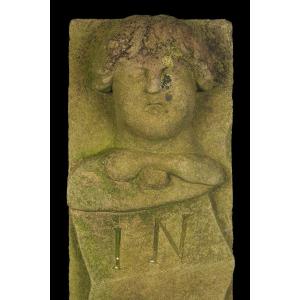

Early 20th century plaster mask.

The mask was recently restored, it had cracks and old restorations, particularly in the neck, which have been taken over. What we see in slight relief today on the face is what we call seams, it is the mark of the mold which is completely original.

One fine day in 1880, the body of a young woman was fished out of the Seine. No trace of bruises or wounds. We end up committing suicide. On his sleepy face, an enigmatic smile is drawn. Fascinated, the forensic assistant decides to make a cast of it. If the practice is then common, usually it is the traits of illustrious men that are frozen in immortality. Yet now in the windows and on the displays of Parisian moulders, between two busts of Napoleon or Beethoven, the Unknown of the Seine has just made its appearance...

This fashion for the death mask may seem incongruous or disturbing to us today, but it is part of the sensitivity of the time.

At the end of the 19th century, it is also a very special place that arouses the enthusiasm of Parisians.

Located on the Quai de l'Archevêché, a stone's throw from Notre-Dame, the morgue is a popular address for city dwellers who do not hesitate to go there with their families for a Sunday stroll. Behind large windows, corpses recovered from the Seine or found in the street are exhibited for possible identification.

In his novel Thérèse Raquin, published in 1867, Émile Zola paints a portrait of the crowd that throngs there every day: “The morgue is a spectacle within reach of all budgets, paid for free by poor or rich passers-by. The door is open, enter whoever wants. There are amateurs who make a detour so as not to miss one of these representations of death.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato