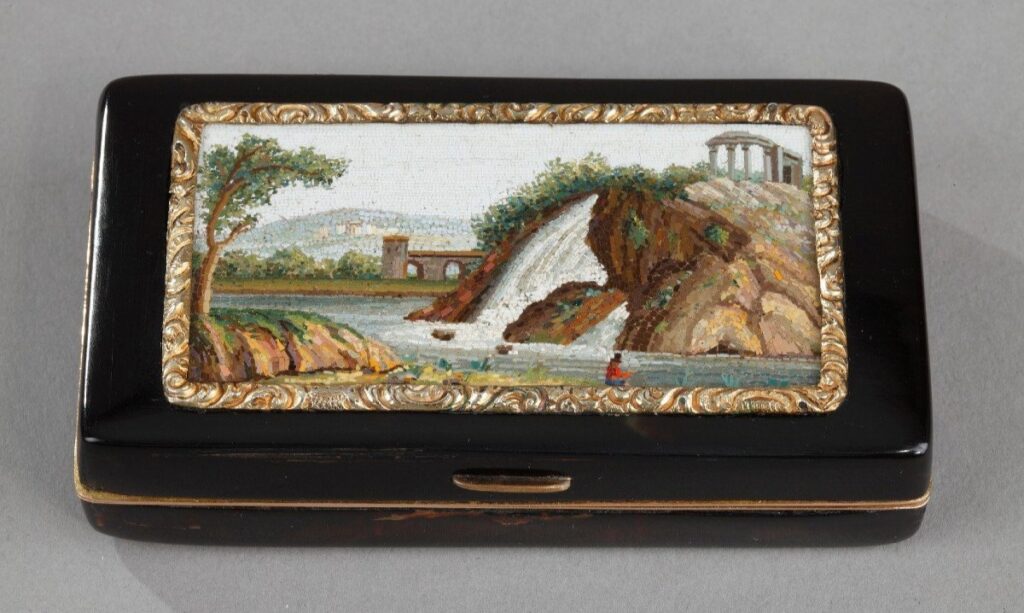

We *had* to begin our article on micromosaics with this splendid snuffbox, featuring two mosaics attributed to Giacomo Raffaelli (1753–1836)—a pioneering master and one of the most renowned figures in the art.

The doves of Pliny are the most emblematic mosaic subject. The Egyptian porphyry, highly prized by Ancient Romans, is a tasteful choice to highlight it.

The two sides of a snuff box in porphyry (7.8 cm in diameter) are decorated with micromosaics by Giacomo Raffaelli: one is the Doves of Pliny and the other is a butterfly. © Belle Histoire

We are thoroughly covering Raffaelli and the Capitoline doves further down among other mosaicists and motifs. But we will first introduce you to the micromosaic technique.

Tesserae mosaic (opus tessellatum in Latin) is an ancient art dating from the third century BCE. Micromosaic, made with minuscule tesserae (fragments of colored enamel or glass called, smalti filati in Italian), is far more recent as it flourished at the end of the 18th century while the Grand Tour was in full swing.

Smalti Falti, or The Minute Art of Tesserae

A micro-mosaic (originally called mosaico minuto in Italian) comprises sections of colored enamels (smalti) stretched during fusion in thin threads (filati). The sections are vertically stacked on metallic trays (brass or gold, mostly) or black Belgian marble backgrounds to compose the desired scenes. Sometimes small fragments of pietre dure are included.

St. Peter’s Basilica, depicted here in micro-mosaics (4.5 cm dia.), is the public epicenter of the Vatican City. The Vatican Mosaic Studio was opened in 1727 specifically to serve this basilica. © Isabelle Marc

To attach the cut pulled-glass rods to the glued support, the mosaicist must use tweezers. Many of these elements have a cross-section smaller than 0.1 cm (0.3 cm for the border threads)… Barely thicker than a hair, these smalti filati can number over 800 per square centimeter! The greater their number, the higher the quality of the object.

They were mostly created in two locations: Rome and Venise. The Roman production generally shows regular tesserae whereas micromosaics from Venise show a larger variety of piece shapes. Moreover, the Roman technique involves waxing and polishing the pieces after assembly and gluing, unlike the Venetian pieces.

Detail from a late 19th-century Venitian micromosaic on a black Belgian marble plaque. The irregularity of the tesserae gives it a completely different charm. © Adele de Luca

Giacomo Raffaelli (1753-1836), Roman Mosaicist, and Other Artists

Giacomo Raffaelli is recognized as the first maestro of micromosaics, alongside Cesare Aguatti. Since the mid-17th century, his family had supplied glass paste to the Vatican Mosaic Studio—even before the organization bore that name. On the Vatican Mosaic Studio’s official website, Raffaelli and Aguatti were the artists who fully revealed the potential of a technique developed by Marcello Provenzale in the early 17th century.

This dog in micromosaics (6 cm dia.) boasts the distinctive style of Giacomo Raffaelli with predominant white tesserae, square ones for the background, and rectilinear ones to outline the main motifs. However, the artworks are rarely signed (or the signature may be hidden). © Ouaiss Antiquités Galerie des Arts

Raffaelli had his Roman workshop and store in the Villa Medici and Piazza di Spagna close vicinity, an ideal location for hosting the Grand Tourists. He may have held the first exhibit on micromosaic in 1775. The commissions by Pope Pie VII, King Stanislas II of Poland, or Napoleon I are the most tangible proofs of his stature in the field.

A detail of an extraordinary “mega” micro-mosaic: Napoleon commissioned Giacomo Raffaelli to create a full-scale reproduction of the Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci. This is exceptional in size: 9.18 meters in width and 4.47 meters in height. The colors and level of detail, especially compared to the original, are stunning. It is visible in Vienna’s Minoritenkirche. (CC from Wikipedia)

Many renowned mosaicists have left their mark on the craft, often working for the papal mosaic studio. Micromosaic also served as a lucrative side activity for many artists. Because signatures were typically applied to the back of artworks, they are often hidden in the final pieces.

Successful workshops employed many craftsmen. Outside of Raffaelli, the Aguatti and Barberi families stood out for several generations in this tradition. Here, we highlight some other names deserving particular attention in the world of micromosaics: Castellini, Ciuli, Luchini, Moglia, Podio, Puglieschi, Salandri, and Savini.

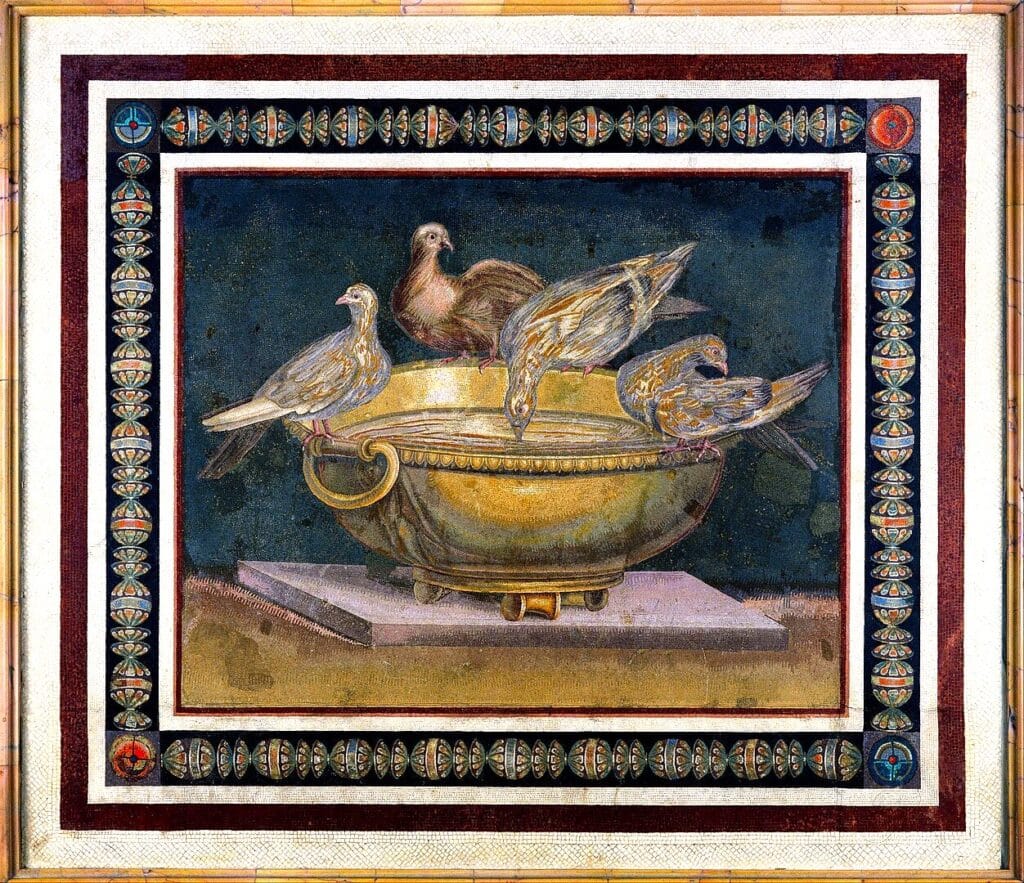

The Doves of Pliny (or Capitoline Doves) and Antiquity

The mosaic found in the Villa of Hadrian refers to Pliny the Elder who wrote about the original of this mosaic (made by Sosus of Pergamon) as the highest excellence attained in this art. Musei Capitolini (Public Domain)

In 1737, the discovery of an ancient wall mosaic depicting four doves perched on the edge of a water bowl at Hadrian’s villa in Tivoli outside of Rome had a resounding effect on the public for a combination of reasons: its astounding conservation state, the aesthetics and size (nearly one square meter), and its inspiration from “Natural History” by Pliny the Elder, the Roman antiquity classic work. The mosaic was quickly transferred to the Capitoline Museum (established in 1734), making it more easily accessible to tourists.

A micromosaic representing the Temple of Vesta and St. Martin’s bridge in Tivoli, near the Villa of Emperor Hadrian. The gold hallmarks correspond to a 1798-1809 period. © Ouaiss Antiquités Galerie des Arts

The Capitoline doves became one of the most iconic subjects for micromosaics. They were copied by Raffaelli and other mosaicists as antiquity was by far the largest source of inspiration for these artists. Neoclassicism progressively rose in the mid-18th century, drawing its aesthetic ideals from the art and principles of antiquity.

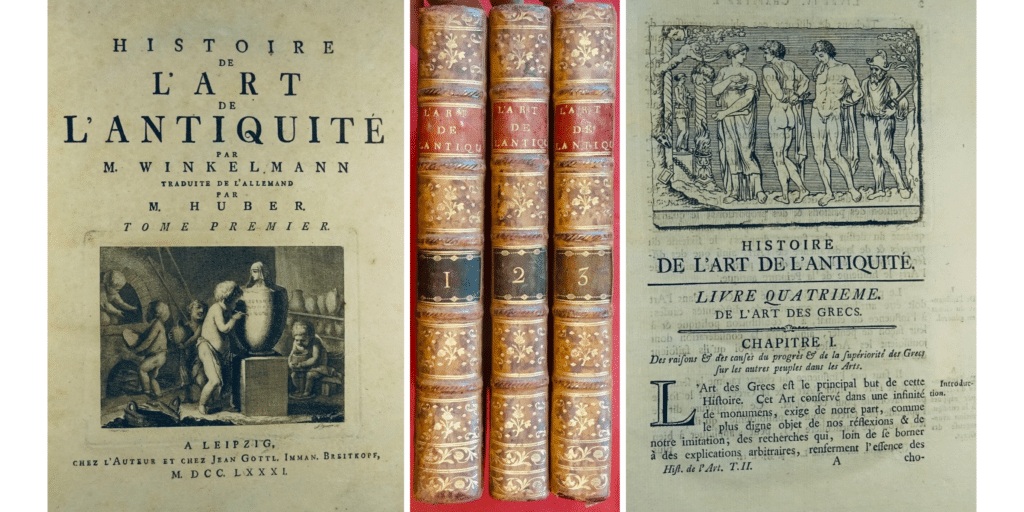

The three volumes in French of “The Art History of Antiquity” by Johann Joachim Winckelmann in a 1782 publication. With full binding in period speckled calfskin. © Librairie Alphabets

The Western World was fascinated by the findings in the archaeological sites of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748). Johann Joachim Winckelmann advocated a return to antiquity with immense success in his “History of the Art of Antiquity” (1764). Moreover, during the Enlightenment, the ancient Greeks and Romans embodied rationality, critical thinking, and cardinal virtues; using their art style and symbolism was a tribute to their ideals.

Micro-mosaic Chrismon with alpha and omega mounted on an 18-karat brooch pin. 19th century. 4.8 cm in length and width. © Mesure et Art du Temps

From Neoclassicism to Romanticism

Consistent with these ideas, classical ancient motifs were explored, including those related to early Christianism, especially as Rome was both the center of the Grand Tour and the Vatican cradle. Consequently, many Roman monuments, classical ruins, and pastoral landscapes were depicted.

An early 19th-century shepherd and his dog in micromosaic (5 x 3 cm). The trend of using the pastoral and folksy characters of Bartolomeo Pinelli (1781-1835) was started by Gioacchino Barberi (1783-1857). © Ouaiss Antiquités Galerie des Arts

Flowers and animals (especially birds, butterflies, and dogs) were successful as well, as were reproductions of famous portraits or paintings. Dogs symbolizing faithful love became very popular with the advent of Romanticism.

The spaniel motif was created by Antonio Aguatti (fl. first half of the 19th century). Both the Aguatti and Barberi workshops mastered malmischiato (the use of several colors in a single glass thread) and enlarged their chromatic scale. The comma and semicircle arrangement of the tesserae, ideal to imitate the dog’s hair, is typical of micromosaics from the 1830s-1840s.

This spaniel after Gioacchino Barberi was made circa 1830. It ornates a paperweight. © Ouaiss Antiquités Galerie des Arts

Rise and Fall of Micromosaics With the Grand Tour

The growth of micromosaics coincided with the popularity of the Grand Tour, peaking in the first half of the 19th century. Rome was a must-see during their journey focused on antique art and culture. Micro-mosaics made the perfect souvenir from Rome and Italy, as both the represented subjects and the craft were descendants of antiquity.

Three men admiring a waterfall in a place resembling Tivoli. They probably are on their Grand Tour. English ink and watercolor, end of 18th century. © Galerie Mazarini

The crème de la crème of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy could bring back or purchase through agents the most exquisite and largest works, as did for instance in 1775 the 9th Earl of Exeter with two panels (roughly 50 cm high) by Cesare Aguatti depicting the Colosseum and the Temple of Vesta.

Most of the time, micro-mosaic is found in smaller sizes. One plaque or more was mounted on many types of objects and jewelry. This versatility made it affordable to more people depending on the quality and the surface size.

Micromosaics Gallery

Jewels

Micromosaics embellish all sorts of jewels. Just name it: earrings, necklaces, bracelets, rings, even buttons, and most often brooch pins.

A jeweler from Rome knew how to leverage micromosaics with unparalleled talent: Castellani opened from 1814 to 1927. This name is synonymous with the finest quality. The Castellanis served Risorgimento, the political concept behind the unification of Italy.

Etruscan revival brooch pin by Carlo Giuliano for Castellani. The gold is crafted into a fine braid and cords surrounding a rosette in micro-mosaic. © Valérie Severac

An Italian pastoral scene in micro-mosaic inspired by Francesco Londonio (1723-1783) mounted in an Etruscan revival gold bracelet reminiscent of Castellani’s work. Circa 1860-1870. © Ouaiss Antiquités Galerie des Arts

Victorian brooch pin with a lying spaniel in micro-mosaic on an onyx background and 18-karat gold setting. LM initials for Luigi Moglia. © Antiquités Joel Trulla

Objects of Vertu and Boxes

The most common objects featuring micromosaic inserts include snuff boxes, bonbonnières, and vinaigrettes—typically crafted from luxurious materials such as gold, silver, or tortoiseshell.

The mosaics were not always brought back as souvenirs. Goldsmiths outside Italy could import them as well to incorporate into their designs, selling them in countries like Great Britain, France, and Germany.

This vinaigrette boasts a magnificent pug micromosaic, probably by Antonio Aguatti’s workshop, and sumptuous goldsmithing by Gabriel Raoul Morel with a rooster gold hallmark indicating a 1798-1809 creation period. © Ouaiss Antiquités Galerie des Arts

An early 19th-century snuffbox with a representation of the Colosseum before its restoration by Pope Pius VII. 1828 London stamp of the goldsmith John Linnit. Gilt silver and 18-karat gold. © Antique and Gallery Mignon

Tables and Gueridons

The most monumental pieces with micromosaics—apart from exceptional fresco- or painting-like works—are tabletops. These are typically crafted in combination with marble and pietre dure, reflecting the rich tradition of ancient Roman artistry.

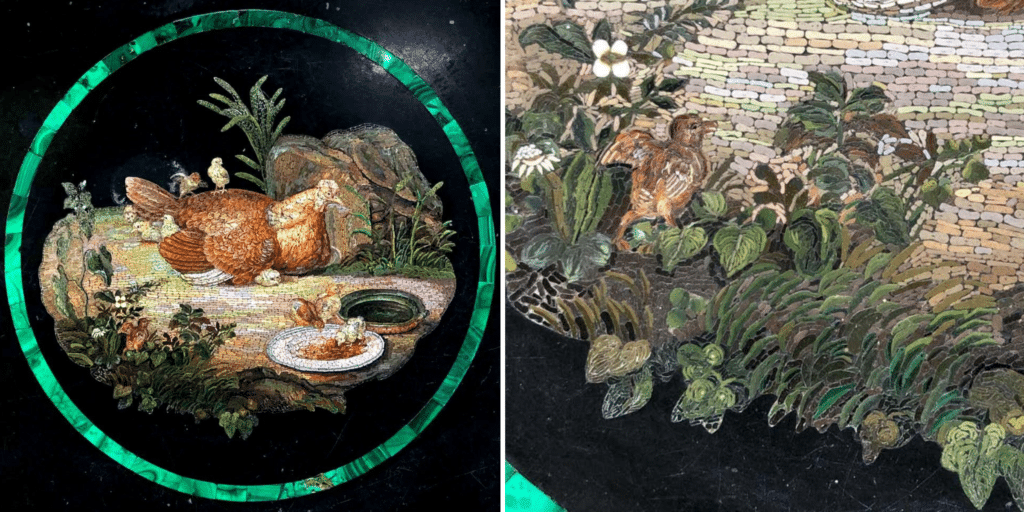

This micro-mosaic centerpiece of a larger marble tabletop is attributed to Gioacchino Barberi after a painting by Johann Wenzel Peter (1745-1829). © Le Brun Antiques & Works of Art

A mahogany gueridon table, probably created by Francesco Sibilio circa 1830: different types of marble, 84 samples of hard stones, antique Roman polychrome glass, and a micromosaic. © Galerie Nicolas Lenté

You May Like

Micromosaic | Mosaic | Grand Tour | Neoclassicism | Rome | Italian Art & Antiques