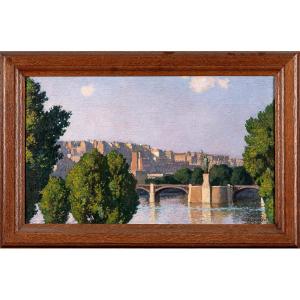

These words by Louis Henaut, published in Paris Salon in 1882, well reflect the admiration of critics and the public for Ségé. Arsène Houssaye in L'Artiste highlighted the painter's talent in 1877. Trying to define his nature, he stated: "[He] is never wrong about the range of skies, waters, trees and grasses. He penetrates their intimate harmony."

By setting up his easel in the salt meadows of the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel, Alexandre Ségé confirms these words. It is a land he knows well, since he discovered neighboring Brittany at the age of twenty. He spent a long time on the Emerald Coast, a few kilometers from Mont-Saint-Michel. As with his Beauceron paintings, Ségé makes the characteristic silhouette of the country emerge from the depths of a vast expanse. In Chartres, it was the two spires of the cathedral that could be seen emerging above the ploughed fields. Here, it is the medieval abbey that punctuates the composition. Cutting short the debate between impressionism and academicism, Ségé offers a new form of landscape that could be described here as synthetic.

Still picturesque, but already attached to the effects of fragmented light, Alexandre Ségé is an avant-garde figure. Mont-Saint-Michel benefited from a considerable revival of interest during the second half of the 19th century. Listed as a historic monument in 1862, the abbey was topped with a spire in 1889. This spire, naturally invisible in our painting, was itself topped with the archangel of Fremiet in 1897. Today, the place is the most visited in France outside of the Ile-de-France.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato