A close observation of this pair of polychrome wax reliefs by Caspar Bernhard Hardy (German, 1726-1819) is a wonderful opportunity to rediscover wax modeling. Wax portraiture in Europe was appreciated by both the people, who could enjoy wax sculptures in public places such as churches or galleries, and the rulers—patronizing wax artists for their private collections or public displays.

Fruit and vegetable sellers by Caspar Bernhard Hardy. A pair of wax reliefs. © Le Brun Antiques & Works of Art

A Pair of Wax reliefs: Sellers of Fruits and Vegetables

Wax fruits detail. Note the glass insert for the grapes. © Le Brun Antiques & Works of Art

In these wax reliefs, our attention instantly focuses on what this woman and man are clearly showing us. That is, the fruits and vegetables, so true to life in the foreground of these frames. The woman is holding in her apron what you need to cook a heartwarming stew: cabbages, turnips, and a carrot. The man shows up on a slab some appetizing autumn fruits: grapes, pears, quinces, and apples. These high reliefs were made around 1800. Yet, the characters look as if they could push the glass in front of them and jump out of the gilt frames.

Several elements contribute to the realism of these scenes in wax. High reliefs, by nature, give more space to details and light than low reliefs. Thanks to its malleability, wax modeling can be remarkably precise. The translucence of the material is also ideal for representing skin and flesh and providing accurate likeness to humans. Moreover, wax colors stay fresh and vivid when properly preserved. Here, the greens, blues and pinks contrast nicely against the beige and grey tones.

Vegetable seller in wax. Note the fabric addition at the edge of her sleeves. © Le Brun Antiques & Works of Art

The hair and clothing particularly strike us with realism. The clothing creases underline the characters’ moves. The hairlocks form nice waves. The roses in the woman’s hairdo look as if just plucked from the garden. The intricate details of the clothing, from the ribbons on the sleeves and the patterned corset, to the buttons and stripes on the man’s waistcoat, help us appreciate the fashion of the late 18th century.

Despite all the singularities of these characters, with these reliefs, the objective is not to represent one person in particular. Hardy represents types of people or social groups. Thus, he can create generic faces. We can see similarities with other reliefs created by the artist. For instance, the vegetable-selling woman is reminiscent of the Lady with a mirror at The Met. Indeed, Hardy created molds he would reuse several times for the basis of his characters. When he was unmolding, and the wax was still warm, he could customize his work with the desired details and colors.

Lady With a Mirror by Caspar Bernhard Hardy at The Met. Public Domain.

Caspar Hardy’s Wax Reliefs: Their Main Characteristics

Meissen figure of a flower seller from the Cris de Paris series. © AG Antiquités

These fruit-and-vegetable sellers belong to the genre scene category. Such scenes had a growing popularity in the 18th century. There was a clear trend of representing the people in their everyday lives including their work lives. Focusing on porcelain, an art that was both fashionable and with a wider distribution base than fine art in the mid-18th century, Meissen created a figurine line of street traders called “Cris de Paris” based on watercolors made in 1753 by Christophe Huet. Out of the 34 characters, half of them were male and half were female, often working in pairs. Such figurines may very well have been a source of inspiration for Hardy.

Genre scenes leave a large array of possibilities outside of professions. Hardy favored intimate scenes or moments illustrating a character trait or life hardships. Outside of genre scenes, Caspar Bernhard Hardy’s talents explored historical figures and allegories.

The winsome gardner, an allegory of autumn by Caspar Bernhard Hardy. © Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

Many museums have Hardy’s wax specimen. The Musée Carnavalet in Paris even has 13 of them. Yet, these days the largest collection of Hardy’s waxwork gathered in one place is in a much smaller space than a museum: a cabinet.

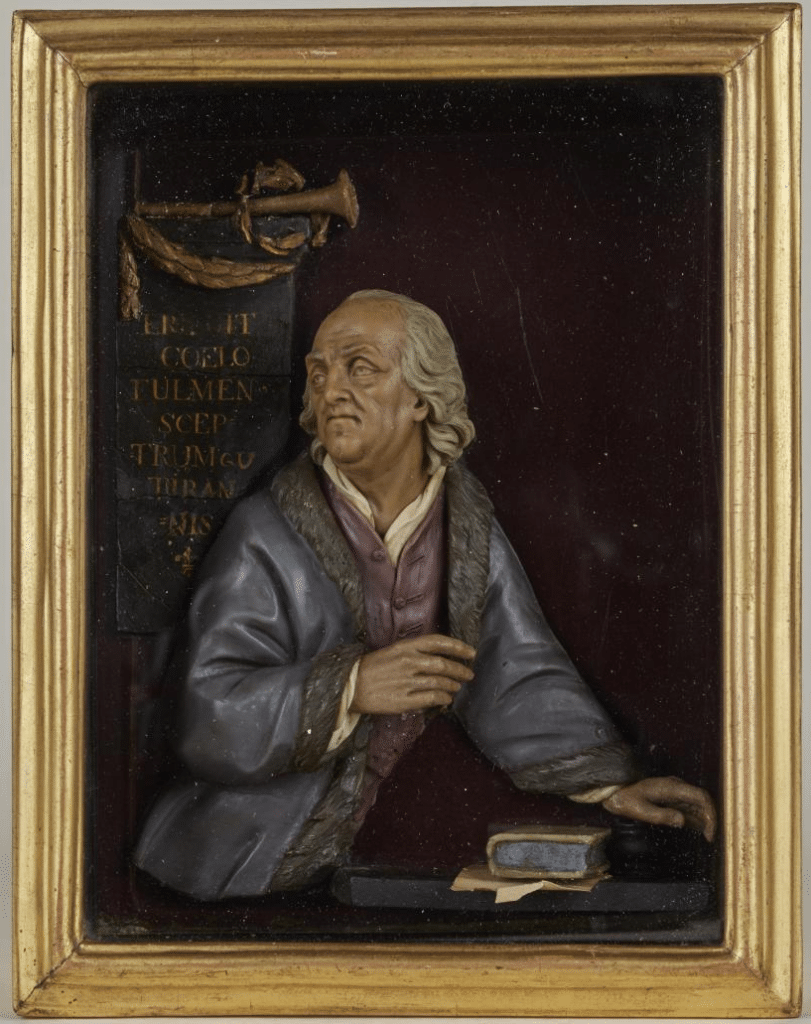

Benjamin Franklin by Caspar Bernhard Hardy in Musée Carnavalet. Public Domain.

This cabinet made around 1795 contains 48 wax sculptures of Hardy. But let us pause for a moment on the cabinet itself. Made of cherrywood inlaid with brass and satinwood crossbands, the cylinder bureau hosts a mahogany panel with a JWL monogram standing for Johann Wilhelm Neel, the Cologne canon who commissioned it. It was made by Theodor Commer (1773-1853), an apprentice of Abraham Roentgen (1711–1793) who supplied German and Central-European princes.

Theodor Commer Cabinet with Caspar Bernhard Hardy’s Wax Reliefs. © Christie’s

This cabinet of curiosities devoted to a single artist is quite a luxurious staging, like a shrine to his work. We can view it as a living proof of Caspar Bernhard Hardy’s fame during his lifetime.

What We Know of Caspar Bernhard Hardy (1729-1819)

Hardy was known all over Europe for his wax art even before he was ordained a priest in 1754. He was born and lived his whole life in Cologne—a free imperial city of the Holy Roman Empire, now in Germany.

Although mostly known for his wax sculptures, he was altogether a representative figure of the Enlightenment with multidisciplinary knowledge and expertise. He was a well-rounded artist: a sculptor (not only of wax since he also carved cameos and casted bronze), a painter, and an enameler. Furthermore, he showcased his physics and clockmaking skills when he fabricated a planetarium.

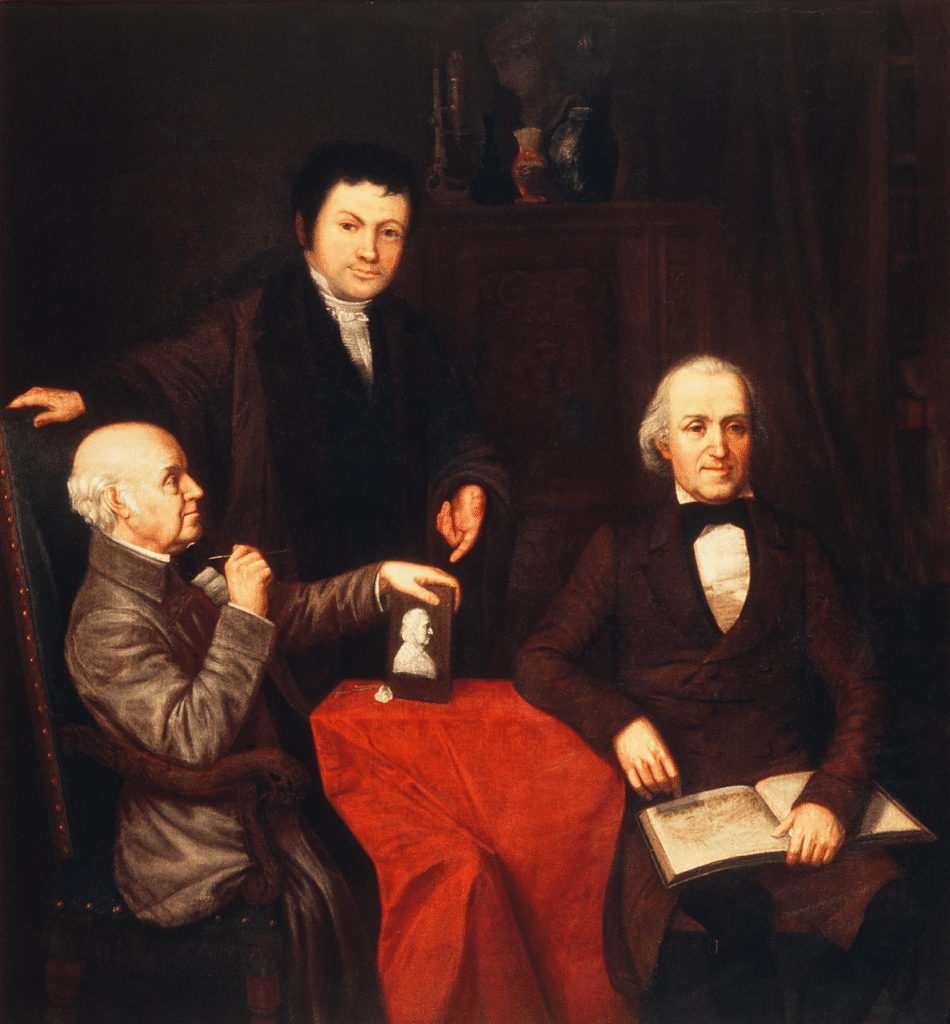

Caspar Benhard Hardy, Mathias Josef de Noel and Ferdinand Franz Wallraf by Everhard Bourel. © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

How do we know this when the artworks we can see today are in the vast majority wax reliefs? This is essentially thanks to his profile included in the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie published in 1879 (only 60 years after Hardy’s passing) and an Ode an Hardy made of 43 stanzas written by Ferdinand Franz Wallraf. Yes, you are reading this right: we are here referring to the famous Wallraf whose collection is at the onset of the current Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne. Indeed, Hardy first was the artistic mentor of Wallraf, but above all, both men developed a long-lasting friendship.

Portrait in marble of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe by Caspar Bernhard Hardy. © Walter Padovani

As for Hardy’s reputation, Goethe himself wrote in his Begegnugen und Gespräche (1815-1816) that Hardy attracted as many visitors to Cologne as a monarch. The illustrious German author met Hardy in 1814 and purchased eight wax reliefs from him. He unequivocally was a fan of the reliefs, writing: “They deserve to be shown in a museum in Cologne for they clearly demonstrate that we are here in the city of Rubens, in the Lower Rhine, where color has always dominated and exalted works of art.”

Wax Reliefs, a “Forgotten” European Art Tradition

If we were doing a poll to know what comes to people’s minds today when we mention wax sculptures, Madame Tussauds would probably surface as the number-one answer. Unfortunately, this entertainment dimension is likely to have tarnished the aura of waxworks. In a way, wax art was a victim of its popular success.

Sleeping Beauty by Philippe Curtius. Her traits would be inspired by Jeanne du Barry, Louis XV’s mistress. © Regan Vercruysse. Temporary exhibition at The Met. From Madame Tussauds, London.

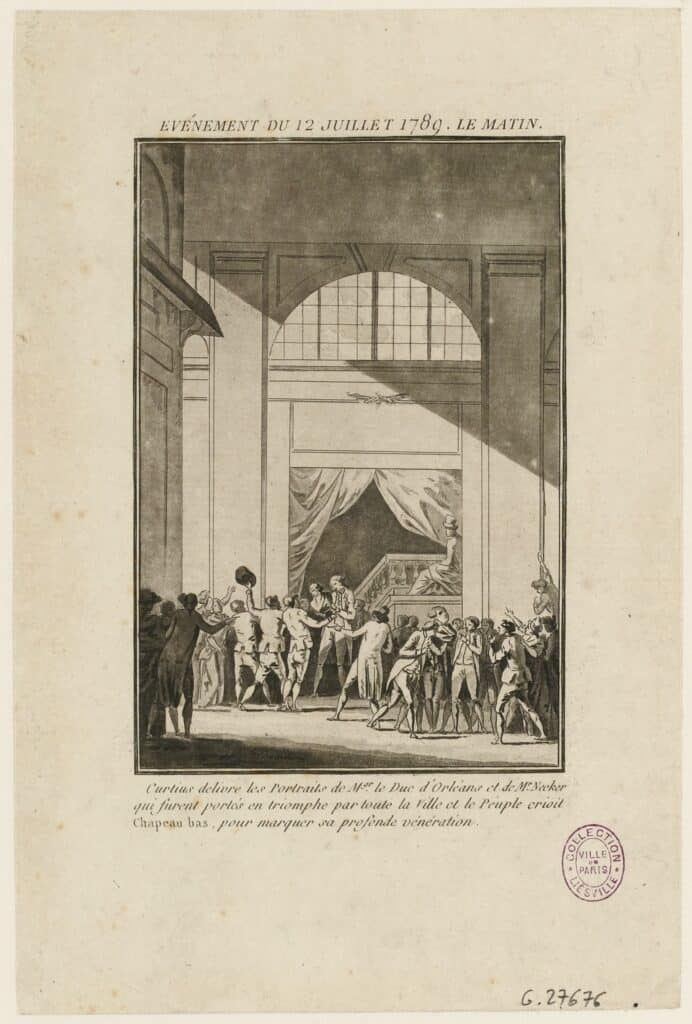

Madame Tussaud (born Marie Grosholtz, 1761-1850) was a pupil and protégée of Philippe Curtius (1737-1794). Curtius first used wax for anatomical studies as doctor in Bern, Switzerland. Somehow, he got the attention and patronage of the Prince de Conti, who convinced him to come to Paris to exhibit his waxworks there, which he did from 1766 on with considerable success as a commercial enterprise in various locations, including the Palais-Royal. He was portraying the famous and infamous. Two of his busts, Necker and the Duc d’Orléans, were even borrowed and paraded on July 12, 1789 during the French Revolution.

Curtius delivers the portraits of Mgr le Duc d’Orléans and Mr. Necker. Engraving by Jean-Francois Janinet at the Musée Carnavalet. Public Domain.

Creating commercial wax galleries was not a phenomenon limited to France and the United Kingdom. In Vienna, Count Joseph Deym von Střítež (1752-1804), aka Joseph Müller, ran a similar art gallery with lifelike wax portraits from 1789 to 1804.

Realism and a simple creation process were the crucial tangible attributes of wax sculptures, explaining its success at a time without photography. Antoine Benoist (1632-1717) at the Louis XIV court had the official title of “painter of the King and his only colored wax sculptor.”

Louis XIV by Antoine Benoist. © Château de Versailles, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Louis XIV commissioned several portraits, among which the one kept at the Palace of Versailles, “Portrait of Louis XIV at 68, Seven Years Before His Death (1706)”, is likely to be the most realistic portrait of the Sun King as it was made from life. Now, such crude realism is even unsettling, is it not? Apparently, it pleased the king. He granted the privilege to Benoist to create a gallery to exhibit the portraits of the royal family and his court in Paris and other temporary locations across France.

This tradition of using polychrome wax sculptures as a public representation of the royals and the rulers goes back to the Middle Ages with votive statues documented, for instance, in Italy, Austria, and England. The powerfuls also valued collecting wax artworks in their cabinets of curiosities for their colors (or stone imitations), their highly detailed work, and sometimes because of their striking renditions in the vanity genre. Caspar Bernhard Hardy’s work is a continuation of the cabinet of curiosities heritage, yet integrating it with an 18th-century mindset showing an interest for both the people and the famous.

Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol by Francesco Segala (1535-1592). © Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

Wax theater ‘The Plague’ by Gaetano Giulio Zumbo (1656-1701). Zumbo was invited to Florence by Cosimo III de Medici. © La Specola, Firenze

You May Like

Curiosities | Collections | Miniatures | Still Life | Portraits | Cabinets| 18th-Century Art & Antiques

[…] medal cabinet created for Louis XVI. It integrates wax panels (remember how we talked about the forgotten art of wax) on which plants, feathers, and butterfly wings were applied and protected by glass. Intriguing, […]

[…] The realism of the Nativity figurines is remarkable, particularly in the portrayal of secular characters, who often possess uniquely distinctive faces. This interest in common people is not without reminding us of the growing popularity of genre scenes in the 18th century as we discussed in our article on wax reliefs. […]