traces of laundry blue,

dolls were called "omolangidi" - "wooden child". They are carved rather simple and frequently they are made by an apprentice.

Young girls used to stick them into their clothes

as if they are babies, they are caressed, fed and decorated.

Just like in our culture, the young girls of the Yoruba in Nigeria use dolls, such as the present one, as ‘babies’ in mother-child role plays.

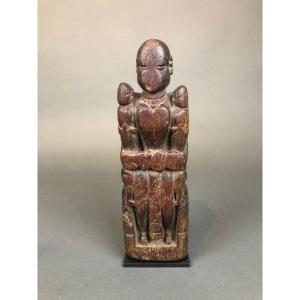

The present ‘Omolangidi doll’ made of dark brown, hard wood is especially beautiful and carefully manufactured. The head displays divided headress ,culminated by a ball carateritis of the Oyo style ; dyed with ‘bluing’. The face features the slightly protruding Yoruba eyes, the typical tribal decorative scarification marks on both cheeks, as well as an open mouth with two rows of teeth (with old traces revealing that the ‘baby’ was ‘fed’ by its owners!).

The flat, rectangular, slightly curved body of the doll shows a band of geometric, triangular chip-carving decorations on each side. Further ornaments of this ‘Omolangidi doll’ include red and glass glass pearl

A perfectly crafted object

provenance

Esquerre Toulouse

The heads range in form from highly abstract to very naturalistic.

The dolls are limbless with flat, generally rectangular torsos that allow them to rest comfortably against the child's back. According to Roslyn

Walker (1994:80), these dolls also cross functional boundaries: "In addition to being toys, omolangidi may also be used as substitutes for memorial figures representing deceased twins (ere ibeji). " The torsos of many figures are undecorated, while more elaborate examples may feature relief carving on one side.

A number of the latter depict rows of the writing tablets used to teach children Arabic and the Koran. The more abstract omolangidi are clearly derived from these writing tablets, their schematic shape undoubtedly an accommodation to the Islamic proscription against the representation of the human form.

Marylin Houlberg describes a similar simplification of form from the typical ibeji as an adaptation to both Islam and Christianity.

The writing-tablet shape as either a free-standing doll or as relief carving on a doll also emphasizes the value placed on the education of children in Yoruba society.

The heads range in form from highly abstract to very naturalistic.

The dolls are limbless with flat, generally rectangular torsos that allow them to rest comfortably against the child's back. According to Roslyn

Walker (1994:80), these dolls also cross functional boundaries: "In addition to being toys, omolangidi may also be used as substitutes for memorial figures representing deceased twins (ere ibeji). " The torsos of many figures are undecorated, while more elaborate examples may feature relief carving on one side.

A number of the latter depict rows of the writing tablets used to teach children Arabic and the Koran. The more abstract omolangidi are clearly derived from these writing tablets, their schematic shape undoubtedly an accommodation to the Islamic proscription against the representation of the human form.

Marylin Houlberg describes a similar simplification of form from the typical ibeji as an adaptation to both Islam and Christianity.

The writing-tablet shape as either a free-standing doll or as relief carving on a doll also emphasizes the value placed on the education of children in Yoruba society.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato