The dragon—long 龍 in Chinese—is far more than one of the 12 Chinese zodiacal signs. It is the prevailing symbol for China and runs deep in the Chinese culture. The dragon is a complex assemblage of multiple cultural facets in a long Chinese history. In Chinese arts, the ubiquitous scene of a dragon going after a flaming pearl is our starting point to explore dragon stories and symbolism. You are about to discover how the dragon went from being a constellation to a guardian and the emblem of the Chinese emperor.

Chinese painted armchair c. 1900 boasting dragons with pearls in their mouths as well as a facing dragon on the top rail. © Galerie LMG

Chasing the Flaming Pearl

A dragon is playing with a pearl among clouds, chasing it. Because the scene takes place in the sky and the pearl is surrounded by flamelike swirls, we are tempted to think the pearl represents the sun or the moon and the dragon swallowing the pearl could induce a solar or lunar eclipse. Yet, more than a celestial body, this pearl symbolizes wisdom, knowledge, and perpetual changes (and the potential that goes with them). Once imperial authority adopted the dragon as its symbol, the pearl also became the emperor’s irrefutable wisdom.

A determined dragon is going after a flaming pearl. Its sinuous body circles the cup, vanishing and appearing amidst clouds. From a set of six porcelain cups and saucers from the Yongzheng period (1722-1735). © Menken Works of Art

The dragon-pearl combination seems to make a beginning during the early Tang dynasty (618-907 CE). However, examples of a vigorous dragon (without a pearl) circling a jar or vessel were found dating from the 2nd-1st century BCE. We have to admit that a dragon has extraordinary ornamental qualities. It fills any kind of space thanks to its long shape and can embellish all kinds of surfaces.

Pair of Nanking crackle vases with two five-clawed dragons and a flaming pearl. © AD 126

Approaching the Chinese dragon iconography with the dragon and a flaming pearl is compelling in many ways. The dragon is the most popular subject of ceramics in China and out of all dragon representations, a dragon or several dragons cavorting through clouds or confronting each other to catch a pearl is the most common one. This pervasive dragon scene perfectly illustrates the symbolic complexity of the awe-inspiring beast. It is at the junction of the dragon of Chinese folktales (related to water, fertility, and nature) and the mythological dragon (a supreme and cosmic power).

The Dragon, Master of Rain and Waters

Typically, in its endless chase after the pearl, a dragon is seen emerging and disappearing in the mist or wrapping around clouds, various shapes of water in the air, connecting the earth and the sky. The rain is its condensed breath. A tornado in Chinese is called “the wind whirled by the dragon”, longjuanfeng 龍捲風. The dragons command the rain and control the waters. It explains why in the folk tradition they are particularly associated with rivers and lakes—40 Chinese rivers contain the word “dragon”.

There are numerous Chinese paintings and prints depicting mountains and rivers, a favored habitat for dragons. This 20th-century artwork is clearly inspired by the classic “A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains” by Wang Ximeng (1096–1119). Mixed media on paper mounted on silk. © Crozon Antiquités

The dragon is nature. More specifically, the forces of nature (or we could say the supernatural principle driving it) and the unpredictably and transformations of the world around us. Water is the strongest element of nature to represent both life and death. Humans cherish the source of water on earth and dread weather perils. Northern China, prone to droughts and the disastrous floods of the Yellow River, has a prolific tradition of legends involving dragons.

The control of water by legendary King Yu is a quintessential myth demonstrating the power and metamorphosis of dragons as well as the appropriation of their powers by the rulers. Yu the Great with his father Gun supposedly created the first Chinese dynasty, the Xia (roughly 21st-17th century BCE). Without going into the details of the story, in a search to control a flood of the Yellow River after a deluge, two kinds of dragons came into play. First, when Gun died, a dragon—who is also his son Yu—came out of his body and became human. Later on, Yu received the help of a yinglong dragon (a winged dragon, which is relatively rare for a Chinese dragon) to mark with its tail the channel where the overflowing water should go.

The Dragon as a Guardian: From the Constellations to the Four Symbols

The dragon also designates a group of seven constellations in the Chinese sky. They appear in the east in spring, which explains the association of the creature with this season and why it is said that for the spring equinox, the dragon rises up to the sky, and goes back hiding in the waters for the fall equinox. Thus, the dragon represents the spring season with the nurturing rains and lengthening warmer days. The dragon rises like the sun.

19th-century lacquered tray during the Qing dynasty. The sun shines above three five-clawed dragons with the flaming pearl. The four bats in the corners are here for good fortune. In mandarin, “bat” and “happiness” are homonyms, pronounced fu. © Galerie La Belle Epoque

Maybe because of this association with the eastern quadrant of the sky, the dragon is identified as a directional figure. Liu An, who died 122 BCE, achieved a complex cosmology work. In the Tianwen chapter of his Huainanzi book, the universe is divided in five directions (four cardinal points and the center). Each direction is protected by a guardian. The four cardinal points are known as the “four symbols” represented by these guardians:

- The azure dragon (qinglong 青龍) for the east and the spring season.

- The white tiger (baihu 白虎) for the west and the fall.

- The vermilion bird (zhuque 朱雀) for the south and the summer.

- The dark warrior, or tortoise with a snake, (xuanwu 玄武) for the north and the winter.

We found one representation of them in a tomb at Xishuipo in Puyang, Henan province, dating from the Neolithic Age (about 6,000 years ago). As protectors, they were often represented on palaces and public buildings. Sometimes simplified to only two of them, the dragon and tiger.

A green-glazed pottery tripod incense burner from the Han period. Decorated with a dragon and a tiger among other creatures. © Conservatoire Sakura

In this system, the center is the earth, guarded by the yellow dragon. This dragon and color became symbols of the Chinese emperor, the Son of Heaven.

The Emperor as the Dragon

This is a large polychrome lacquer box of the Qianlong period (1735-1796) carrying clear imperial attributes. With five five-clawed dragons on the top and more of them, ascending and descending, on the 16 lobes. There is a similar box in the Shenyang Palace Museum. © Binnenweg

The dragon-emperor transfiguration shows in the King Yu’s legend told earlier. Yu’s story didn’t go into writting before the Han dynasty, i.e. 2,000 years after his presumed life. This timing coincides with the emergence of another origin myth for the emperor Liu Bang (or Gaozu) who reigned between 206-195 BCE, founder of the Han dynasty.

The story (recorded in first century BCE) goes like this. Liu Bang’s mom was resting by a river when she dreamt that she encountered a god. Her husband—in the flesh, not in her dream— was passing by when he saw the sky growing dark, filling with thunder and lightning. Amazed and looking more closely, he saw a dragon over her. She was then pregnant and later gave birth to Gaozu. This sacralization of the emperor to legitimize and strengthen his power is familiar to Western minds as well as kings were often attributed divine origins.

It is not until the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) that the dragon became the chief emblem of the emperor. The representation of the dragon (and the phoenix as its female counterpart embodying the empress) was greatly encouraged in decorative arts. Jiajing (1507-1567) would be the first emperor who used the iconic Dragon Throne still present today in the Palace of Heavenly Purity in the Forbidden City.

A dragon and a phoenix painted on a Chinese wood-and-leather pillow of the late 19th century or early 20th. © Galerie La Belle Epoque

The Qing further re-inforced the dragonesque imagery. Qianlong (r. 1735-1796) strictly codified the Qing robes with the 1759 regulation. Not that the emperors didn’t wear dragons on their robes before, but a combination of a specific yellow shade, the five-claw dragon, and the use of all Twelve Ancient Symbols became a strict imperial privilege.

A couple of Chinese ancestors on silk paper from the Daoguang period (1820-1850). The peacock mandarin badge of the man tells us he is a third-rank civil officer. He and his wife both have several four-clawed dragons on their robes. Technically, with one less claw, such a creature is not a long dragon, but a mang python, respecting Qianlong’s regulations. © Galerie des Rosiers

What a Chinese Dragon Looks Like

Mythical creatures have their reality of course as people somehow see them, and also imagine and portray them. Based on archeology, dragons go back to the neolithic times, but they took their more or less final form during the Han period (206 BCE – 220 CE). It is difficult to understand how it crystallized. Their composite appearance may even draw inspiration from the West, considering the earlier Chinese versions.

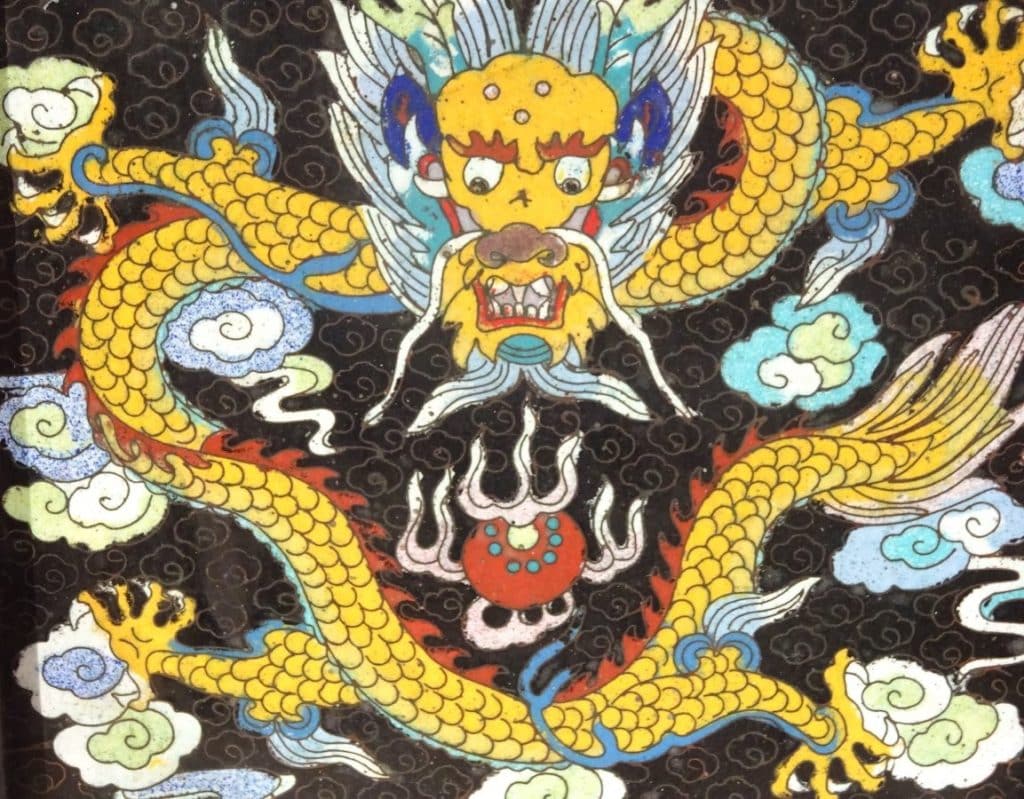

The yellow five-clawed dragon of this 19th-century cloisonne opium tray perfectly matches the Eryayi definition. © Galerie Delalande

According to the Eryayi 爾雅翼 “Wings of the Erya”—an extension of the Erya (the first Chinese dictionary) focusing on plants and animals written by Luo Yuan (1136-1184)—, they look like this:

“Dragons have horns like a deer, a muzzle like a camel, eyes like a demon, a body like a snake, a belly like a crab, scales like a carp, claws like a hawk, legs like a tiger, and ears like an ox.”

Note that a composition based on nine animals is no accident for dragons. The number nine symbolizes completion, longevity, and is the number of the emperor.

However, a creature with such a complex history can’t boil down to a single and simple definition. Not only does a dragon appearance evolve as it ages, but there are also several types of dragons (like for instance the winged yinglong dragon we talked about earlier) depending on where they live (e.g. river, sea, mountains, underground) or some specific physical attributes or powers.

Note the two different types of dragons on this pair of Chinese cloisonne incense burners. Each lid carries three dragons. The big one in the middle is of the classic Eryayi form. The two small dragons for the handles are jiaolong, aquatic hornless snake-like dragons. © Tobogan Antiques

####

The Chinese emperor was overthrowned over a century ago. However, dragons didn’t go away with him. Today, all Chinese are “Descendants of the Dragon”, the title of a popular song written in 1978, and the dragon is a national symbol.

You may have noticed thanks to the various stories developed in this article that, contrary to the Western traditions, the Chinese dragon is not malevolent. This dragon is essentially auspicious, even if the respect it inspires is tainted with fear. Power is danger.

####