I am a student of my father and beautiful nature.”

— Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

Rosa Bonheur (née Marie-Rosalie Bonheur in Bordeaux, France) was amongst the most illustrious and successful painters of her time, selling her artworks internationally. She was such a celebrity that a doll was made in her likeness and was a popular toy in the United States. Many do not realize it nowadays as her realistic manner fell out of fashion with Impressionnism and later styles. Let’s discover her today through the lense of her painting ‘Cows in a Meadow’.

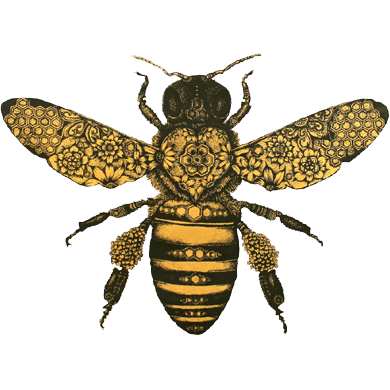

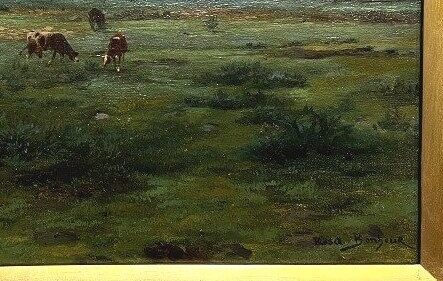

Cows in a Meadow by Rosa Bonheur © Martine Boré Antiques

A Truly Bucolic Landscape Painting From the Vente Rosa Bonheur 1900

Looking at this oil painting is like a taking a walk in the country side. This is a bucolic landscape in the literal sense of bucolic, which comes from the Greek boukolos for cowherd. This painting with cows grazing in the distance is familiar of Rosa Bonheur’s work while also somewhat surprising compared to her most famous works.

Surprising because the cows are merely in the background, nothing like the famous and majestic close-up portraits of a stag, a lion, a dog or other animals that she did. The grass area is predominant and the tree line in the back defines the horizon as mountains would. Thus, this is a landscape. Yet, the cows are unequivocally the focus point of this painting.

Close up of the cows and grass © Martine Boré Antiques

Familiar because of the serene realism of these animals in their element, the paradox of domesticated animals is that, when not surrounded by men, they could be mistaken for wild animals. This painting leaves a lot of space to nature. These cows in a green pasture are in fact more reminiscent of the landscapes she did, inspired by Fontainebleau, Scotland, or the Pyrénées, for instance.

Her talent for texture and light shines thanks to a rich green palette for the grass, represented with vivid strokes, and her skills to represent the shifting grey skies. What she once said comes to life here:

When you want to paint a sky, start with the lighter side, that is to say the background; on it you will lay the grays and so on. The color should be cheerful and shimmering in the lights; the shadows, on the contrary, must remain transparent.”

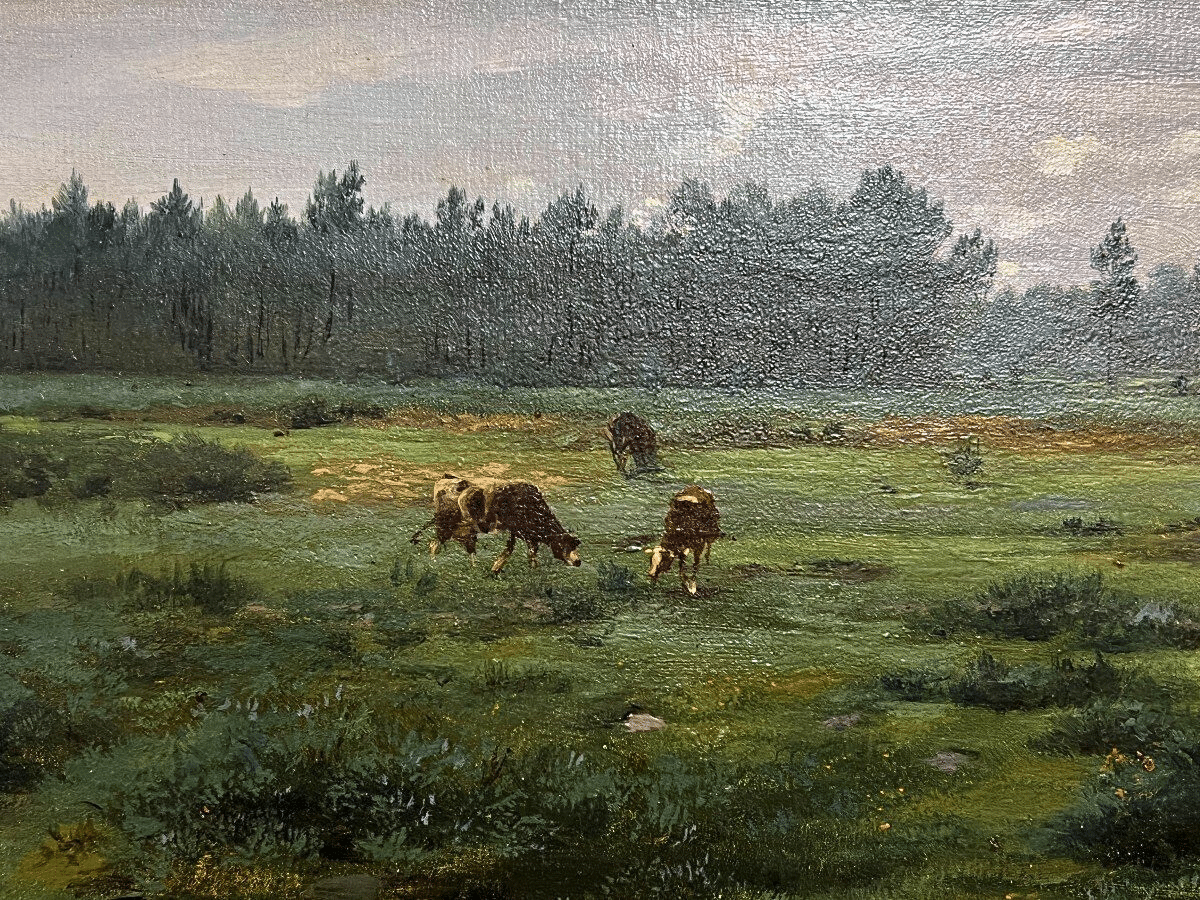

On the back of the frame: Red wax stamp VENTE ROSA BONHEUR 1900. © Martine Boré Antiques

On the back of the frame, a red wax stamps reads VENTE ROSA BONHEUR 1900. This posthumous sale of artworks from her study and her own collection comprised 2,100 references. Decided by her universal legatee, Anna Klumpke (1856-1942), it took place at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris from May 30th to June 8th, 1900—approximately one year after the artist passing.

Left corner: Rosa Bonheur stamp. © Martine Boré Antiques

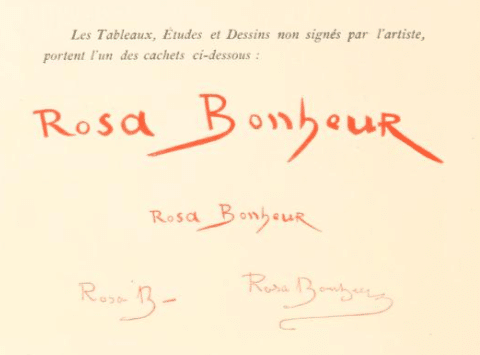

Consistent with the sale wax seal, what first looks like a signature of Rosa Bonheur in the bottom left corner of the front is most likely a stamp (un cachet) as mentionned on the first volume of the Rosa Bonheur’s workshop sale catalog (Catalogue Atelier Rosa Bonheur – Tome Ier Tableaux).

“The paintings, studies and drawings not signed by the artist carry one of the stamps below:”. Section of the Sales Condition page in the original catalog of the paintings sale.

Animals and Realism

In 1857, when Edouard Dubufe (1819-1883) represented Rosa Bonheur on foot, she was originally leaning on a table. Rosa Bonheur modified it herself. Instead of “a static piece of furniture” (as she said herself), she painted a bull. She is forever standing by the side of one of her true companions. This is how important bulls and cows were to her.

Portrait of Rosa Bonheur in 1857. By Edouard Dubufe and Rosa Bonheur. © RMN (Château de Versailles)

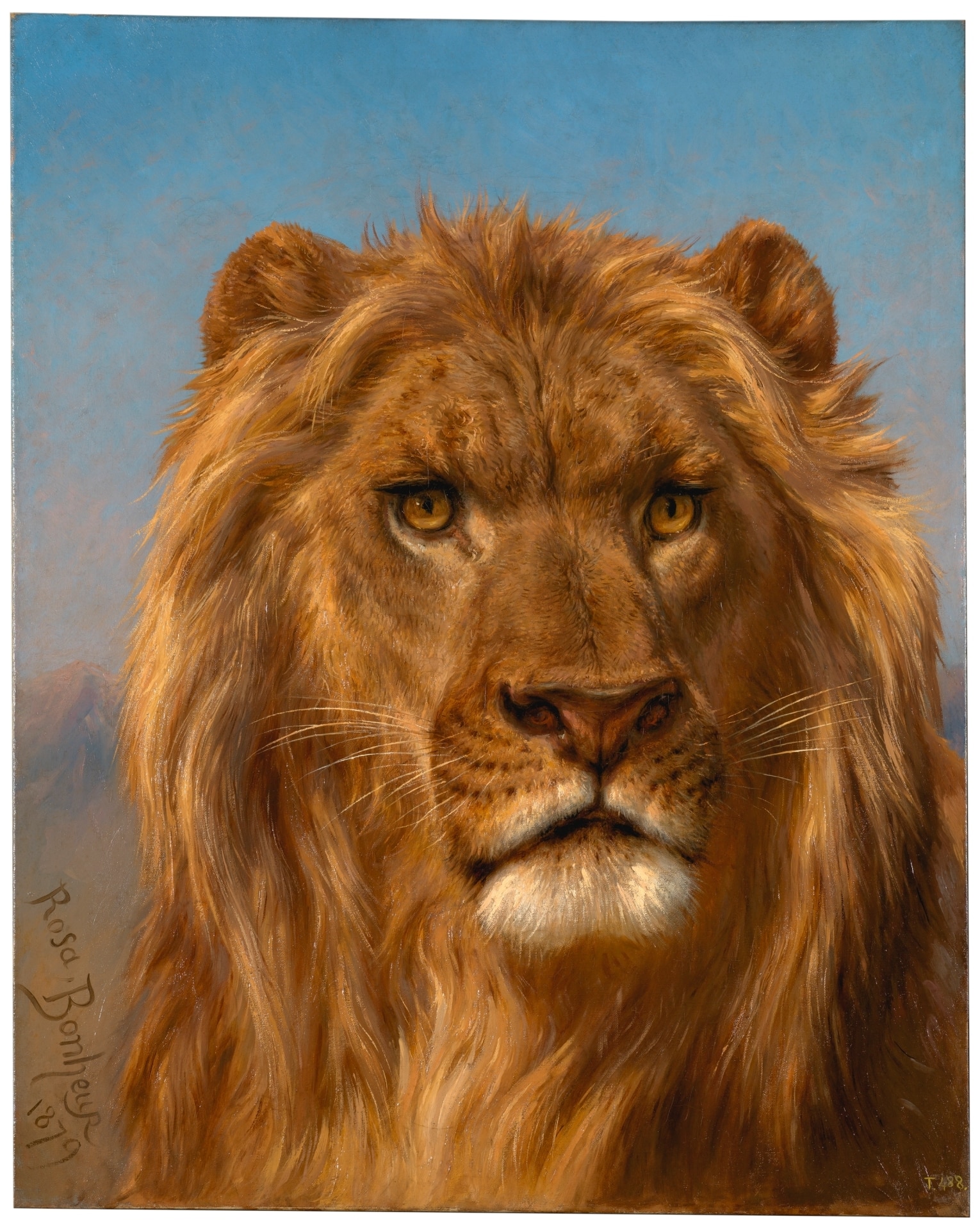

But Rosa Bonheur did not stop at oxes. Whatever the animals (essentially mamals), there is no doubt that they were the heroes of her art. She drew and painted numerous goats, sheeps, horses, donkeys, rabbits when it comes to domesticated animals. Wild animals as well. For instance, foxes, wild boars, even a royal tiger, and the most famous deers and lions.

El Cid by Rosa Bonheur © Museo Nacional del Prado

She was also a sculptor, even though she prefered to leave the animalier sculpture field to one of her brothers Isidore Bonheur (1827-1901) to limit competition within the family.

Bull bronzes by Rosa Bonheur © David Picard Antiquités

She practiced her arts in the realism vein. But never a kind of realism that would include social drama and imply a specific political agenda (as Gustave Courbet did). She was not revolutionary this way. Animals and nature were all she focused on (even when included in a rural scene) and for this reason, she can also be associated with naturalism. She unambiguously went for biological accuracy when she drew some zoological illustrations of Cattle Breeds at the Paris Universal Agricultural Competition in 1856: Zootechnical Studies (Les Races bovines au Concours universel agricole de Paris en 1856 : Études zootechniques ). Look specifically at the XVIII, XIX, LIX, LX, LXI illustrations.

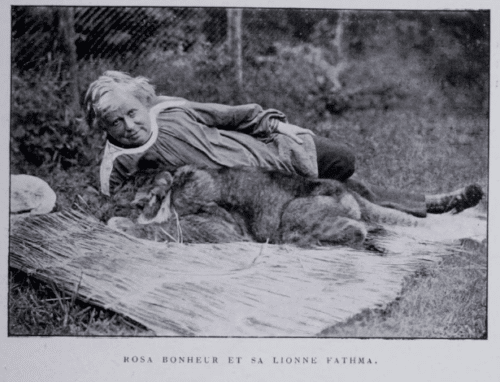

Because objective realism mattered so much, she wanted to repeatedly draw the animals based on live specimen as much as possible. It was not enough for her to copy old masters, study livestock at markets and slaughter houses, or visit animals at zoos. She wanted to catch them in a more natural or comfortable setting. For this reason, at home not only did she have pet animals, but she also had on premises a sort of farm/menagerie. Once she settled in her big property of By in Thomery near Fontainebleau, she came to host around 200 animals, domesticated or wild. She got an outdoor workshop that she called her “pavilion of the muses” in the middle of her park, which enabled her to observe and draw them without getting their attention. At some point, she even took care of two lion cubs. One of them, Fathma, became a docile lioness who could roam freely in her castle.

Rosa Bonheur and her lionness Fathma © Château Rosa Bonheur By-Thomery

She always tried to depict the animals as themselves and never fell into anthropomorphism. They certainly did not have to be humans to deserve attention and care: they were living creatures. She once said: “One thing I watched with special interest was the expression in their eyes; is not the eye the mirror of the soul for all living creatures?” Their soul being their individuality. Moreover, the expression of an animal at a particular moment could also be representative of their species or breeds. When looking at her art, we generally notice the power and candidness of the animals, their undivided presence in what they do.

Barbaro after the hunt by Rosa Bonheur © Philadelphia Museum of Art

Landscapes and Nature

There has been less research on Bonheur’s landscapes, which makes it more difficult to elaborate on her own motivations. She did say to her dear friend Anna Klumpke (who joined her on her property in By and started working on her biography in 1894): “Dear Anna, I hope to make you love landscape, one experiences so many moving sensations when studying it.”And “If I were not on the decline of life, I would devote myself to the landscape, for which I have always been passionate.” Arsène Houssaye (1814-1896), who for a time was general inspector for the Ministry of Fine Arts, said of Rosa Bonheur: “If nature is master of masters, we can say that Miss Rosa Bonheur, landscaper, took nature as her workshop.”

Misty Landscape by Rosa Bonheur © Private collection. Presented at the Fitzwilliam Museum during the temporary exhibition Open-air Painting in Europe 1780-1870 in 2022.

Being “a student of […] beautiful nature,” landscapes could only belong to her realm of expertise to express here again the grandeur of nature. The landscapes were also these territories were the animals she cherished lived.

Similar to her method with animals, she had to experiment for herself what she was painting. Early on in her career, she traveled in rural areas. She went to Auvergne and Cantal in 1846, to Nivernais in 1847, and the Pyrénées in 1849. She traveled through England and Scotland in 1856. An artist with such a strong connection with nature had to narrate her travels with studies and paintings.

Pasture in the mountains by Rosa Bonheur © RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Fontainebleau)

In 1859, after the tremendously lucrative sale of her painting Le marché aux chevaux, she could afford the acquisition of the Château de By in Thomery. She was living on the edge of the forest of Fontainebleau. At the zenith of her career, it was her choice to exile two hours away from Paris by train (at the time) to get away from society life and follow her passions.

Rosa Bonheur and her dogs near Thomery in 1898 © Château Rosa Bonheur By-Thomery

In Fontainebleau, every day, she was leaving at dawn, walking or taking a horse carriage. Her favorite spot was the gorges et platières d’Apremont. The Fontainebleau forest was already a place privileged by landscape artists, especially by Camille Corot (1796-1875), who in the early 1820s started to practice there and initiated this way the School of Barbizon (which was in no manner an organized or formal art movement). Despite the influence of this plein-air (open air) art movement and the geographical proximity, Rosa took her own path.

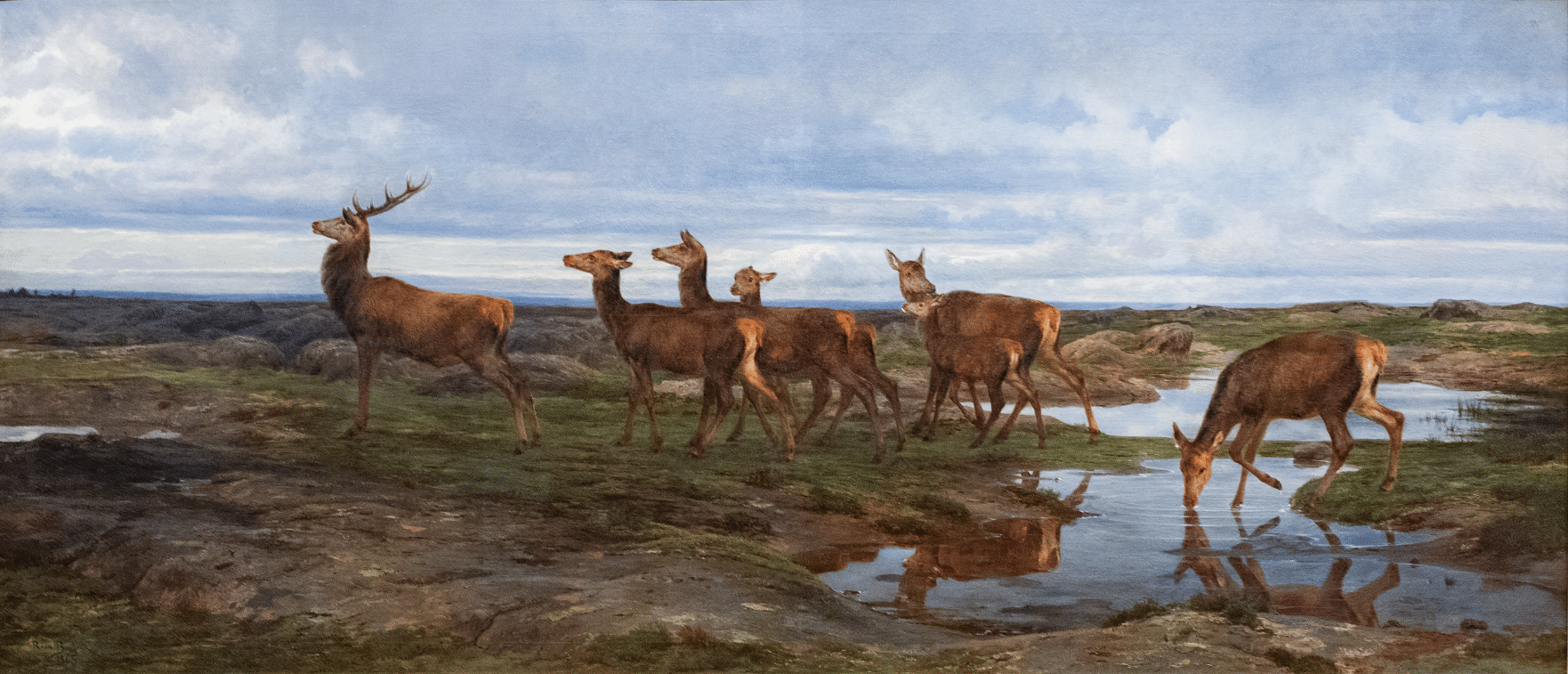

A deer family AKA The long rocks by Rosa Bonheur © The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art

Freedom was a crucial dimension in Rosa Bonheur’s life, which was all the more remarkable for a woman of the 19th century. In a next article, we will explore what fueled her extraordinary destiny, the major highlights and artworks of her life.

You May Like

19th-Century Fine Arts | Landscape Paintings | Portraits (incl. animals) | Animalier Bronze | Rosa Bonheur