Studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723)

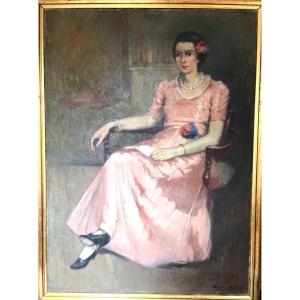

This elegant and beautiful portrait depicts Abigail Hay, Lady Dupplin, Countess of Kinnoull; it is an excellent example of English portraiture from the first quarter of the seventeenth century. Beautifully composed, the sitter has been depicted three-quarter length and seated on a porch beside a crown on a ledge. She is wearing peeress’s robes - a scarlet ermine trimmed robe and a luxurious silver dress with gold thread. It is the archetypal example of portrait what the titled class in England wanted; the format was reproduced many times by Kneller and his contemporaries and these portraits lined the walls of many great halls in stately manors throughout the Britain.

Born Lady Abigail Harley, she was the youngest daughter of Robert Harley, 1st earl of Oxford, (1661-1724), chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Treasurer to Queen Anne, and Elizabeth Foley (died 1691). Her siblings were Edward (1689-1741), Elizabeth (1689-1713), and Robert (who died in infancy in 1690). She was brought up at Brampton Bryan Hall.

On 11th August 1709 she married George Henry Hay, 8th Earl of Kinnoull (1689-1758), styled as Viscount Dupplin from 1709 to 1719. Her husband had come under the wing of her father, whose position was equal to that of prime minister. This led to Hay’s seat in the Commons and ultimately his peerage. After her marriage she was styled as Lady Abigail Dupplin and from 5th January 1719, Countess of Kinnoull. The couple had four sons and six daughters between 1710 and 1723.

Lady Abigail seems to have inspired the affection of those who knew her. One visitor to the Kinnoull family seat, Dupplin House, in Perthshire, described her as ‘the fine lady who is mistress of it, at the head of her family of most delicate children.”’ Lady Abigail’s letters show her to be a fond and caring parent.

Dupplin House was too far from the centre of political life and shortly after their first child Thomas was born in 1710, the couple left on a house-hunting expedition to London. The baby was entrusted to Sir Patrick Murray of Ochtertyre, an old family friend, and his wife, who received frequent letters from Abigail, inquiring after Thomas’s health: “I’m extremely glad to hear my dear little boy is so well and takes to his feet. ... I long to see my dear Child. I dream of him every night; Pray remember me to nurse ... tell her I heartily rejoice y' her Master has a tooth ... pray let me know if his tooth be on the upper or lower side.”

In the early years Lady Abigail expressed her satisfaction with married life: in connection with her brother’s marriage, she wrote: ‘I hope he will make as good a Husband as my Lord Dupplin. I need say no more to commend him.” As a young man George Hay seemed destined for a successful career. With Harley’s help,’ he became the member of parliament for Fowey in 1710, aged 21.

In addition to his Scottish title, George Hay was granted the title of Baron Hay of Pedwardine in 1711. Hay was a classical scholar and William Bromley wrote at the time of Dupplin's acceptance of the post that Dupplin was "such a handsome man, and so universally loved." In 1712 Viscount Dupplin was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. However, his pollical career suffered when Harley resigned from the post of Lord High Treasurer a few days before the death of Queen Anne. With this, Lord and Lady Dupplin relocated to the country and purchased Brodsworth House in Yorkshire in 1713 and this became the centre of family life for Abigail and her children, writing to her aunt: “Thank God that I can live here with so much satisfaction and delight.”

However, unfortunately for him and for the family, in 1715 he was arrested, along with others, including his own father, and imprisoned in the Tower of London on suspicion of having been involved in the Jacobite rising of that year. This was not surprising because his younger brother, John Hay of Cromlix, was deeply involved, as was the Earl of Mar whose late wife Margaret had been the sister of George and John Hay. Dupplin was in due course formally cleared in 1717 and returned to Brodsworth. In the four years following this, Dupplin appears to have spent much time in Yorkshire attending to his new estate. Abigail wrote that ‘never any one was so full of business now as he is between the stables, garden and hay makers he is never in the house in daylight but to eat his dinner.” However, they spent time in London too as Wimpole, who evidently knew the Dupplins well, wrote on 10th September 1718: ‘Little Tommy Haye has the smallpox of a very good kind and is likely to do well’ and, by 29 September 1718, ‘little Dup is perfectly recovered’.

Dupplin succeeded to the title of Earl of Kinnoull on the death of his father in 1719 - from whence Lady Dupplin was styled as Countess of Kinnoull – and inherited Dupplin House. On occasion Lady Abigail was left at Dupplin House with the children while her husband remained in London. She asked her brother Edward to write to her often: ‘It is charity now I am so far from all my friends”. However, her loyalty to her husband was unswerving. She wrote from Edinburgh, in 1721, that the place was dull, but ‘I have so much of my Lords company for he is almost always at home & that makes any place agreeable.’"

By 1720, the new Lord Kinnoull was spending much time in London again. Harley, his father-in-law, had been chief founder or regulator of the South Sea Company and its governor from 1711; Kinnoull was appointed commissioner for taking subscriptions to the Company in that year.’ Kinnoull wrote to Harley that: ‘I hope to make such profit in the South Sea Stock as to make the Dear Children’s provision very easie & yr. Daughter’s Comfort & the Care of those Dear Babies being my Greatest Concern in this World”.

On 16 May 1729, he was appointed British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire; Kinnoull himself stated that his appointment was due to the patronage of William Cavendish, second Duke of Devonshire, where ‘that Great person, who as he was a father to me, was likewise a true friend and support’. He and his eldest son left England in 1729 and arrived at Constantinople the following year, and then left Turkey in the fall of 1736. He died at Ashford in Surrey, 28 July 1758 and was succeeded by his son Thomas.

Abigail died on 18th July 1750 and was buried in the Saint Michael and All Angels Churchyard at Brodsworth, England.

The work is held in an exquisite Queen Anne bolection style gilded frame with presentation label – an impressive work of art in itself. This style first came into use during the end of William III and Mary II's reign and was at the height of fashion during the reign of Queen Anne (1665-1714) and continued through George I's (1660-1727) reign. It is easily recognised by its gadrooned knull and ornamented sight and back edges.

All of our paintings pass a strict quality and condition assessment by a professional conservator restorer prior to going on sale. As such they can be hung and enjoyed immediately.

Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) was one of the most prominent portrait painters in England at the end of the seventeenth century. He painted seven British monarchs (Charles II, James II, William III, Mary II, Anne, George I and George II) and in 1715 was the first artist to be made a Baronet (the next was John Everett Millais in 1885).

He was born in Germany but trained in Amsterdam and studied in Italy before moving to England in 1676. Towards the end of the century, after the deaths of Peter Lely and John Riley, Kneller became the leading portrait painter in Britain and the court painter to English and British monarchs from Charles II to George I. He dominated English art for more than thirty years. His over 40 "Kit-cat portraits" and the ten "beauties" of the court of William III are most noteworthy. He ran a large, busy and successful studio in London and employed many assistants thereby establishing a routine that enabled a great number of works to be produced. His name became synonymous with British portraiture at the time and he rose to great notoriety; and there were countless other artists that strove to emulate his style. He died of a fever in London in 1723 and a memorial was erected in Westminster Abbey.

In Kneller’s will he left 500 unfinished pictures to his chief assistant Edward Byng (c.1676-1753) who in Kneller’s words had "for many years faithfully served me". Byng lived with him at a house in Great Queen Street. Kneller gave him a pension of £100 a year, and entrusted him to complete these pictures, for which he was to receive the payments for them. Kneller had been paid only by half for these; whether his clients were not as expeditious to pay as they were to sit or whether Kneller’s death came first, the reason being unknown. Byng also inherited drawings in Kneller's studio, many now in the British Museum. He later lived at Potterne, near Devizes, where he died in 1753 and was buried. His brother Robert was also a painter and many works have been jointly attributed to both brothers. According to Edward’s will his estate was divided after his sister Elizabeth's death between his nephew’s William Wray, Robert Bateman Wray and Charles Wray (not, as some have suggested, to Robert Bateman Wray and his sister Mary).

Provenance:

From the sitter to her second son;

Robert Hay Drummond (1711-1776), later Archbishop of York, to his eldest son;

Robert Auriol Hay-Drummond, 10th Earl of Kinnoull (1751-1804);

Thomas Robert Hay-Drummond, 11th Earl of Kinnoull (1785-1866);

Captain Hon. Robert Hay-Drummond (1831–1855), to his brother;

Captain Hon. Arthur Hay-Drummond (1833–1900) (succeeded to Cromlix in 1855), to his brother;

Col Hon Charles Rowley Hay-Drummond (1836-1918), to his son;

Colonel Arthur William Henry Hay-Drummond of Cromlix (1862-1953), to his daughter;

Evelyn Vane Hay-Drummond (1904-1971), who married her cousin in 1925 Terence [Eden], 8th Baron Auckland;

(Probably) circa 1971 when the Eden family (descendants of Hay-Drummond’s) sold Cromlix House

Measurements:

Height 145cm, Width 120cm, Depth 6cm framed (Height 57”, Width 47.25”, Height 2.5” framed)

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato