A Prodigy

Born in 1848 into a close-knit bourgeois family, Édouard Detaille, the eldest of eight children, displayed early talent in drawing. “He was a prodigy,” notes François Robichon. By the age of thirteen, he exhibited an astonishing surety of hand and a phenomenal sense of composition. His father, connected to Horace Vernet, encouraged him. At seventeen, after passing his baccalaureate, he entered Meissonier’s studio. This relationship, which developed into mutual affection, spared Detaille the academic detour through the École des Beaux-Arts. Rather than dictating an official art style, Meissonier, at the peak of his fame, traveled with his students, introducing them to the nuances of Titian, Rembrandt, and Rubens in Brussels and Lille.

In 1867, the Paris of “free trade” dominated the world through the technological revolutions of the Universal Exhibition, and the amiable young man, striking in appearance, discovered the salon of Princess Mathilde and the theater of Dumas fils. He even approached the Empress, noting in his journals, “Not bad, the Empress.” This observation encapsulated Detaille: he had no doubts about his talent, cultivated panache, enjoyed the company of beautiful women, and aimed to conquer the circles of power without sacrificing his freedom.

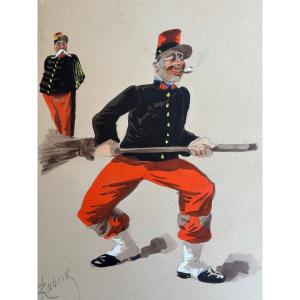

From childhood, he listened to his calling: “Before I could read, I could guess the subjects of battles, the names of famous generals, the weapons of officers and soldiers from the images I admired in the books of Norvins and Laurent de l'Ardèche.” He mingled with collectors and regularly attended military reviews on the Champs-Élysées. His first painting exhibited at the Salon in 1868, “La Halte de tambours,” was praised by critics who immediately recognized “a remarkable truth of observation and simplicity of effect.” The purchase of this work by Princess Mathilde, cousin of Emperor Louis-Napoleon, made Detaille, at twenty, an envied celebrity known to Sainte-Beuve, Théophile Gautier, the Goncourt brothers, and Flaubert. The young artist’s humanistic vision contrasted with the compositions of his predecessors, depicting soldiers in maneuvers, contemplative and resigned as war loomed.

The Combatant’s Vision

The Siege of Paris, where he nearly lost his life in 1870, and the deaths of two brothers in that defeat darkened his outlook. From 1871 onward, Detaille no longer concealed the cruelties of war: German riflemen mowed down by machine gun fire, cavalrymen and panicked horses caught in ambushes, fields plowed by shells strewn with dead animals. The unvarnished tragedy: “It is an absolute fact that no painter has ever rendered a battlefield covered with corpses as it is,” commented Jules Claretie. The fallen bodies still bear the appearance of life in their frozen rigidity. Detaille’s testimony of the devastating defeat and the catastrophic effects of the first total war in history was not a celebration of heroism but a lament, a “lesson in darkness.” “From war, once considered the supreme effort of human genius, we now see only melancholy and horrors,” judged one writer in response to his canvases.

“Detaille experienced the reality of combat at a young age during a war that foreshadowed the two world conflicts of the 20th century,” explains François Robichon. With great realism, Detaille painted war from the perspective of the combatant. He introduced a humanity and a critical lucidity regarding the evolution of warfare. His works intensely captured the violence and firepower of new weapons like machine guns. Before he turned thirty, Detaille had become a chronicler of these painful years. He exhibited, as a critic noted, a “striking portrait of modern war” that both French civilians and soldiers had experienced firsthand. He embodied a youth humiliated and eager for revenge. Yet this scrupulous artist also remembered, in his expansive landscapes—from the chalky plateaus of Île-de-France to the Russian plains—the lessons of Corot and Courbet. Manet was not far off. “I wouldn’t want my art to be reduced to mere patriotic art,” he asserted. “A system I often employ and love is to first execute the landscape, very effective, very tight, based on nature…” Echoing Meissonier’s advice: “Always nature, always nature!” Detaille remained close to this father figure, constructing a grand townhouse next to his mentor’s studio at 129 boulevard Malesherbes at the age of 26, having purchased 425 m² of land from the Pereire brothers. He even chose the same architect as Meissonier: Paul Boesvilwald. A bachelor and incorrigible seducer, the painter welcomed his conquests, including Valtesse de la Bigne, amidst his collections, having built his studio in the courtyard.

Diplomatic Actor

As Detaille’s fame grew, his Malesherbes townhouse quickly became a gathering place for foreign princes, politicians, and heads of state, where Juliette Adam, Léon Gambetta’s muse, offered him valuable advice. The Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, developed a genuine friendship with the painter. “This fervent patriot, friend of Déroulède, was extraordinarily open to the world,” recounts François Robichon. In just a few years, he gained considerable social, cultural, and international stature. Received at Windsor, at the English court, he was close to Tsar Alexander III and a great friend of Félix Faure.

In this capacity, Detaille played a decisive role in the Entente Cordiale, signed in 1904 between England and France, and in the Franco-Russian alliance of 1894, thereby contributing to the Triple Entente among the three powers. An engaged witness of his time—associated with the birth of the “Ligue des Patriotes” alongside Alphonse de Neuville and Déroulède, founder of the “Sabretache,” and initiator of the Army Museum—Detaille was not blinded by his convictions. He was not indifferent to the honors discreetly paid to him by Wilhelm II and the Crown Prince through diplomatic channels. Like Barrès, he placed his hopes in the restoration of a symbol tarnished by Sedan: the French army.

Beyond this choice, he was a man turned towards modernity. “Well-informed from the best sources, he was at the center of European life,” observes François Robichon. Knowledgeable of photography’s potential, he was among the first in the 17th arrondissement to install electricity and telephone, to drive a car, and to attend the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph sessions in 1896. He even contemplated making a historical film. In this sense, he was a precursor. His astonishing war panoramas—Champigny and Rezonville—long sequence shots created with Alphonse de Neuville on rue de Saussure, near the Asnières gate, anticipated the historical cinema of Abel Gance, the naturalism of John Ford, the frescoes of Andrei Tarkovsky, and the emotional power of Apocalypse Now. Did Abel Gance not draw his Napoleonic epic vein from Detaille’s paintings? Detaille imagined a painting beyond the frame, capturing both the entirety and detail of the cathartic upheaval of war. He pushed the traditional boundaries of his profession, paving the way for the major art of the 20th century: cinema.

Detaille passed away on December 24, 1912, at his home on boulevard Malesherbes, and his funeral was nearly a national event, held at Saint-Charles-de-Monceau church on December 27. A company from the 28th infantry regiment, for whom he had designed the new uniform, presented arms. The Prime Minister, Raymond Poincaré, bareheaded, walked behind the family. Today, François Robichon, who has sensitively and passionately revived the painter's fate, is fighting to save his grave at Père Lachaise.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato