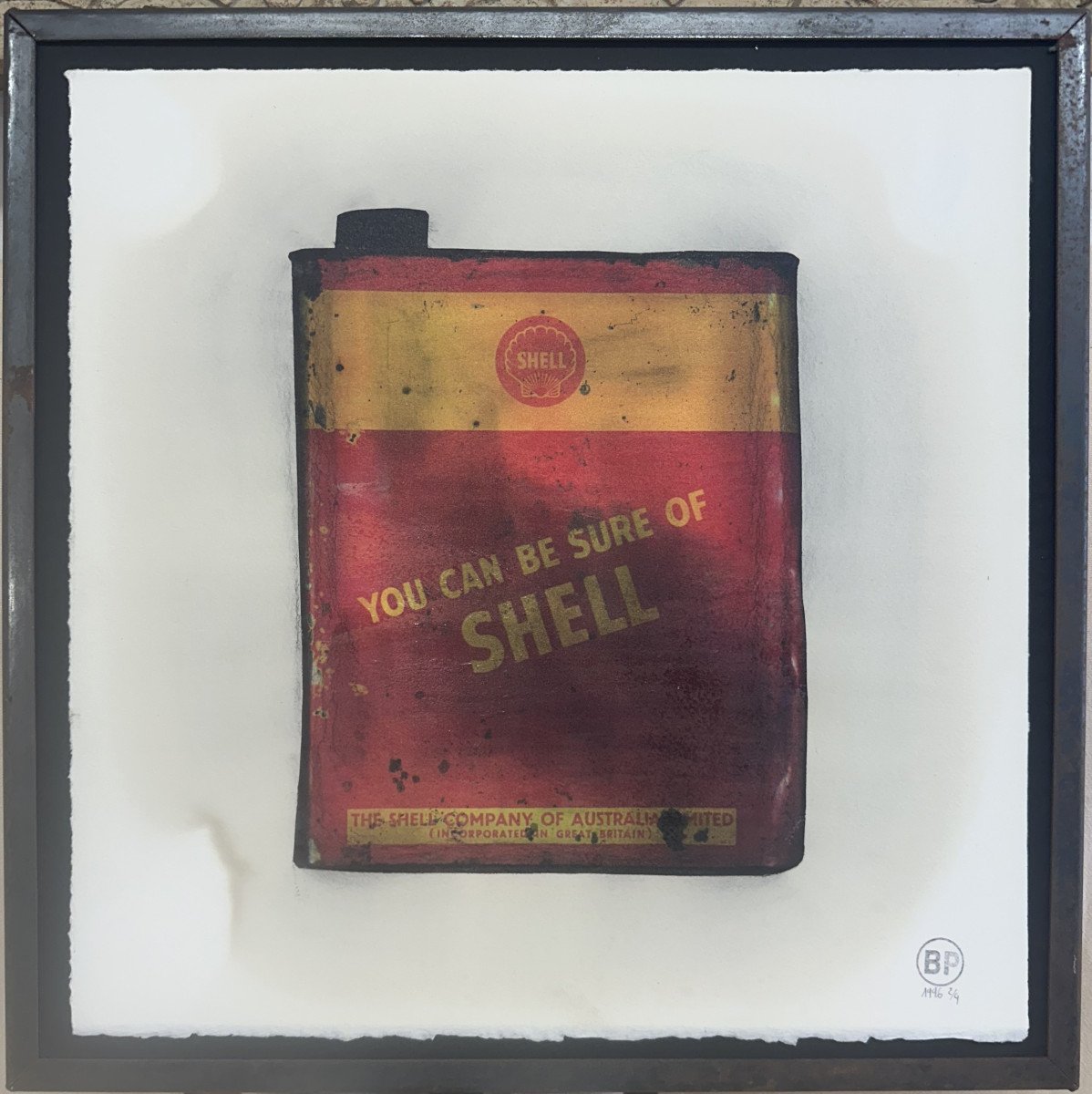

Richard Bellon, Renaud Layrac and Frédéric Pohl, all three students at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Nice, met in 1981. Shortly after, they decided to work together. This artistic collaboration became effective three years later, when they exhibited a first joint work entitled Monochromes. The three double glazing panels which form this room each contain the same quantity of engine oil with different characteristics. From this date, BP will be the generic name under which the three artists will appear. Obviously, the collusion which takes place quite quickly in the evolution of the group between an industrial material (waste oil), some accessories attached to it (metal drums, guardrails, fuel pumps, etc.) and an acronym uniting them does not fail to interest if only by a certain obvious deception and declined in a playful mode. In a perfectly referenced context, BP is also notable for the ambivalence it maintains with the brand of the multinational British Petroleum, in particular by regularly including the BP logo in its work. BP still intrigues with the very strict constraints that it has deliberately set for itself in order to enter the field of art. Today, even if the BP cell has separated from one of its members (Richard Bellon left the group in 1991), it remains faithful to its initial bet. Its plastic vocabulary revolves more than ever around the industrial ingredients on which the group has built its reputation. Used oil, seen as an advantageous substitute for paint, covers pieces of sheet metal recovered from damaged automobiles or is used to produce a screen on display cases in which are displayed rotating lights and mannequin heads usually used in accident tests. At first glance, his latest works are more openly oriented towards a dramatic background, although they maintain a close formal link with the previous ones, particularly in the creative process put in place by the group. Here is man facing machine. The human, or rather what he has become (the post-human), is reflected in the mirror of the used oil: a mannequin tests for him the dangers of his desire to go ever faster. Helmets and racing suits are erected as trophies, but when the oil covers them, the BP leaves doubt about the value of symbols in a world increasingly dehumanized by notions of competitiveness and technicality. The work of the BP reveals the machine body. We could almost smell a certain smell of burning flesh... The BPs place us face to face with a "State of the World" obsessed with the quest for oil, a humanity reduced to abstraction. The BP castigates the Promethean figure at its heart and as Cyril Jarton very rightly points out in the preface to the catalog “BP, Splash”, Louis Carré & Cie gallery, 2000: “Oil is the big manitou of contemporary life. Everything that rolls, flies, floats, heats, perfumes, dresses or is eaten is directly or indirectly linked to this bitumen juice, the most consumed on earth, after water. From Iran, where the first large-scale drilling began at the beginning of the century, through the oil shocks of 74 and 79, the Gulf War or the invasion of Chechnya, it is enough to follow the trajectory of the black gold to draw the map of modern evil. However, it was not until the mid-1980s that art, the analytical eye of society, recorded this evidence. Hacking the acronym of a well-known multinational, British Petroleum, a group of artists from Nice began a dive into the murky waters of the black order of hydrocarbons, a long-term investigation which would only logically cease with the exhaustion of the last oil deposit, the day when the nuclear state religion will definitively replace the refineries, these cathedrals of tubes, with their naves of gasoline and gas tanks enhanced by minarets with dark flames. Source; artists-in-dialogue.org

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato