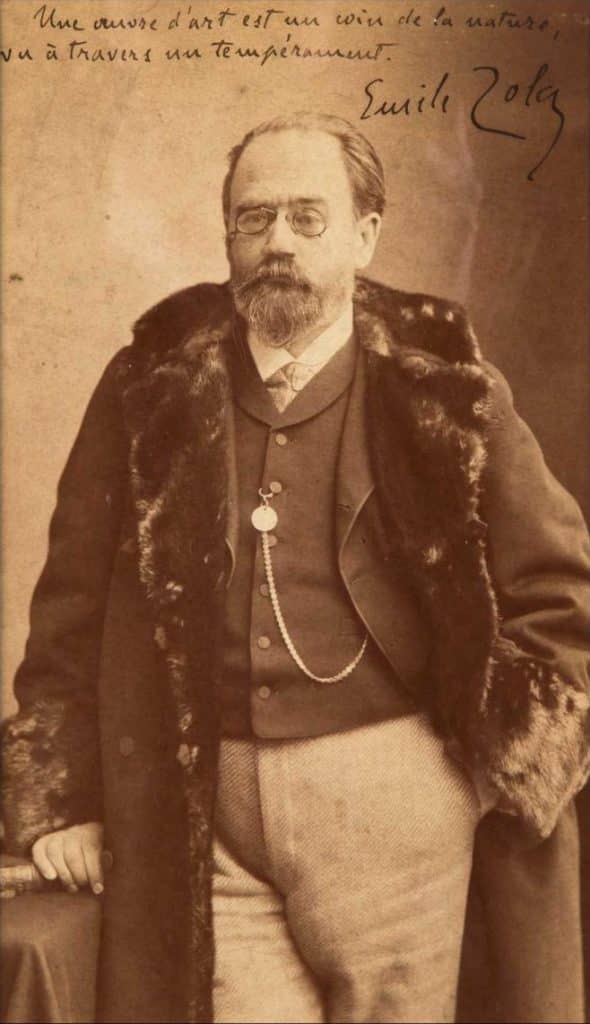

What a fantastic photograph to introduce Émile Zola (1840-1902) in regard to Impressionism! Already an established and affluent writer, Zola is here photographed in 1895 by Paul Nadar. Paul is the son of THE Nadar, the celebrity’s favorite photographer, who lent his former studio at 35 boulevard des Capucines for the first exhibition of the impressionists in 1874.

Émile Zola photographed by Paul Nadar in 1895. Autographed with a famous quote on what a work of art is. © Antiquités Rodriguez Décoration

The picture is autographed by Zola with his emphatic signature (clearly, before a Z stood for Zorro, it did for Zola). But it is the quote above that is of the greatest interest:

A work of art is a corner of nature seen through a temperament.

Nearly 30 years before, this sentence was originally closing an article titled “My Salon (1866): The Realists of the Salon” published on May 11, 1866 in L’Événement newspaper. As a critic, Zola was explaining what he thought of his visit. He was adamant about not trying to defend any painting school in particular and how much he cared for life and truth above all. He didn’t mince his words about the artists who failed to meet his standards. On the other hand, he gave lavish compliments to a newcomer for him: Claude Monet.

Claude Monet According to Émile Zola in 1866: Energy and Truth

You can appreciate here for yourself the glowing review Zola wrote for Monet’s painting titled “Camille”.

Camille by Claude Monet in 1866. Exhibited in Kunsthalle Bremen (Public Domain).

“I admit that the painting that stopped me for the longest time was Camille, by Mr. Monet. This is an energetic and lively painting. I had just walked through these cold and empty rooms, tired of not meeting any new talent, when I saw this young woman, dragging her long dress and sinking into the wall, as if there had been a hole. You wouldn’t believe how good it is to admire a little, when you are tired of laughing and shrugging your shoulders.

I don’t know Mr. Monet, I even think that I had never looked attentively at one of his paintings before. However, it seems to me that I am an old friend of his. And this because his painting tells me a whole story of energy and truth.”

However, 14 years later, if Zola still considered this painting to be a work of excellence and Monet to be a master of his art, he regretted that Monet sometimes took the easy route for economic reasons and sold underworked art.

Émile Zola, a Journalist and Critic Before Becoming a Successful Author

During the 1866 Salon, Zola was not famous yet, but he was starting to be known in literary circles. He had published two books: “Les contes à Ninon” in 1864 and “La confession de Claude” in 1865. He worked at the publishing house Hachette from March 1862 to January 1866. As he ended up managing the advertising service, he had a good grasp of what it takes to make noise and grow a reputation to sell books.

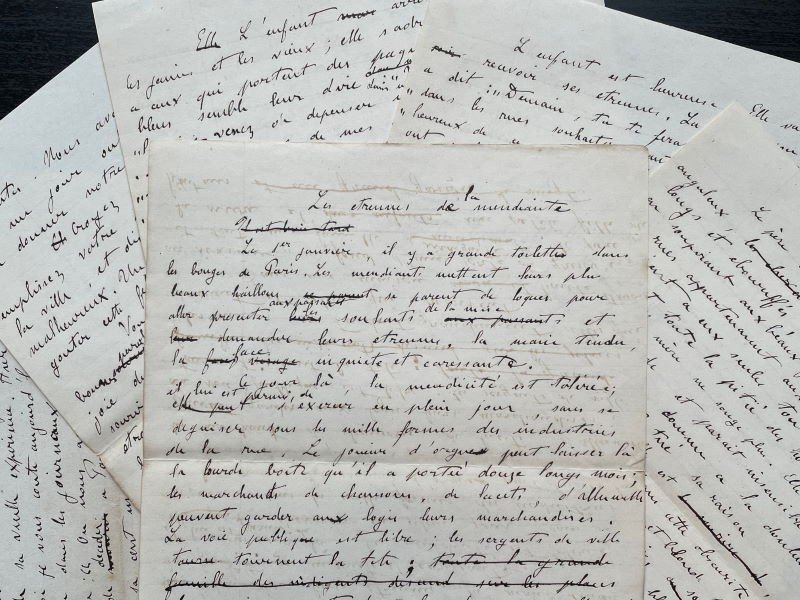

Selling short stories and chronicles to a thriving press enabled him to make a living, promote his books and build a name. “Les étrennes de la mendiante“—the manuscript of which is presented below—is an excellent example. Zola published it on January 21, 1865 as a chronicle in the newspaper Le Petit Journal. This paper was incredibly popular with a circulation of 259,000, greater than the entire Parisian press. Zola became a prominent art critic of his time.

The autograph manuscript of “Les étrennes de la mendiante” by Émile Zola. In this short story, impoverished parents in Paris send their eight-year-old daughter to beg on New Year’s day. © Manuscripta

Achieving Glory: Relentless Work and a Vision of the French Republic

Success came in 1867 with his first officially naturalist novel “Thérèse Raquin“. Zola epitomizes a literary movement, naturalism, culminating with his big oeuvre “Les Rougon-Macquart“. This cycle of 20 novels published between 1870 and 1893 depicts life under the 2nd Empire (Napoleon III) as we follow five generations of a family.

With naturalism, Zola wanted to have a scientific approach to his stories and characters, with no moral judgement. His novels showcase people whose behaviors are circumscribed by social and biological determinism.

Zola became a popular but divisive author because of his views, which were not strictly speaking socialist, but unambiguously republican (as in anticlerical and opposed to the empire or monarchy). Several of his novels had resounding success.

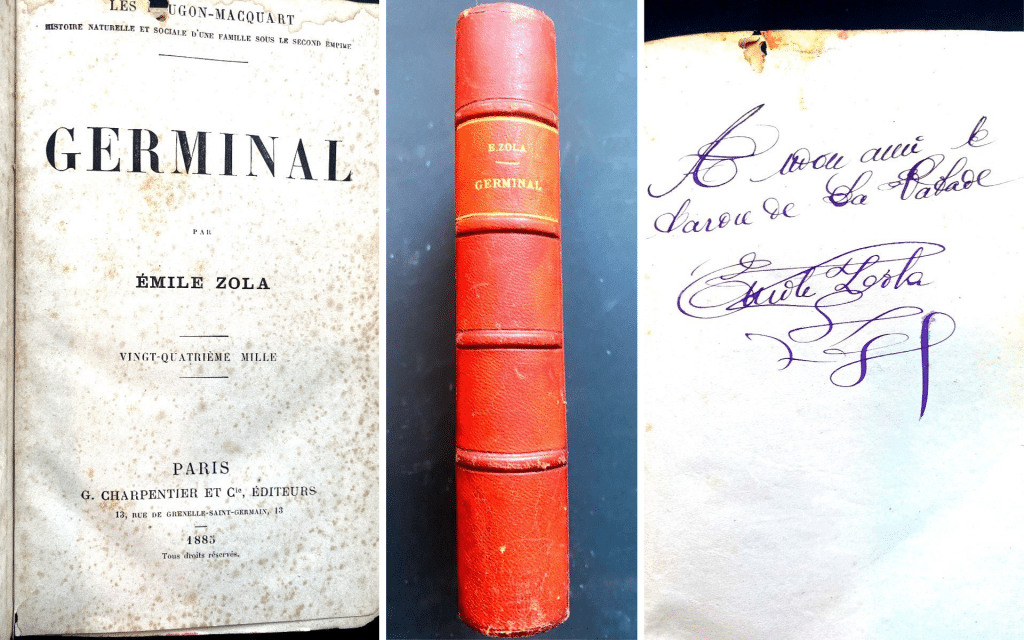

First original 1885 edition of “Germinal” by Émile Zola. G. Charpentier et Cie , Editeurs. Bound in red morocco. Dedicated to Baron de la Calade. His wife Alexandrine Zola was sometimes doing such dedications for him. That is why the signature looks so different from Zola’s autograph on the introduction picture. © Antiquaire du Vallon

“Germinal” published in 1885 surpassed them all. It depicts the social distress and oppression of the mining world. To prepare this book, Zola spent a week around Valenciennes and even attended the monumental strike of Anzin that lasted 56 days in 1884 and led to the legalization of unions. At Zola’s burial in 1902, a national event during which riots were feared, miners came and chanted “Germinal!” to pay homage to the author who defended their cause.

And of course, we can not talk of the committed writer and journalist without mentioning the Dreyfus case. Zola tirelessly defended Dreyfus. The famous “J’accuse…!” in L’Aurore in January 1898 was only the stepping stone to a battle that may very well have led him to his death—a theory supported by his thorough biographer Henri Mitterand.

“My Friend, My Brother, Paul Cézanne”

Having now a better understanding of Zola’s ardor, let us come back to his relation with Impressionism. Friendships and his views on art were inseparable. Among all the artists Émile Zola spent time with, Paul Cézanne stands out. Their friendship that started in middle school in Aix-en-Provence lasted all their lives—although you may hear otherwise; we’ll get into that later. As Zola had to leave Aix to finish high school in Paris, the two friends had early on a close epistolary relationship.

Through their letters, we can witness that despite their young age, they are already set on living from their respective artistic passions. In a letter to Cézanne written on March 25, 1860, Zola expresses:

I had a dream the other day. I had written a beautiful book, a sublime book that you had illustrated with beautiful, sublime engravings. Our two names in gold letters shone, united on the first leaf, and, in this fraternity of genius, inseparable as they were going down in history. It’s still just a dream unfortunately.

Cézanne was over 50 years old when he finally obtained artistic recognition. This long journey to success was only made possible thanks to his perseverance and his father’s fortune. This explains why, when Zola published “The Masterpiece” (L’Œuvre) in 1886, Cézanne could have seen himself in the main character Claude Lantier, a choleric and failed artist. It was a plausible reason for breakup between the two friends and a well-known theory.

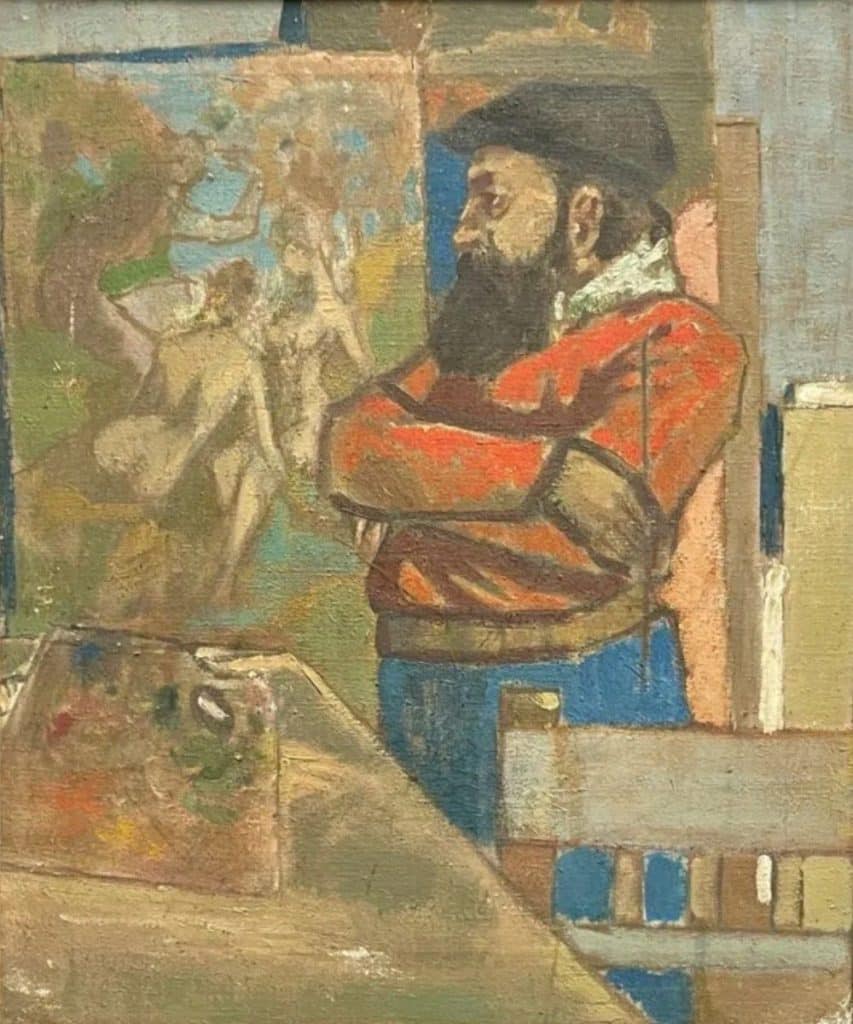

Paul Cézanne standing in front of Baigneuses, one of his recurrent themes. By unknown painter, early 20th century. © Bailliet Antiquités.

However, a 1887 letter between them was found some years ago, which would rather suggest that the later part of their correspondence was simply lost. Most likely, they drifted away progressively, busy with the natural twists and turns of their lives. Congruent with this hypothesis, in 1903 as the city of Aix was paying homage to Zola, Cézanne was among the very few friends to be invited with Zola’s wife. The 67-year-old man wept distinctly as another friend was reminiscing their strong complicity.

When Zola wrote on May 2nd, 1896 in Le Figaro: “I grew up almost in the same crib as my friend, my brother Paul Cézanne“, it did have a tangible meaning about their closeness. Zola organized the first stays of his friend in Paris from 1861 on. They were crucial for the development of Cézanne’s career. Besides, Cézanne was hosted by Zola’s mother in 1863. At the académie Suisse (a renowned and cheap informal art school), probably in 1861 or 1862, Cézanne met Camille Pissarro, then Antoine Guillemet. And this is thanks to Cézanne that Zola was first introduced to the impressionists before they were called so.

Édouard Manet: Admiration and Friendship

Zola was particularly interested in the scandalous painters, those rebuffed by the traditional critic and sometimes rejected by the official Salon. An avant-gardist circle, led by Édouard Manet, was meeting in the café Guerbois in the Batignolles. Émile Zola moved to this artistic district with his mother and partner in 1866, which coincides with his decision to leave his job at Hachette and make a living from his penmanship.

“Un atelier aux Batignolles” painted in 1870 by Henri Fantin-Latour includes Manet, Zola and Monet among other artists and fans. © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

He wrote two reviews in 1866 and 1867 where he passionately defended Manet. He wrote:

Our fathers laughed at Courbet, and now we are ecstatic before him; we laugh at Manet, and it will be our sons who will be ecstatic in front of his paintings.

Zola had a special fondness for the scandalous “Olympia“ painting presented in the 1865 Salon. As a thank-you gift, Manet made a portrait of him in 1868. It sealed the beginning of a long friendship until Manet’s death in 1883. In Zola’s later novel “The Masterpiece”, the painting presented at the first salon of the main protagonist is inspired by Manet’s “Le déjeuner sur l’herbe”.

Impressionism Vs. the Impressionists

Nevertheless, even if Zola stayed on the side of the ideas behind Impressionism, there seems to have been a turning point around 1879. In summary, he was questionning the efforts and quality of the artworks, concerned by a lack of consistency. In “Le naturalisme au Salon“ published in 1880 in Le Voltaire: “This is why the struggle of the impressionists has not yet succeeded; they remain inferior to the work they are attempting, they stutter without being able to find the word. But their influence nonetheless remains enormous, because they are in the only possible evolution, they are marching into the future.” In the same article, Zola stated that Claude Monet was the head of the impressionists who were the “direct sons” of Édouard Manet.

Ultimately, if impressionists had a key role in Émile Zola’s friendships and career, they never beat the painter who consistently kept first place on his artistic podium: Gustave Courbet. He served as the gold standard against which Zola measured all the other painters, impressionists included.

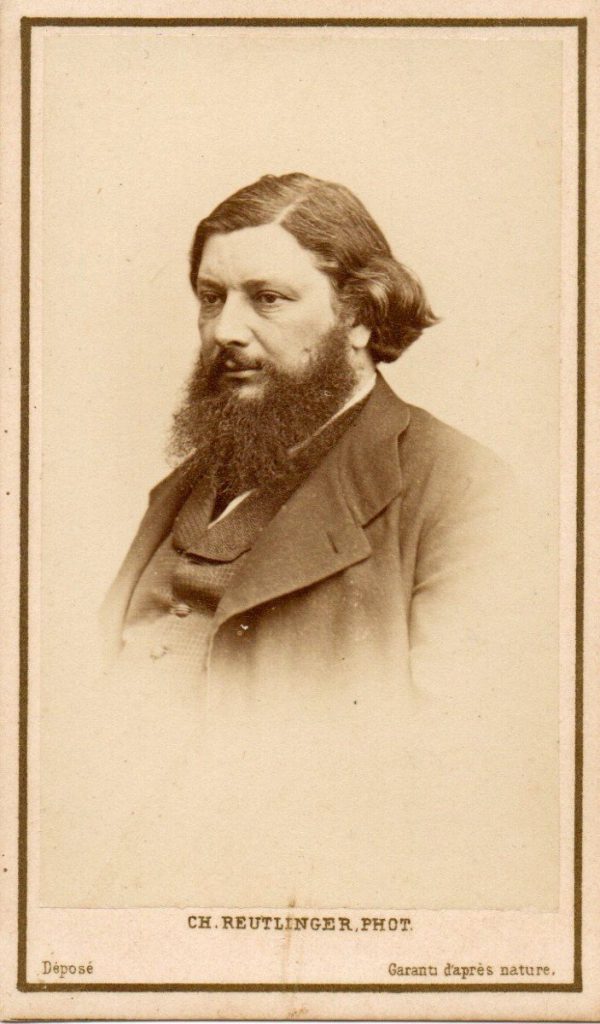

Photo portrait of the illlustrious painter Gustave Courbet by Charles Reutlinger. © La Valise Arlésienne

~

~ MAIN STORY: Impressionism Celebrated by PROANTIC ~

~

You May Like

Émile Zola | 19th-Century Photographs | Old Books | At a 19th-Century Writer’s Desk: Inkwells, Desk Accessories | Portrait Paintings