When you see a bottle of champagne, you instantly understand there is something to celebrate. Everything in it is joyful: the pop of the cork, the light yellow color, and the bubbles of the wine. For such a special beverage, equally worthy vessels had to be created.

While flutes and coupe glasses are the glassware most commonly associated with champagne, wine glasses are also a viable option. In fact, oenologists even recommend a specific shape, which we’ll reveal later in this article. Let’s explore how different types of champagne glasses have evolved since the 18th century and trace the shifts in their popularity over time.

Champagne Is a Wine, So It Started With a Wine Glass

Sparkling wine from Champagne has always been regarded as a luxury good. First, because it was fairly uncommon: red or white wine from Champagne was primarily not sparkling in the 17th and even the 18th century—in terms of volume. “Brisk champagne” (mousseux) was initially the product of a fermentation process we didn’t have much control over. In France, the taste for sparkling wine seems to grow towards the very end of the 17th century (circa 1695).

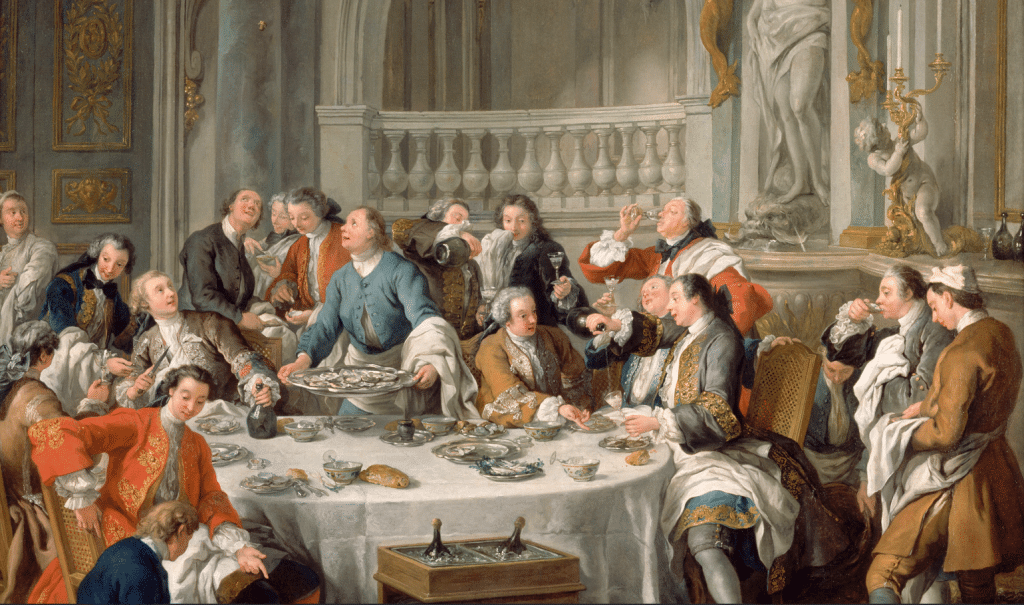

Detail of “Luncheon with oysters”, a 1735 oil painting by Jean-François de Troy. The guests have oysters with champagne. A champagne cork just popped towards the left of the painting. Glasses are already full of champagne from other bottles. The funnel wine glasses are left in individual rafraichissoirs when not held in hands. © Musée Condé in Chantilly

The appetite was awakened by the astonishing effects of wines that popped their corks with a noise and impetuosity so remarkable they hit the ceiling, spilling above the neck like a fountain and emptying half the bottle in the process.

— Valentin-Philippe Bertin du Rocheret (1693-1752)

In 1734, when Bertin du Rocheret, a supplier of champagne wines, wrote this quote above in his correspondence with Abbé Bignon (a distinguished figure who held notable positions and even hosted King Louis XV at his table), sparkling champagne was still in its infancy.

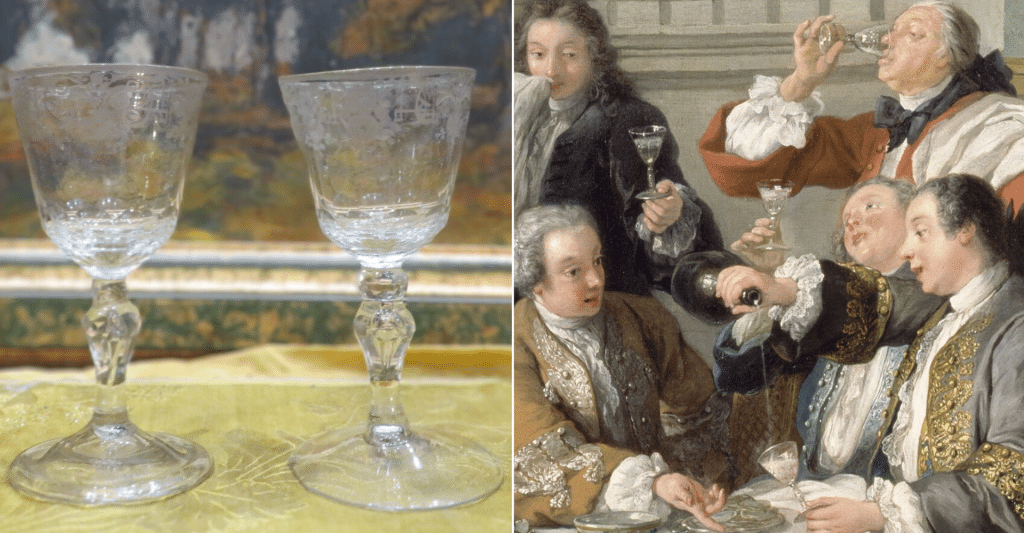

It is remarkable how the “Luncheon with oysters” painting by Jean-François de Troy appears to be the perfect representation of Bertin’s description. Getting a closer look at the glasses, we notice that they are still wine glasses. The conic or bell shape for the bowl and the inverted baluster stem are typical of this period.

On the left, the 18th-century crystal wine glasses are engraved and faceted (© Frédéric Marceau Antiquités). They resemble the glasses used in the oyster lunch painting on the right.

The English Taste for Champagne: A Key Influence

The English were likely the trailblazers of sparkling Champagne wine with a lead of forty good years over the French with sources hinting at its consumption since the 1660s. They were importing the champagne in barrels and handling the bottling process themselves using thicker glass bottles with a long neck and corks (instead of wood bottle stoppers).

Managing this process, the English appreciated and encouraged the transition from still wine to sparkling wine. Regarding the making of champagne, Dom Pérignon (1638-1715) is traditionally regarded as the father of champagne. In reality, while the French Benedictine monk brought much to wine blending and the overall quality of the wine from Champagne, he didn’t focus on the sparkling aspect (in fact, he rather considered the fizz and its original fermentation as an issue for the champagne’s overall quality).

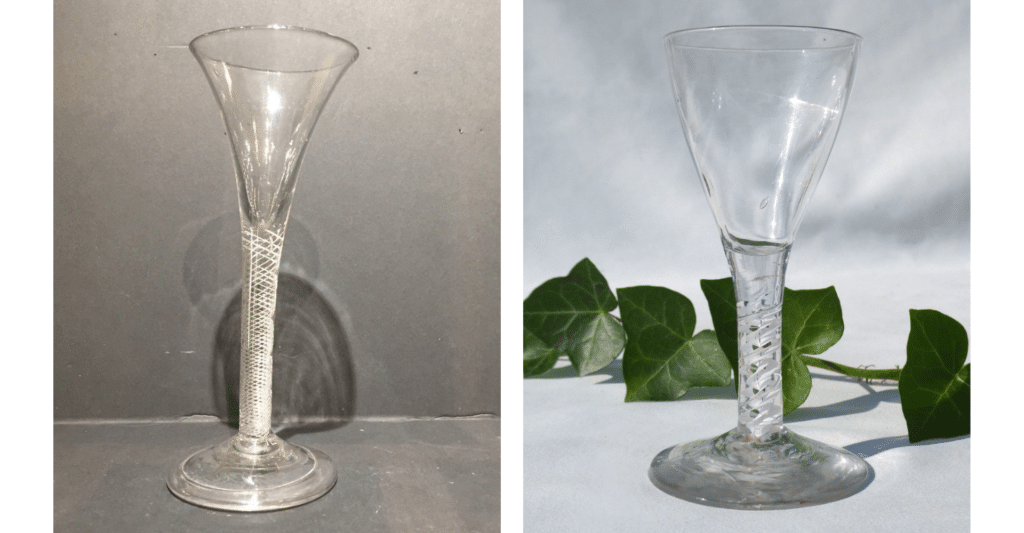

Two classic 18th-century English glasses with twist stems. An air twist stem on the left (© Mazereeuw Antiquair). An air twist surrounding an opaque twist on the right (© Le Bûcher des Vanités).

Returning to the English influence over champagne, their likings, and skillful glassware craftsmanship also impacted the types of glasses used for drinking champagne. The ale or cider glasses anterior to those used for champagne were tall and often had a fluted bowl (pilsner style). The stems were relatively thick (which enabled the highly regarded English twist stems) and seamlessly extended from the conical bowls.

A Distinctive Glass for Champagne: The Flute

Consistent with their early liking for the bubbly wine of Champagne, the English led the way in transforming the conic wine glass into a higher glass in the 1750s called champagne flute as early as 1773. The higher and narrower flute glass specifically for champagne was acknowledged in France at the onset of the 19th century.

An 18th-century blown glass flute. Embossed and hollow down to the glass foot. 13.5 cm long. © MB Antique

Overall, the flute has been the predominant type of champagne glass. The tall glasses delight the sight of the drinkers as the bubbles elegantly trace trails to the wine surface. The wine’s effervescence can then spread through the spirits. Flute designs have evolved significantly from the original conical funnel, which itself inspired numerous variations with straight or flared bowls of varying degrees.

Champagne flutes with bulbous bellies. On the left: 18th-century crystal gilt with festoons (© Catherine Daveau-Bitton). On the right: Art Nouveau blown glass with Venitian stripes and morning glory bases (© Eclecticnimes).

If not a funnel, the bowl can be round or bulbous (a positive factor in developing and concentrating aromas). Like wine glasses, they have been sometimes engraved or decorated with gilt. As crystal glass emerged and grew (England pioneered lead glass towards the end of the 17th century; it officially started in 1782 in France), the brilliance of this material was enhanced with cuts.

Tommy by Saint-Louis is a model created in 1928. It boasts a remarkable array of different cuts in the crystal: diamond, almond, filet, cord and pearl, and a star on the foot. Six different colors are presented here out of the 8 options (and colorless crystal). © L’Ile du Temps

The Champagne Coupe, Not Molded From a Breast

You may have heard the myth that the first champagne coupe was modeled after the breast of Madame de Pompadour or Queen Marie-Antoinette. It’s time to discard this quirky and outdated assumption.

The champagne coupe made its debut in the early 1830s in Europe. It was famously described by Benjamin Disraeli—a prominent British politician active from the 1830s to 1880— as “a saucer of ground glass mounted on a pedestal of cut glass”. It became popular in the 1840s. The shape was inspired by the medieval hanap (or tazza) that inspired saucers to serve desserts (custards, sorbets, fruits).

The Harcourt champagne coupe by Baccarat was created in 1841 for a wedding and officially included in Baccarat’s catalog in 1925. Flat-ribbed and hexagonal leg and foot, perfect for catching and reflecting light. © Adele de Luca

The coupe enjoyed tremendous popularity for nearly a century, remaining in vogue until the 1930s or even the Second World War. By the mid-19th century in France, the Russian-style service replaced the French-style service: all the glasses were placed on the table at the start of a meal, rather than being brought out progressively to the guests. In this impressive arrangement, the champagne coupe stood out, distinctly different from other wine or water glasses. The glassmakers did not miss this opportunity to add a new glass type (offered in numerous variations) to their catalogs.

Eleven champagne crystal coupes of the Vendôme line by Saint-Louis. A 24-pointed star on the foot echoes the parison’s cuts. © MissLittleBottle Antiquités

The coupe glasses also meant beautiful festive buffets with glasses that could be arranged in pyramids to create stunning champagne fountains. What could be more visual than that to express joy in a celebration? For sure, champagne can be the life of a party!

However, the true amateurs for champagne quickly realized that the overly wide shape of the coupe allowed the bubbles and aromas to escape too rapidly.

A Tulip Glass for Champagne

Currently, oenologists agree that a wine glass with a bowl wider at the shoulder than at the rim—commonly referred to as a tulip glass—is ideal. This design allows aromas to develop freely over the wine’s surface. As the aromas rise toward the rim, the narrowing shape of the glass helps concentrate them for the smell and the tasting as some overpowering alcohol molecules roll down.

These crystal glasses, Athena by Baccarat, were designed by Thomas Bastide in 1987. The golden threads and ribbed stems give them a classic flair. Left to right: champagne flute, water, red wine, and white wine glasses. The shape is close to the current tasting standards. © Verre et Cristal Gilbert Pautot

True for all wines, this principle applies to champagne too. As a white wine with more delicate aromas, the bowl of a champagne glass should be narrower than that of a red wine glass. If proper champagne glasses are unavailable, a white wine glass can be an excellent alternative.

There are many reasons why you may open a bottle of champagne. In the end, depending on the quality of the champagne, what is celebrated, and the number of guests, having different models of champagne glasses at your disposal could be quite the trick. Cheers to that!

Profile and face view of the smiling angel champagne glass in pressed crystal glass created in 1948 by Marc Lalique. © Alexia Say