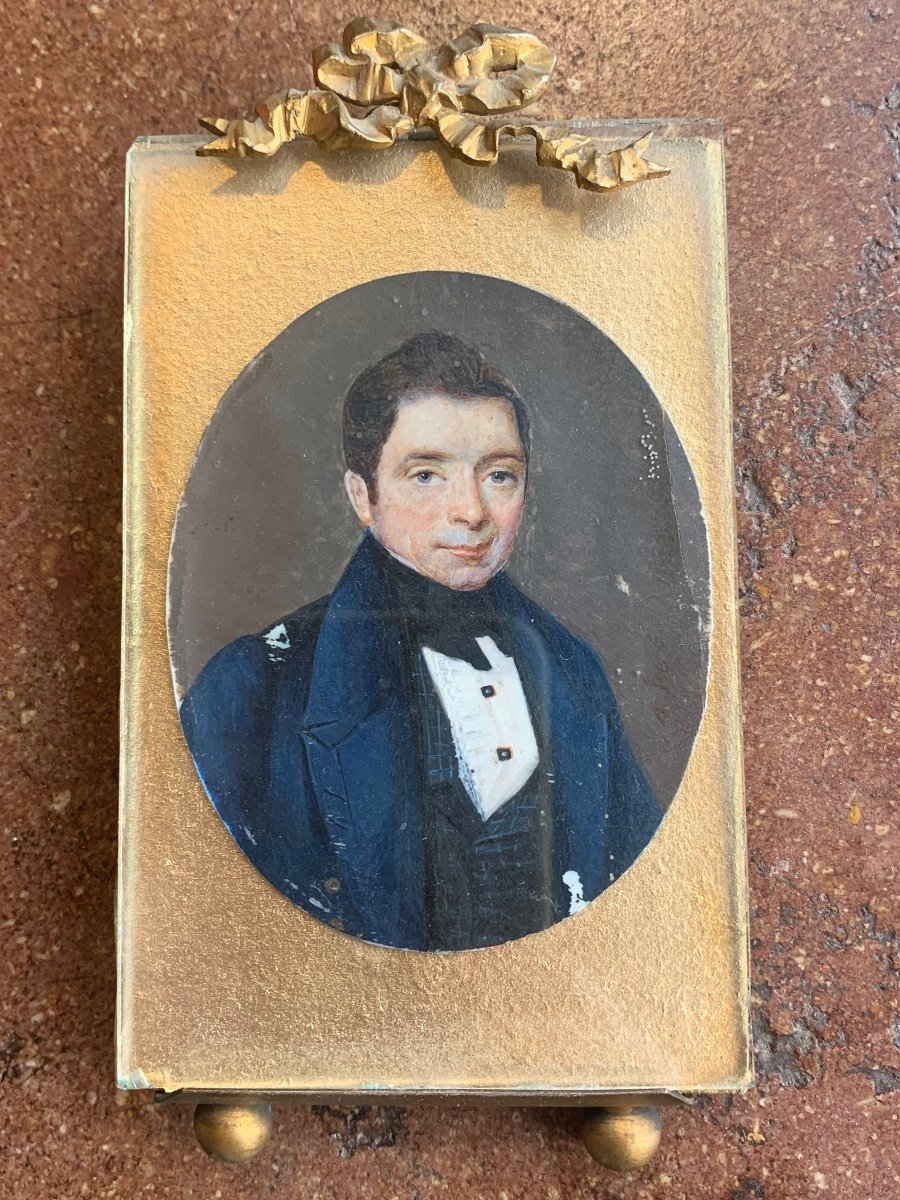

Gouache on an organic oval support.

There are small drops of color (visible in the photos).

Lined on the back with paper and cardboard.

The signature, partially legible, is located on the right side, placed vertically, with letters in light brown italic. Dated 1833.

To the right of the signature, in the marginal part, there is a slight fold in the support material on which the small portrait is painted.

In 1833, men of class tended to wear their hair short on the sides with more length on top.

The use of hair pomades or oils was common to keep the hairstyle in order throughout the day.

A black tie, not unlike those that might have adorned the necks of a Balzac or a Baudelaire, lies against a pleated shirt, whose buttons, like small lush gems, have diamonds set in black onyx.

In the year 1833, the male aristocracy adorned themselves with hairstyles sculpted with almost mathematical precision, short on the sides and longer at the top, as if each lock was a philosophical thought in the mind of Hegel. Pomades and oils were the tools to tame the mane, to maintain order in a world where order was everything.

The jacket, left open in a gesture of studied nonchalance, reveals a black vest, a textile abyss on which blue stripes dance to form squares, almost a Byzantine mosaic. The buttons, square and adamantine, are like seals of an unwritten pact of elegance and nobility.

And finally, the black scarf, tied with the precision of a ritual, an accessory that in 1830 was as much a declaration of fashion as of personal philosophy. A dandy of the time would have carefully chosen such an ornament, aware that every fold, every knot, every choice of fabric was a manifesto of self, a silent dialogue with the observer.

Set in a frame that belongs to a later era, this miniature portrait is a palimpsest, a visual text that tells of an era when clothing was a code, a form of art, an expression of one's position in the great narrative of society.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato