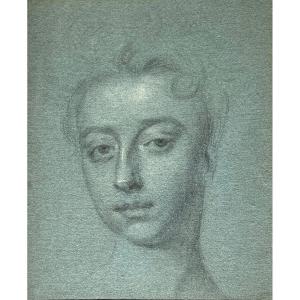

The identification of this portrait is confirmed by the use of an identical head that appears in a 1709 portrait of Congreve by the Studio of Godfrey Kneller (NG 67) in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), London. A close comparison shows the exact same features, including the calm eyes, strong nose and hearty double chin. His appearance here relates to a white chalk and charcoal head study by Kneller that survives in the Courtauld Collection, which may well have been used to produce this painting.

As one of Britain’s most fashionable painters, demand for Kneller’s brush often exceeded his output. To remedy this, the artist employed a vast number of studio assistants to complete copies and variations on the master’s own paintings. Bearing in mind the quality of the handling, it is conceivable that the portrait on offer was a repetition completed by a studio assistant working in Kneller’s studio. Making use of a head study, perhaps the aforementioned Courtauld sheet, the artist working on this picture changed the position of the sitter’s body and placed it within a shady grove. The positioning of the sitter’s hand inside his frockcoat would have presumably had the intention of keeping the costs down. It is known that the inclusions of hands in portraits, a tricky feature for any able artist let alone a studio assistant, could often increase the work’s price.

Kneller included a likeness of Congreve in his famous Kit-Cat series, which also survives at the NPG (NG 3199). This surviving work, in a grand format with exuberant brushwork, is an example of Kneller working at the height of his career. The entire series, which features members of this notorious literary and political club, have come to epitomise British portraiture in the opening decades of the eighteenth century. One imagines that the following studio piece may have been painted for one of the playwright’s followers or friends. Congreve is also recorded to have collected works by Kneller, and is recorded having paid £15 for a portrait of ‘Saint Cecilia’ in June 1703.

William Congreve (1670 - 1729). William Congreve was born in Bardsey Grange, Yorkshire, in 1670. A talent for writing is likely to have descended on his mother’s side. Mary Congreve nee Browning (d.1715) was related to the early modern treatise writer Dr Timothy Bright (d.1615). Mary’s family connections to successful and recently ennobled merchant families helped to raise the her own family’s position during the Stuart Restoration. Despite his Yorkshire roots, William and his family had moved to London by 1672 and moved across to Ireland two years later to support William’s father’s career in the military. Congreve’s first portrait was made at the age of twelve whilst his family was in service to the Dukes of Ormond in Ireland. His education began at Kilkenny College and ended with a degree from Trinity College Dublin in 1686. The budding writer was already drafting short works and poems by the time he joined the Middle Temple to study Law in March 1691. His literary interests soon consumed his life and career, and brought him into the circle of the likes of Dryden whilst publishing his own lines.

On the verge of his blossoming literary career, and whilst writing to his friend Edward Porter in 1692, Congreve reflected on the landscape he found consolation in:

I have a little tried, what solitude and retirement can afford, which are here in perfection. I am now writing to you from before a black mountain nodding over me and a whole river in cascade falling so near me that even I can distinctly see it.

It is perhaps telling that the portrait on offer, as well as his likeness in the Kit-Cat series, depicts the writer in such a location.

Congreve’s five plays for the theatres of London explored the genres of satire and comedy to great effect. Despite their few in number, they quickly became some of the most popularly acclaimed pieces of dramatic arts in Restoration London. The predominance of Congreve’s female characters has been noted by scholars of the period. It was the actress Annie Bracegirdle who was to Congreve what Gertrude Lawrence was to Noel Coward. Bracegirdle was written into all of his leading female roles. Equally, the writer also attracted aristocratic patronage. He formed a close acquaintance with Henrietta, Lady Godolphin and later 2nd Duchess of Marlborough. Henrietta bore Congreve a daughter Mary, and was the main beneficiary in his will which included all of his jewels. Although often misquoted for Shakespeare, the following line has survived as the most perfect example of Congreve’s literary genius:

Heav'n has no Rage, like Love to Hatred turn'd,Nor Hell a Fury, like a Woman scorn'd.

Zara’s Speech, The Mourning Bride (1697)

The playwright eventually moved away from writing plays after the year 1700, often attributed to attacks his received and criticisms he received for his last serious play The Way of the World (1700). His commitment to theatre, however, continued. He collaborated with figures connected to musical theatre, including with the likes of composers John Eccles, John Weldon and Daniel Purcell. It was his collaboration with the architect Vanbrugh on the new Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket that secured his contemporary reputation.

Congreve never married and continued writing into his old age despite his failing vision and poor health. This included publishing editions of Dryden and translations of Moliere. In his last poem, written to his friend Lord Cobham less than a year before his death, he described his life:

retir'd without Regret,

Forgetting Care, or striving to forget;

In easy Contemplation soothing Time

With Morals much, and now and then with Rhime,

Not so robust in Body, as in Mind,

And always undejected, tho' declin'd …

Congreve died 19 January 1729 after sustaining internal injuries after his coach accidentally overturned the previous September. His body was interred in Westminster Abbey and attended by several members of the nobility. His memorial was carved after a portrait by Kneller and contains an epitaph written by the Duchess of Marlborough.

This fine portrait is in an excellent state of conservation and is ready to hang and enjoy in an early 19th century English gilded ‘Kneller’ style frame with large gadroons around the outside edge.

Final carousel image: White and black chalk study of William Congreve, Sir Godfrey Kneller. Courtauld Collection, London.

Higher resolution images on request. Worldwide shipping available.

Canvas: 31”x 37” / 79cm x 94cm. Frame: 42" x 48" / 107cm x 123cm.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato