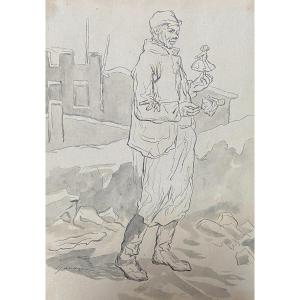

The Puppeteer, Study for "Janvier"

Signed lower left

Pen and black ink, black ink wash on paper

28 x 20 cm

In good condition except some stains particularly in the top two corners

Framed : 43 x 35.5 cm

This drawing should be compared with an engraved composition that was published three years after Gavarni's death, the month of January, "Janvier" in french, which was part of a set of twelve months: On 24 November 1866, Paul Gavarni died of a heart attack, in addtion to the various commissioned compositions he had in progress at the time of his death, he was working on ‘The Twelve Months’, a project for which he had already fixed the initial idea in sketch. Almost three years after the artist's death, the illustrator, who had had this series of figures transposed and engraved on wood, had this unfinished work printed, respecting the state in which each drawing had been.

If we compare our drawing with the final engraving (see photos), we can see a few differences, but most of the graphic content has been retained, including the inking, which shows the publisher's respect for the artist's work.

The details of the puppets are particularly charming, and the symbolism linked to the month of January reflects a very old tradition in which two elements are represented: the year that is coming to an end and the year that is beginning. The puppeteer lowers one and raises the other.

This work also bears particular witness to Gavarni's affection for and interest in the lower classes of society. The decor of a desolate suburb reduced to a few elements is also drawn with incredible modernity.

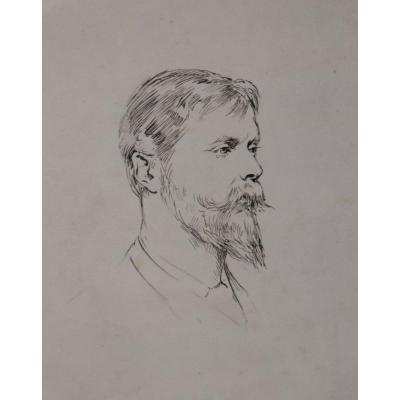

Paul Gavarni was the nom de plume of Sulpice Guillaume Chevalier (13 January 1804, Paris – 24 November 1866), a French illustrator, born in Paris.

The story is told that he took his name from Gavarnie in Luz-Saint-Sauveur where he had taken a journey into the Pyrenees.

His first published drawings were for the magazine Journal des modes.

At the time, Gavarni was barely thirty years of age. His sharp and witty drawings gave these generally commonplace and unartistic figures a life-likeness and an expression which soon won him a name in fashionable circles. He gradually gave greater attention to this more congenial work, and ultimately stopped working as an engineer to become the director of the journal Les Gens du monde.

Gavarni followed his interests, and began a series of lithographed sketches in which he portrayed the most striking characteristics, foibles and vices of the various classes of French society. The letterpress explanations attached to his drawings were short, but were forcible and humorous, if sometimes trivial, and were adapted to the particular subjects. At first he confined himself to the study of Parisian manners, more especially those of the Parisian youth.

Most of his best work appeared in Le Charivari.

Some of his most scathing and most earnest pictures, the fruit of a visit to London, appeared in L'Illustration. He also illustrated Honoré de Balzac's novels, and Eugène Sue's Wandering Jew

Among his illustrated works were Les Lorettes, Les Actrices, Les Coulisses, Les Fasizionables, Les Gentilshommes bourgeois, Les Artistes, Les Débardeurs, Clichy, Les Étudiants de Paris, Les Baliverneries parisiennes, Les Plaisirs champêtres, Les Bals masqués, Le Carnaval, Les Souvenirs du carnaval, Les Souvenirs du bal Chicard, La Vie des jeunes hommes, and Les Patois de Paris. He had now ceased to be director of Les Gens du monde; but he was engaged as ordinary caricaturist of Le Charivari, and, while making the fortune of the paper, he made his own. His name was exceedingly popular, and his illustrations for books were eagerly sought for by publishers.

A single frontispiece or vignette was sometimes enough to secure the sale of a new book. Always desiring to enlarge the field of his observations, Gavarni soon abandoned his once favorite topics. He no longer limited himself to such types as the lorette and the Parisian student, or to the description of the noisy and popular pleasures of the capital, but turned his mirror to the grotesque sides of family life and of humanity at large. Les Enfants terribles, Les Parents terribles,[Les Fourberies des femmes, La Politique des femmes, Les Mans vengs, Les Nuances du sentiment, Les Rives, Les Petits Jeux de société, Les Fetus Malheurs du bonheur, Les Impressions de ménage, Les Interjections, Les Traductions en langue vulgaire, Les Propos de Thomas Vireloque, etc., were composed at this time, and are his most elevated productions. But while showing the same power of irony as his former works, enhanced by a deeper insight into human nature, they generally bear the stamp of a bitter and even sometimes gloomy philosophy.

At one point Gavarni was imprisoned for debt in the debtors' prison of Clichy. After his release, he published his experiences in a work called L'Argent ("Money").

Gavarni visited England in 1849. On his return his impressions were published in the book Londres et les Anglais, illustrés par Gavarni (1862) by Émile de la Bédollière.

Most of these last compositions appeared in the weekly paper L'Illustration. In 1857 he published in one volume the series entitled Masques et visages, and in 1869, about two years after his death, his last artistic work, Les Douze Mois , was given to the world. Gavarni was much engaged, during the last period of his life, in scientific pursuits, and this fact must perhaps be connected with the great change which then took place in his manner as an artist. He sent several communications to the Académie des Sciences, and until his death on 23 November 1866 he was eagerly interested in the question of aerial navigation. It is said that he made experiments on a large scale with a view to find the means of directing balloons; but it seems that he was not so successful in this line as his fellow artist, the caricaturist and photographer, Nadar.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato