Banner legend: The LALIQUE dining room during the 1925 Paris exhibition. A picture from “Furniture Sets, 1925 International Exhibition”, 3 in-folio albums by MAURICE E. DUFRENE edited by Charles Moreau. © Alexia Say

*~*~*

2025 is a big year for Art Deco with the 100th anniversary of the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris (April 28 to November 30, 1925)—the official “launch date” of the Art Deco style. Of course, the reality is more complex—as it always is.

Indeed, let us celebrate Art Deco, an iconic art style deployed roughly from 1910 to 1940. We should not spoil the pleasure of celebrating something. But isn’t there even more to celebrate with this anniversary of the 1925 exhibition?

Art Deco blossomed at the 1925 Decorative Arts Exhibition in Paris. This versatile style also had something to say about gardens. Here, a golden yellow stencil on green paper by Paul Véra accompanying prints from “The Gardens”, a 1919 book by André Véra illustrated by his brother Paul Véra. The two brothers collaborated with the “Compagnie des arts français” and were essential to bringing cubism into applied arts. © Blanès

Consider that we went from “1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts” to “Art Deco”—short for art décoratif, coined only in 1966 during a major tribute exhibition in Paris about this style. Today, we tend to drop everything outside the decorative arts aspect, but what if the whole name encapsulated something more exciting, the plurality of the arts in 1925?

This is why you are now invited to a thorough and instructive breakdown of what “1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts” truly tells us about Art Deco AND Modernism. Let’s now enter the subject through the grand gate!

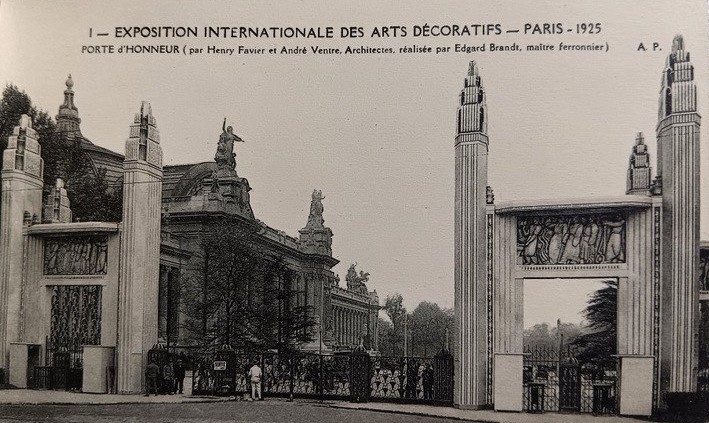

The Honor Gate of the exhibition was architected by Henry Favier and André Ventre. The visitors were welcome through ironworks of Edgard Brandt. Wrought iron was widely showcased during this exhibition and became a staple of Art Deco. © Les Trésors d’Isabelle

Table of Contents

- Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts: Why Modernity is Essential to This Exhibition

- Modernity in 1925

- Artistic Influences on Art Deco and Modernism

- The Decorative Arts at the 1925 Exhibition: The Main Art Deco Artists and Their Works

- Industrial Arts: A Prelude to Modernist Success

- International Exhibition in Paris: France Strives to Lead Arts Again

- Conclusion

Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts: Why Modernity is Essential to This Exhibition

In the term “Art Deco” today, we didn’t keep a major keyword used in the original exhibition name: Modern. You may rightly wonder: what is “modern” in Art Deco compared to “modern” in the previous art movements such as Art Nouveau (after all called “Modern Style” in Great Britain or “Modernisme” in Catalonia)? The importance given to modernity was not new—without even referring to the perpetual quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns.

A good starting point to narrow down the vast question of modernity is to figure out what it meant for the event organizers. This excerpt from the “1931 Rapport Général” (written by the French Ministry of Trade and Industry about the 1925 exhibition) gives a good summary of what modernity encompassed:

To reconnect with tradition through its inherent logic, to find in the purpose of objects and the technical means of their creation a new expression that is neither a contradiction nor an imitation of past forms, but rather their natural continuation—this is the modern ideal of the 20th century.

This ideal is now influenced by a new force: science.

They clearly state that they want a new expression that relates to tradition. They express their desire for continuity. But if we read between the lines, we also understand that “the purpose of objects and the technical means of their creation” (in other words, functionality and production) reshuffle the cards, especially as science is recognized as a major driver. Could it lead to a break with the past?

A remarkable combination of three lamps by Max Le Verrier. Two ‘Lumina’ and one ‘Espana with fan’, the latter designed by Raymonde Guerbe. Max Le Verrier, a talented artist and founder, received a gold medal at the 1925 exhibition. © Metropolis Art 1900

We can discern ongoing debates regarding the balance between continuity and novelty. Indeed, two distinct schools of modernity clashed at this exhibition. One leaned more toward tradition, embracing an official line that captured the spirit of the times and reflected the general opinion in France, characterized by a pronounced decorative or ornamental quality—later known as Art Deco. The other school, in contrast, gravitated toward an industrial or streamlined aesthetic—subsequently referred to as Modernism.

This article uses “decorative” vs. “industrial” to represent this polarization as both adjectives were in the exhibition name. However, “industrial” also meant that manufacturers or brands such as Baccarat, Christofle, Lalique, Sèvres, or department stores had pavilions too (find out more about the Bon Marché pavilion). The presence of these stores at a world fair was new (and modern for that matter).

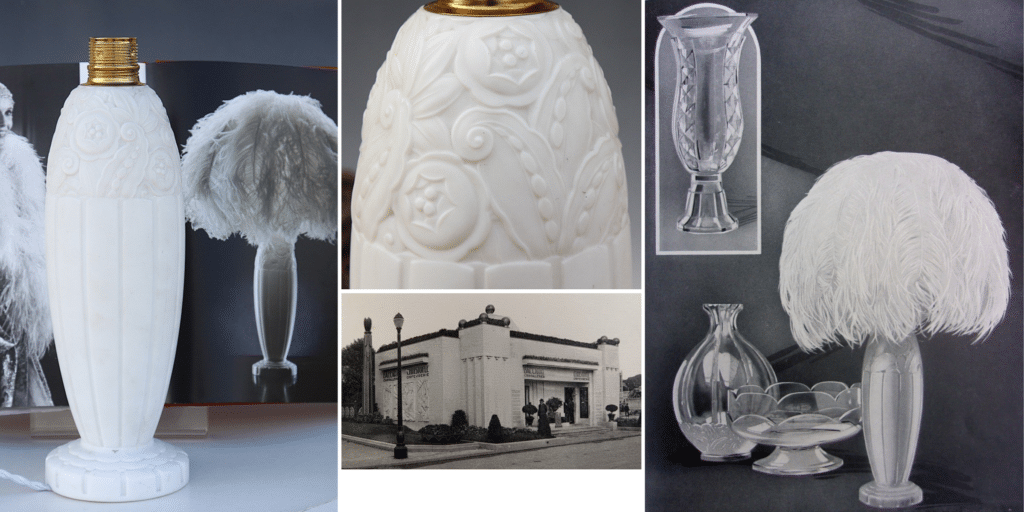

This lamp model in opaline was listed in Baccarat’s catalog for the 1925 exhibition. The fluted leg was inspired by the Louis XVI style, while the original (and missing) feather lampshade was a nod to cabaret dancers. © Antiques20ème

Modernity in 1925

First, it is important to note that the idea of an international decorative arts exhibition in Paris was first proposed in 1907 and gradually developed over time. Originally planned for 1915, it was inevitably postponed due to the First World War. Therefore, the ambition to showcase modern decorative and industrial arts in Paris had been taking shape since the early 20th century.

Science and technology had been the strongest forces driving modernity since the 19th century. However, the arts of that era largely remained rooted in the past. Over time, advancements in electricity, complex machinery, and new materials began reshaping industry, construction, and transportation, becoming increasingly visible in everyday life. By the early 20th century, these innovations were rapidly scaling and transforming society.

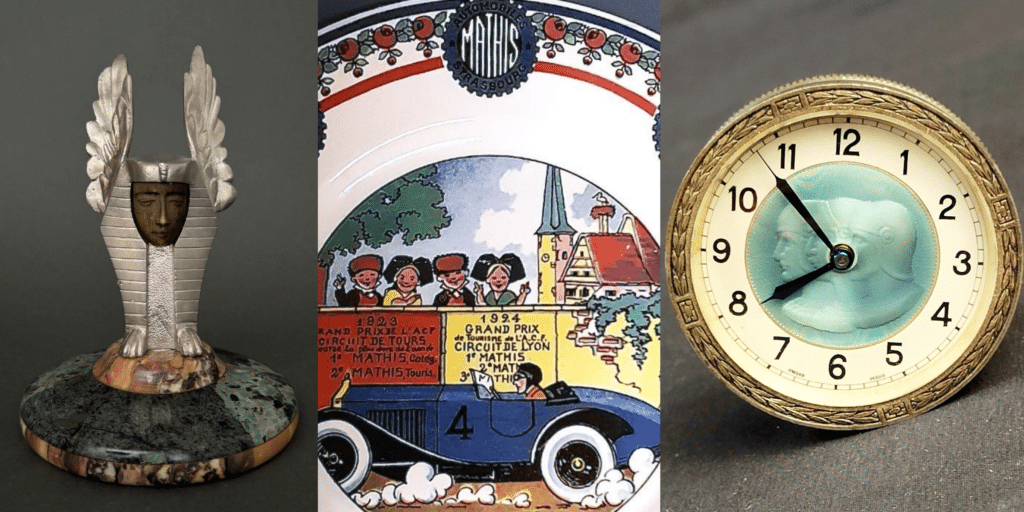

The automobiles and the decorative arts in the 1920s. In the middle (© Alain Benedick), a racing car is the motif of an advertising plate for the Mathis car brand from Strasbourg. Alsace is French again since the end of WWI, a subject of celebration too. The cars also create new needs for their owners. On the left (© Antiquités Caignard), a winged sphinx car mascot inspired by the discovery of the Tutankhamun tomb in 1922. On the right (© O Passé Composé), a Swiss-made car clock in a typical neoclassical Art Deco.

These changes were also transforming homes, which is our primary focus with decorative arts. Lighting, of course, played a key role, but radios were also beginning to find their place in daily life. With running water becoming more widely available, working-class households increasingly gained access to indoor toilets or bathrooms. The devastation of the Great War, despite its tragedy, created an opportunity to rebuild with these modern innovations in mind.

People were able to go to dedicated movie theaters. Aviation turned heads during air meets, and crossing records made the headlines. Trains, cars, and ocean liners were accelerating imports and cultural exchanges.

Two daring aviatrices in the 1920s. Lilly Dillenz Hollitzer on the right and Maryse Bastié on the left. She did her first solo flight in 1925 and later set several women’s world flight records. She was also a French suffragette. © Antiquités Garnier

Societal changes also fueled the search for new artistic expressions. Cultural influences from across the globe—e.g. jazz, the Ballets Russes, tribal art, and ancient Egyptian aesthetics—were eagerly embraced. The Roaring Twenties earned their name through the excitement of newfound possibilities and the belief that past norms could be successfully challenged. The aftermath of World War I, the collapse of empires, and the rise of communism further accelerated the emancipation of women and sparked identity searches or claims among some peoples.

Thus, 1925 was a year full of potential. The new ideas and arts that had emerged since the beginning of the 20th century—Art Deco and Modernism were not born in 1925—had had some time to mature. The European countries recovered from the First World War were ready for new adventures.

Artistic Influences on Art Deco and Modernism

The Applied Arts Reaching Their Peak

The late 19th century to the Second World War was a golden age for applied arts as industrialization and machines constantly pushed people to redefine how to combine aesthetics, functionality, and production. In France, many changes happened over a short time to organize applied arts, primarily for commercial purposes.

In 1863 the Union Centrale des Beaux-Arts appliqués à l’Industrie (Central Union of Fine Arts Applied to Industry) was created and became the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs (Central Union of Decorative Arts) in 1882. The magazine Art & Décoration was born in 1897 to reach the general public.

Signed poster project by Robert Bonfils for the “Société des Artistes Décorateurs” in 1923. Chinese ink and gouache on tracing paper. Later, Bonfils created one of the iconic posters of the 1925 Exposition. © Thierry Neveux

Finally, the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists), or SAD for short, was created in 1901—it held a key role in organizing exhibitions promoting modern decorative arts after the controverted 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris. The founding members such as René Guilleré, Paul Follot, Maurice Dufrêne, or Edmond Lachenal were key contributors to the development of Art Deco (after having evolved in Art Nouveau).

A Complicated Relation With Art Nouveau

Art Deco’s relationship with Art Nouveau—the key artistic movement that precedes it—is ambivalent. Certainly, art nouveau was harshly criticized for its tendency towards convoluted forms; some did not refrain from mocking the “noodle style”.

However, Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts were also a source of inspiration, sometimes for the quality or luxury of their production, sometimes for the underlying social ideas, or because they dared to be disruptive in a 19th century prone to rehash past styles. The designs of the Wiener Werkstätte led by Josef Hoffmann contributed to Art Deco, even though it was an evolution of Sezessionsstil, the Austrian Art Nouveau.

The Wiener Wekstätte team was involved The Fledermaus line was originally created by Josef Hoffmann for the opening of the Cabaret Fledermaus in 1907. © Galerie des Minimes

Found in both the decorative and industrial branches of the exhibition, the concept of ‘total work of art’ (Gesamtkunstwerk), also present in Art Nouveau and even some older European art traditions, emphasized a cohesive work on architecture, interior design, furniture, fine arts, and the gardens as well.

Infused With the Visual Arts of the Early 20th Century

Visual arts influenced Art Deco and Modernism as well. Particularly after 1905, arts were like an open-air laboratory with limitless experimentation on colors and shapes. In France, the impact of fauvism and cubism on Art Deco is the most obvious, as well as tribal arts, especially from Africa and America. The simplification of volumes and colors is core and center to these movements.

The cubist inspiration in architecture and decorative arts quickly became tangible when Raymond Duchamp-Villon, André Mare and Albert Gleizes (among others) presented “The Cubist House” at the 1912 Fall Salon in Paris.

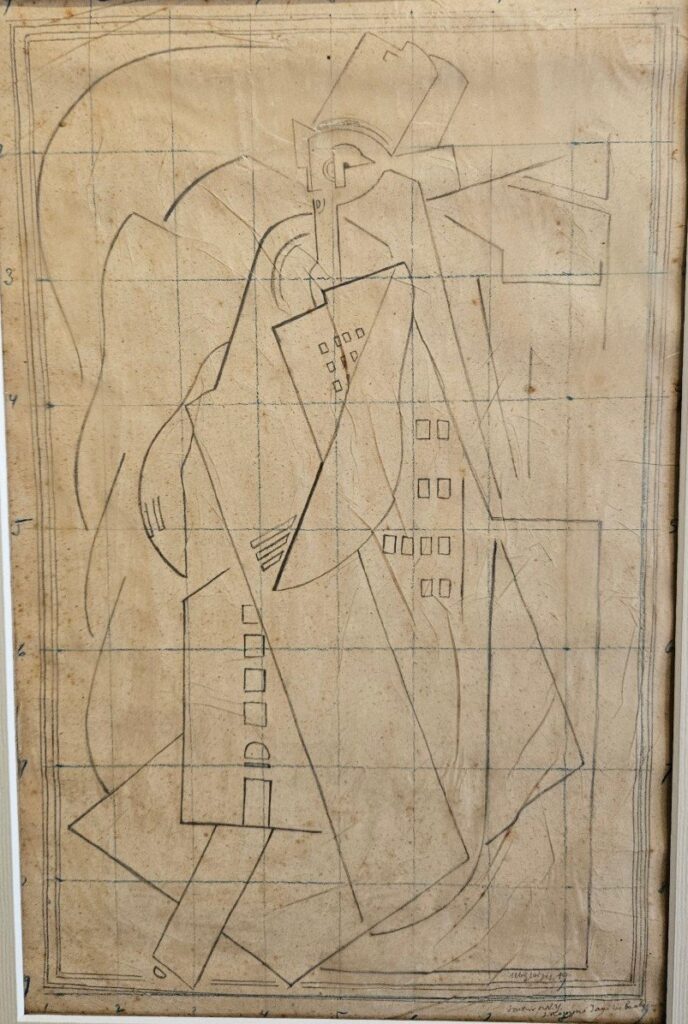

Drawing on tracing paper signed and annotated by Albert Gleizes in 1919: Memory from New York, The man in the buildings. Gleizes published “Du Cubisme” with Metzinger in 1912. He lived in New York in 1915-1916. © Galerie Guardia

Suprematism, constructivism, futurism, and neoplasticism—all abstract art—also played their part, especially on the more industrialist side (Bauhaus and De Stijl). The fine line between geometrization and abstraction was crossed.

The modernity of their utterly novel approach was reinforced by the modernity of their subjects when they represented movement or speed (e.g. futurism) and leveraged mechanical or industrial shapes (e.g. purism, constructivism).

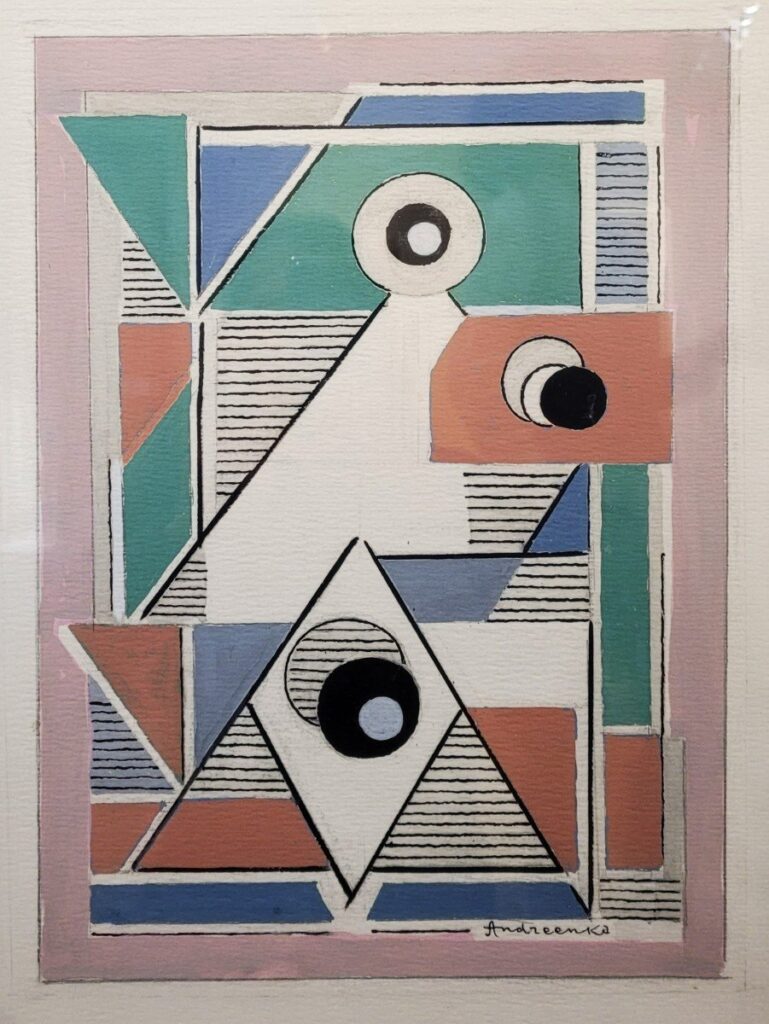

A Constructivist Composition by Michel Andreenko (1894-1982) around 1925. Born in Ukraine, he studied in Russia, and moved to France in 1923. © Galerie Portalis Aix

The Decorative Arts at the 1925 Exhibition: The Main Art Deco Artists and Their Works

Art Deco Key Facts: Stylized ornaments, geometry, luxury, references to historic styles, craftsmanship.

In 1925, the Art Deco style is given a clear and succinct definition in the exhibition guide—in the section developing why the exhibition came to be and its objective:

Today’s style [what we now call Art Deco] seeks beauty in simplicity and luxury in the quality of the material.

Simplicity and luxury are the two keywords to remember. This style dominated the exhibition and is representative of the Art Deco as we know it today across the world. Most of the 150 pavilions and temporary buildings were in this vein.

A bar cabinet attributed to Jacques Adnet, entirely sheathed in shagreen with a gilt base. Interior in maple veneer. Adnet was working for Dufrène at La Maîtrise for the 1925 exposition and showcased ceramics. © GALERIE XXeme

Elements of the Art Deco Style

Simplification incarnated simplicity. Simplification essentially involved two key aspects: a focus on basic volumes (through the elimination of details) and the geometrization of forms. Ornaments being an integral part of the French decorative arts tradition, simplification didn’t mean eradicating ornamentation. There was no intention of renouncing figurative art too.

“Flowers”, a gouache by Raoul Dufy for Bianchini-Férier. Dufy worked for the luxury silk manufacturer from 1912 to 1928. © Villa Rosemaine

Remember the connection to the artistic tradition we mentioned earlier. Neoclassicism (particularly the Louis XVI, Empire, and Restauration styles) was a favored source of inspiration for some decorators, evident in both lines and motifs. Floral elements—especially roses—along with fruits, were ever-present. Animals, too, could brighten up surfaces, ranging from European classic specimens to exotic wild creatures and birds or inhabitants of the aquatic world.

Contrasting colors were favored. Metallic accents or parts (gold, silver, bronze, chromium-plated steel) were often included for their luxurious or modern aspect. For furniture, sumptuous and exotic woods were in the spotlight (Macassar ebony, amboyna, kingwood, rosewood, mahogany, thuya…). They were used primarily for unadorned surfaces. Inlays were rare—especially compared to Art Nouveau—though some designs featured wood combined with precious materials such as ivory, shagreen, parchment, or mother-of-pearl. Lacquer and glossy varnish emphasized the exotic and expensive look.

Details make the difference for playful contrasts of shapes, colors, and materials. Top: Rosewood wardrobe with mahogany carving attributed to Auguste Vallin (© Breton). Middle: Table in Macassar ebony with curule strip base (© Galerie Atena). Bottom: Sideboard by Lévitan with black piano lacquer, cream parchment, and chromium-platted fittings (© Coloneum Antik).

With Art Deco, space was also given to vernacular arts. For instance, French regions (such as Provence, Alsace, and Normandy) or cities (like Lyon, Limoges, Mulhouse, and Nancy) had pavilions at the exhibition. Art Deco is versatile as no ideology imposes limits and figuration is accepted: geometrization can be applied to any motif including regional ones.

The Most Successful French Art Deco Designers

The prominent French furniture, interior designers, and craftsmen in Art Deco were members of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (mentioned earlier) and its associated Salon.

Remember Their Names

It comes as no surprise that certain artists who shaped Art Deco stand out. If only one was to be remembered, it would be Jacques Émile Ruhlmann. He established a sort of gold standard in this style. Ruhlmann epitomizes a highly refined, utterly luxurious Art Deco meant for the elite.

Pedestal table, model “Elegant” by Jacques Emile Ruhlmann. Can you spot it in the boudoir of the Hôtel du Collectionneur at the 1925 exhibition? The one on the right has an exceptional provenance: from the family of Maurice Pré, the carpenter who worked for Ruhlmann from 1924 until the designer’s death. © Galerie Tramway

Jean Dunand is particularly known for his lavish lacquers applied to objects and furniture. He was also a sculptor, and jewelry designer, and his love for metalwork led him to master dinanderie (copper and brass metalwork). Like many Art Deco artists, he was a jack-of-all-trades in interior design.

Many leading Art Deco artists embraced this multidisciplinary approach, influenced by the concept of total art, which fostered the development of the ensemblier-décorateur role. While any list inevitably omits deserving names, the following key figures will serve as a great starting point for further exploration: Louis Süe & André Mare (founders of the “Compagnie des Arts Français” in 1919 with the motto “Evolution within tradition”), André Groult, Paul Follot (head of the Pomone art studio by Le Bon Marché), Maurice Dufrène (head of La Maîtrise art studio by the Galeries Lafayette), Jules-Émile Leleu.

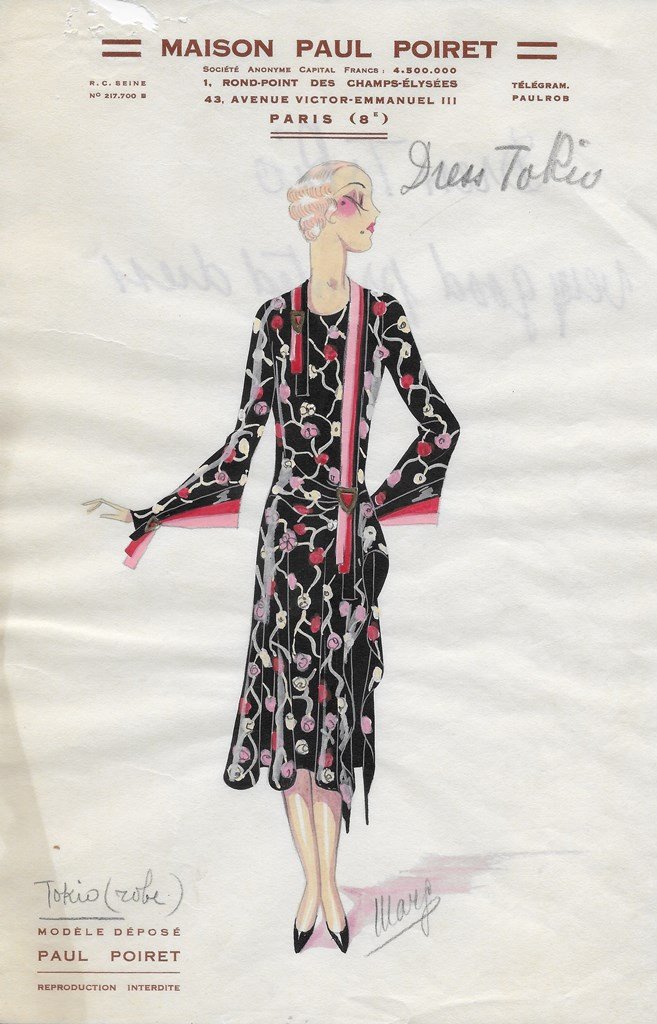

Some Art Deco artists specialized in a craft. For instance, Jean Puiforcat in silversmithing, René Lalique for glasswork, Edgar Brandt and Raymond Subes for ironwork, Claudius Linossier in coppersmithing, and Paul Poiret in fashion.

Sketch of a Paul Poiret printed dress, model “Tokio”. Considering the address in the letterhead, it was designed between 1925 and 1929. © Thierry Neveux

Some Outstanding Creations at the 1925 Exhibition

Some specific pavilions or displays made a strong impression. The Hôtel du collectionneur (the collector’s mansion) developed by the Groupe Ruhlmann was all-around stunning, certainly the most luxurious. The Ambassade française (a French embassy) was the official place to promote ensembles created by designers of the SAD—the fully lacquered smoking room by Jean Dunand delivered a striking wow factor.

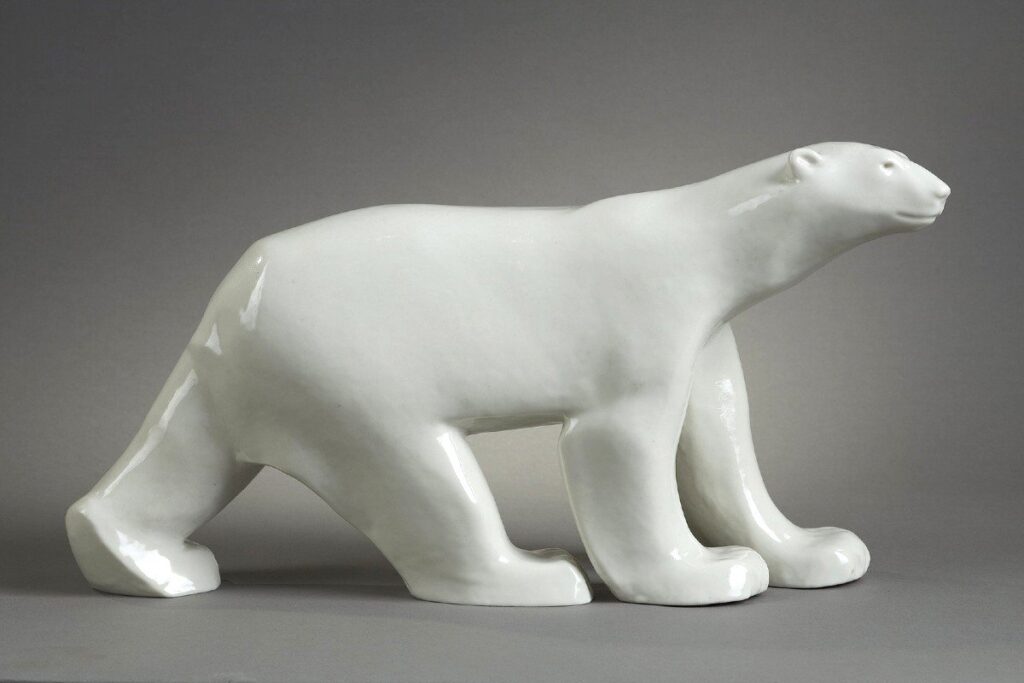

Polar bear walking by François Pompon. Sèvres edition in enameled biscuit dated 1927. Similar bears by Pompon were present at the exhibition. One at the Hôtel du Collectionneur in bronze, another at the Ambassade Française in stone. © Galerie Tourbillon

Lalique was one of the biggest stars of the show. In addition to having his own pavilion, he contributed to others and, most notably, created one of the exhibition’s standout attractions: a 15-meter glass fountain, illuminated at night by what many still called “the Fairy of Electricity,” as they had yet to experience it at home.

Statuette and catchall by René Lalique belonging to the Clos Sainte Odile line created in 1925. Inspired by the caryatids used in his monumental fountain during the exhibition. © BG Arts

However, some artists and art critics felt that designers of the “decorative” trend were too bound by outdated, overly ornate artistic conventions and failed to consider the average person’s practical needs and financial means.

Industrial Arts: A Prelude to Modernist Success

Modernism Key Facts: Minimalism, affordable (social vision), abstraction, utilitarianism, universalism.

As said earlier, we oppose the “decorative” to the “industrial” trends to illustrate some fundamental differences in vision. However, the boundary between the two movements remained fluid, varying by designer.

Someone like Eileen Gray (she was not exhibiting in 1925), evolved from a more ostentatious Art Deco style (as a renowned lacquer specialist) to modernist creations with a strong influence of De Stijl and the Bauhaus, among others.

Eileen Gray designed this transat chair in 1927 for the Villa E-1027. 90s edition in black leather and lacquer by Ecart International. © BG Arts

The Absence of the Bauhaus and De Stijl

De Stijl and the Bauhaus, these two heavyweights of Modernism, were not at the exhibition for different reasons.

Germany was still an outcast for France after the First World War. As such Germany was not invited and the Bauhaus had no chance to be represented. 1925 was in fact a turning point and the French boycott of German artists stopped in 1926.

The B3 chair was designed by Marcel Breuer while at the Bauhaus. This is his first tubular metal furniture. This model is also known as ‘Wassily’ as he created it for his colleague and friend Wassily Kandinsky. © Sarazin – Cabinet de Curiosités

On the other hand, the Netherlands had a pavilion, but their own country left out De Stijl for more traditional artists. No man’s a prophet in his own country, could we say. It is no mystery that when you’re avant-garde you promote ideas not yet accepted by the mainstream.

Compared to the more traditional Art Deco, there is a major conceptual, even utopian, component to Modernism. Historically, De Stijl influenced the Bauhaus. Here is a way to synthesize the main and common principles of De Stijl and the Bauhaus:

Total abstraction (with a preference for pure colors and straight lines) can unite mankind. In an era of machines, abstraction should empower the arts (hence the importance of geometry) and be associated with industrial processes to improve the lives of humans all over the world. The corollary is that this collaboration with industry should make it possible to mass-produce tasteful housing and objects affordable for everyone.

The Modernists at the 1925 Exposition

The ultramodern wing was under-represented at the exhibition. The most remarkable figures were Auguste Perret, Le Corbusier, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Konstantin Melnikov, Pierre Chareau, and Francis Jourdain. Most of them were architects, able to envision and create entirely new types of spaces, complete with furnishings and decor.

Auguste Perret, an early pioneer of reinforced concrete with a daring “Style Without Ornament” manifest, was already a well-established architect in 1925. The architect who said “Where there is true art, there is no need for decoration” was appointed to the building of the temporary theater. Perret conceived it to serve the needs of modern theater with bold stage action and blocking.

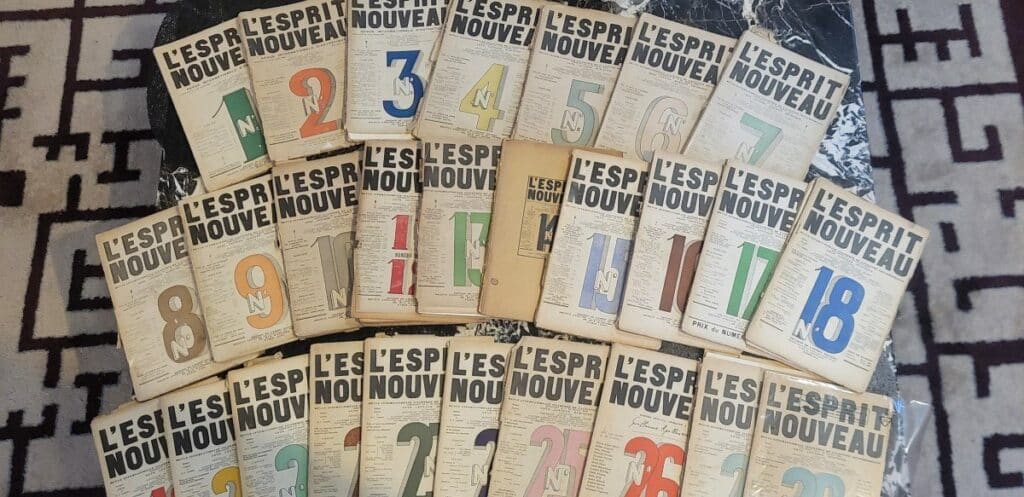

Le Corbusier reused the name of a journal for his pavilion at the 1925 exhibition. This “International Journal of Aesthetics” was created by Le Corbusier and Ozenfant. It expanded on the principles of Purism, exploring their aesthetics and manifestations across all art forms, from architecture to literature. You can see here the whole collection, 28 volumes, of the L’Esprit Nouveau from 1920 to 1925. © Delmas Horlogerie

Le Corbusier, who worked for Auguste Perret around 1908–1909, sparked the most controversy at the exhibition with the L’Esprit Nouveau pavilion. Collaborating with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret and Ozenfant, he aimed to define the ideal modern apartment. His vision centered on a modular storage system to reduce the need for furniture and a layout designed for functionality. It was not about crafting a luxurious home for the elite—true comfort, in his view, lay in light, space, and practicality. Many found it disturbingly ugly, including Charles Plumet, the exhibition’s chief architect, who went to great lengths to conceal it behind a palisade—removed only after a minister intervened.

When the exhibition began, Robert Mallet-Stevens was completing the first phase of the Villa Noailles’ construction in Hyères. At that time he was still an up-and-coming architect, better known as a designer. In the Ambassade française, his streamlined hall clearly stood out from a more ornate pavilion (as did the smoking room and library by Pierre Chareau and the gym by Francis Jourdain). The monumental panel by Robert Delaunay with a naked woman in front of the Eiffel Tower crowned by luminous circles was a bold depiction of bustling urban life with a thoroughly modern elegance.

The Pavilion of Information and Tourism by Robert Mallet-Stevens. Drawing and gouache. CC 2.0 Dalbera

Mallet-Stevens also architected the Pavilion of Information and Tourism. His 35-meter clock tower only decorated by a set of orthogonal or parallel plans had a grace that pleased many, including the architect of the soviet pavilion, the constructivist architect, Konstantin Melnikov. The USSR pavilion made of two triangles with façades where glass dominated was considered the most avant-garde building.

Paving the Way to the UAM (Union des Artistes Modernes)

The exhibition clearly showed a growing gap between the most traditional and modern artists of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (SAD). The break was complete in 1929 when the SAD refused to allocate a shared exhibition space for the modern group in their annual salon.

As a result, the Union des Artistes Modernes (UAM) was created in May 1929. The founding members were Robert Mallet-Stevens, Raymond Templier, Charlotte Perriand, Hélène Henry, René Herbst, Francis Jourdain, Jean Puiforcat, Jacques Le Chevallier, and Jean Fouquet. They were soon joined by Le Corbusier, Fernand Léger, Jean Prouvé, Eileen Gray, Sonia Delaunay, Jean Carlu, and Pierre Chareau.

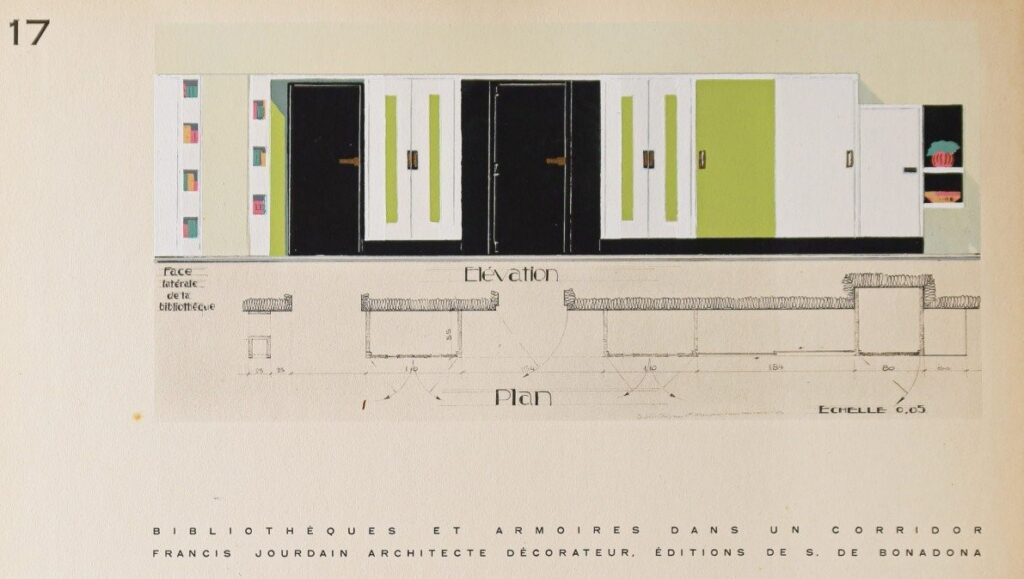

Design by Francis Jourdain, architect-decorator, in 1930: cabinets and shelves in a corridor. Original gouache stencil. © Patrick Serouge

Their 1934 manifesto claimed that “Modern art is truly social—pure art, accessible to all, and not an imitation made for the vanity of a few“. They reinvented furniture shapes using breakthrough materials adapted to industrial production. Yet, there is an undeniable paradox: despite their original social objective, their creations remained largely elitist and expensive. Jean Prouvé and Jean Carlu were among the few who stayed most true to the commitment to affordability.

International Exhibition in Paris: France Strives to Lead Arts Again

Twenty-one countries outside France participated in this exhibition. The USA and Germany were the most notable absent players. The French colonies also had their own separate pavilion or spaces.

The French and international visitors could enjoy the diversity of foreign crafts and their latest creations. For Sweden, Carl Malmsten for the furniture or Orrefors glass (one of the artistic directors, Hald, was a pupil of Matisse) stood out as did the Wiener Werkstätte for Austria.

However, the international scale served the host country, France, first and foremost, which was the organizers’ objective. Indeed, other European countries such as Great Britain, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Italy (with the 1902 exhibition in Turin) had caught the modernity train earlier. France needed to restore the prestige of its artistic excellence.

The French Embassy name for the SAD pavilion was no coincidence. Indeed, France had true ambitions for export. The exhibition served as a successful showcase to captivate foreign audiences with the Art Deco style (hence the French name that remained associated with the style for posterity), as shaped by the French artists who made a strong impression during the event.

Claudius Linossier, a student of Jean Dunand, took dinanderie to its finest. Present at the 1925 exposition, he had won the Blumenthal grant in 1922, a prize from the “American Foundation for French Art and Thought”. This opened the American market to his creations. © Antiquités Robert Gaillard

For instance, Prince Aska Yasuhito and Princess Fumi Nobuko of Japan, in need of a new palace after the 1923 earthquake, were so impressed by the exhibition that they decided to embrace Art Deco for their new residence—completed in 1933 and now home to the Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum. For the interiors, they involved Henri Rapin and René Lalique (met at the exhibition) as well as Léon Blanchot, Raymond Subes, and Max Ingrand.

The USA did not have any pavilion, but American journalists and major delegates from corporations related to decorative arts came to observe. In 1926, Charles Richards, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized a traveling exhibition in Boston and New York City with works of Ruhlmann, Dunand, Lalique, and Süe / Mare. This brought the style onto the American stage, leaving its mark on the era through skyscrapers that redefined the cityscape and cinema, which showcased these innovative designs on the screen.

In 1925, Christofle was the world’s leading silversmith by revenue. It didn’t stop the company from being innovative. The new designers Christian Fjerdingstadt and Luc Lanel impressed by their modernity and the vibrant purity of the lines in their creations. This swan sauceboat by Fjerdingstadt was presented in 1925 and manufactured by Gallia (a Christofle brand) in 1935. Christofle continued to expand, later supplying modern modes of transportation, including the Orient Express, the Normandie ocean liner, and Air Union (Air France). © Barrois Antiques

Conclusion

The 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts crowned a style called Art Deco in 1966. The simplification of lines, essential to the expression of modernity, was built upon the deep foundations of the French and European ornamental tradition.

However, Modernism, with its sharp sense of function and relentless drive for boundless experimentation with shapes and materials, planted strong seeds that matured slowly but steadily.

These two artistic movements coexisted and despite some dogmatic debates influenced each other. Art Deco evolved. In particular, the metal tube, so predominant in Modernism, inevitably influenced Art Deco, leading to an increasing use of chrome. Moreover, the circle-straight line contrast and smooth, unadorned surfaces accentuated over the 1930s with the emergence of Streamline Moderne (or ocean liner style).

The 1929 economic crisis and Second World War weighted hard on the luxurious facet of Art Deco. Tubular steel, plywood, and fiberglass (and then plastic) were far more appropriate to the challenges of mass production and standardization of the post-war: Modernism took over.

####