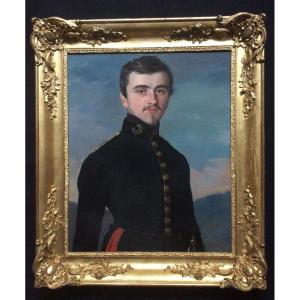

(Bruges 1770 – Bruges 1839)

Portrait of a young woman near a spring, accompanied by her dog

Oil on canvas

H. 73 cm; L. 60 cm

circa 1815-1817

We owe this elegant portrait to François-Joseph Kinson from Bruges, which is still linked to the art of the First Empire. We find in this artist this type of pose that is a bit rigid, sometimes with a countryside in the background, and this way of treating costumes and faces. Thus the full-length portrait of Jenny Cécile de Maillé, marquise de Cubersac (Osenat, November 17, 2013; ill. 1), shows a similar way of installing her model near a tree and a hillock of greenery, in front of a landscape. The same Italian straw hat as in our painting is used as an accessory to this portrait, and we also see a similar one on that of Adèle Auguié, also by Kinson (ill. 2). François-Joseph Kinson made his debut at a very young age in Bruges, Ghent and Brussels. He amassed a nest egg which allowed him to come to Paris where he was naturalized French. Exhibiting his portraits at the Salon from 1799, he conquered a wealthy clientele and painted effigies of the imperial family: Madame Mère, Prince and Princess Borghese, Joseph Bonaparte King of Spain. Appointed first painter to Jérôme Bonaparte in 1809, he followed him to the court of Westphalia and did not return to Paris until after the fall of the Empire. It was to put himself at the service of the Duke of Angoulême, whose portrait he presented at the Salon of 1819. A painter sought after under the Restoration, Kinson was then able to continue a career provided with aristocratic commissions. Our portrait offers a delicious testimony to a pivotal period in women's fashion. The dress is still part of that ancient simplicity that prevailed under the Consulate and the Empire. But there are already some changes: the belt no longer passes under the chest, but goes down towards the waist. Slightly shortened, the dress no longer drags on the ground and is adorned with a braid. Balloon sleeves appeared. The sobriety of this summer dress, of a virginal whiteness, is offset by the brilliance of the red cashmere shawl, whose vogue had been launched by Josephine. The whole indicates a "transition style", allowing us to date our painting from the very end of the First Empire or rather from the first years of the Restoration. Finally, a word about the symbolism of the painting – because there seems to be one. The dog who gazes so tenderly at his mistress is a notorious emblem of fidelity. The ivy garland around the straw hat could signify faithful love, an eternal attachment: “The ivy dies where it clings. ". Louise Cortambert, in her Langage des fleurs (1834), - a romantic dictionary that has been republished many times, which offered a kind of floral Iconology -, recalls that in Greece, "the altar of the hymeneum was surrounded by ivy, and a stem was presented to the newlyweds, as the symbol of an indissoluble bond”. The morning glories growing in the rock seem to double these pledges of friendship and fidelity. The rustic purity of the surrounding countryside, the immaculate white of the dress, reinforce the hypothesis that this portrait is that of a fiancée or a young and chaste wife. We thank Mr. Norbert de Beaulieu for his help in studying the costume and dating this painting.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato