients with dreams of distant lands and customs. Reality was intertwined with fantasy: Chinese and Japanese (or other oriental countries) goods were mixed with chinoiseries. Porcelain and lacquer were at the center of this cultural blend.

18th-century lacquered turned wood potpourri holder with porcelain flowers. © Nicolas Bordet

Chinese, and oriental goods in general, shaped the European taste. Flowers were key motifs in oriental textiles and ceramics imported by the marchands merciers. They inspired the European artists who injected them profusely in the rococo style.

The painter François Boucher, a central artistic figure of rocaille was an avid collector of Asian objects and artworks. When he passed in 1771, he owned over 700 Asian pieces of different materials and purposes. Boucher used these objects as a source of inspiration for many Chinese scenes he created (e.g. for the Beauvais tapestry factory). Thus, when the marchands merciers gave extra life to Chinese imports with porcelain flowers created in France, they closed the cultural hybridization loop.

The Flowers in French Rococo

These flowers in porcelain are distinctly rocaille, the French rococo, that flourished during this period. Of course, flowers and leaves have always been a major ornamental source for decorative arts. Can we even think of a time when they were not used? Yet, rococo has a special connection with flowers.

Rococo is infused with nature. Rocaille stands for the rocks, stones, and shells that inspired this style that bloomed thanks to the ornementalists (Nicolas Pineau, Jacques de Lajoüe, Juste Aurèle Meissonnier, Jean Mondon, François de Cuvilliès, etc.). The energy and unpredictability of nature are also rendered through the asymmetry of the style. The curves and counter-curves of foliage are perfect for these dynamics. Flowers burst where needed. The diversity of their shapes and colors provides endless inspiration.

“Three Ladies by a Stream”, a print of François Boucher by Gilles Demarteau (1722-1776), N°346. Printed in the style of red and black chalk. © Antiques d’Avignon

The spirit of rococo is one of lightness. The star painters of rococo depicted elegant courtly parties or lovers in gardens or nature—for instance, Antoine Watteau with his fêtes galantes and François Boucher with his pastorales. It talks about an idealized world where hardship is nowhere to be seen. Even shepherds dress like princes. The paintings offer a profusion of details and colors that evoke joy and fulfillment.

Flowers were usually inserted thanks to flower beds, bushes, or cornucopia. The characters wore them in crowns, garlands, or necklaces, and carried them in baskets or their apron. François Boucher first inspired the Manufacture de Vincennes with mythological scenes. Towards 1749, he started to work on pastoral scenes with children (a style encouraged by Mme de Pompadour who was so fond of children) for which he provided drawings for the factory. We understand how objects with porcelain flowers perfectly fit in these types of decor.

####

In the 18th century, the rococo style gave way to greater sobriety with Neoclassicism (although, flowers were of course never banned from decor). Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard came to be dismissed as overly sentimental. Meanwhile, the guild of marchands-merciers was dissolved in 1791 during the French Revolution.

As time passes, things change. But fashions, as we know, return. By the late 19th century, within an eclectic artistic environment that didn’t shy away from elaborate decor, rococo made a strong comeback including the porcelain flowers and chinoiseries.

The Samson ceramic factory was particularly successful from the mid-19th century to the First World War for its high-quality artwork reproduction of previous eras, many inspired by the 18th century. Above is a perfume bottle with porcelain flowers. © Olivier d’Ythurbide et Associé

####

You May Like

Porcelain Objects & China | Vincennes Porcelain | Sèvres Porcelain | Meissen Porcelain