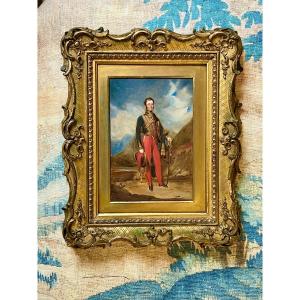

This gentleman is no doubt a man of high stature and rank as prominently perched inside his pocket is the sword which marks this gentleman’s noble status within society. This courtsword or in its French origin, known as ‘épée de cour’ meaning ‘sword of the court’ was a lighter and more agile variant of its heavier rapier predecessor from the Renaissance.

Significantly, the smallsword originated in France but soon engulfed the rest of Europe and solidified its high-fashion connotation. Government officials of the late 17th and 18th centuries would present them in their portraits to delineate their ruling power. Swords of this manner can also be found in portraits of other professions such as admirals and lieutenants.

Our sitter is adorned in the habit à la française that befits the Rococo aesthetic. The standout colours of the luxurious royal blue velvet coat and breeches combined with the golden embroidered waistcoat, coalesce to contrast the stone pilasters lining the background. Van Loo portrait backgrounds, tend to be hazed and less defined, allowing for full attention to the central subject. Due to this, our sitter’s features become more prominent such as their opulent laced jabot with the matching cuffs.

Nestled under the sitter’s left arm, is a tricorne or "cocked hat" as it was commonly known. Societal etiquette dictated that these hats would be tucked under one’s arm upon entering a building, as our gentleman perfectly demonstrates. The tricorne was also used as an accessory to show off one’s wig and by extension, their domineering social status.

Trendsetting in the 18th century was a gentlemanly vocation. The greatest innovations were from peruke (male wigs) styles, such as the adoption of the ‘bagwigs’. Bagwigs or ‘perruques en bourse’, were long and flat at the back and gathered at the nape of the neck into a black taffeta. It is clear this style was the vogue, as contemporary wig-technical publications such as “Perruquier" (appearing in Volume 12 of the Encyclopédie in December 1765) refer to the bagwig as "the most modern" of all.

These types of wigs were made by perukiers who would weave different types of hair such as goat or horsehair into wigs for gentlemen from the Georgian era. However, the more lavish wigs were made from real human hair and commanded a higher price for the material. Bagwigs typically gave a more formal appearance to the common wig; the addition of the silk bag and bow would allow the wearer to flaunt their wealth. Of course, there was an element of convenience to many 18th century perukes. It was commonplace for gentlemen to carry a tortoiseshell wig-comb in their pockets to ensure their wigs remained pristine throughout the day. However, the formal upkeep was done with relative ease which consisted of sending the wig to the perukier for the occasional delousing!

There are many hints of tradition and heritage in this portrait, namely our sitter’s signet ring. This piece of jewellery usually dons a heraldic motif on the fob seal and represents generational lineage. Its pertinence on his hand shows our sitter’s devout allegiance to his family. The coat of arms is embossed on what could be a sapphire or blue rock crystal. Our sitter is a man of great style, shown through the matching colours of his ring to his attire. To have the signet ring in full, central display and such proximity to the courtsword and tricorne hat, suggests our sitter is trying to communicate pride in his lineage, profession and personal accolades.

Jean-Baptiste van Loo spent five years in England between 1737-1742. He painted the likes of Sir Robert Walpole in the robes as Chancellor of the Exchequer, again indicative of van Loo’s tendencies to use semiotics to record his sitter’s profession and rank. I would however hazard that our sitter is French as portraits from the artist English period see the sitters sporting much longer wigs.

Jean-Baptiste van Loo (b. Aix en Provence d. Aix en Provence 1745) Van Loo was celebrated for his mythological, religious and portrait paintings. His talents were generational and multifaceted. The van Loo painting dynasty was inaugurated by Jean-Baptiste. His brother Carlé-Andre (1705-1765) and sons, Louis-Michel (1705-1771) and Charles-Ameedee-Philippe (1719-1795) all took up the painting profession. In turn, the van Loo familial enterprise does not fare well to the toils of authentication. Between them, their styles differentiated slightly in their paintings but there were distinct similarities between their drawings.

Jean-Baptiste was born in Aix-en-Provence and then studied under Benedetto Luti (1666-1724) in Rome under the patronage of the Prince of Carignan. Here, Jean-Baptiste was known to have painted churches. His talents saw him travel to Turin and paint Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy who later secured his appointment as painter to the Duke’s cousin, Victor Amadeus I, of Savoy, 3rd Prince of Cargnano (1690-1741). Upon his return to Paris in 1720, he became a member of the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture.

Van Loo ventured to England in 1737, it was here where he made an international name for himself, causing all who had their portrait painted by him to be in enviable positions.

His eventual return to France in 1743 was spurred on by a period of ill health, he was to die just three years later. His success as a societal portraitist in England, while short, was profound. Jean-Baptiste van Loo had a knack for precision and refining features, which was a skill born in France but truly nurtured on English soil. It was this artistry that proliferated high society in England, so much so that his popularity vexed Hogarth enough to turn his hand to portraiture out of spite. In fact, it was stipulated that van Loo’s favourability with Sir Robert Peel was so, that if it weren’t for an Act of Parliament preventing foreigners from having a salary in government, van Loo may have been in the rankings to be the King’s Painter!

Jean-Baptiste’s pièce de resistance was painting royalty and some of the most established members of parliament, this illustrious line of clientele was a testament to his credibility.

His adoration among 18th Century socialites was undeniable. Although our sitter has yet to be identified, it is a fine and brilliant addition to van Loo’s oeuvre of established gentlemanly portraits.

We are most grateful to Prfoessor David Sorkin with his help with this attribution.

Catalogue note: Charlote Askew.

Higher resolution images on request.

Worldwide shipping available.

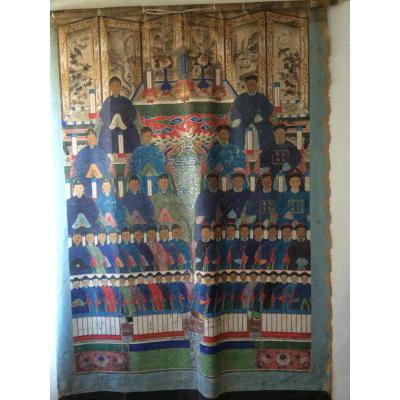

Canvas: 50” x 40" / 127cm x 102cm.

Frame: 60" x 50" / 153m x 127cm.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato