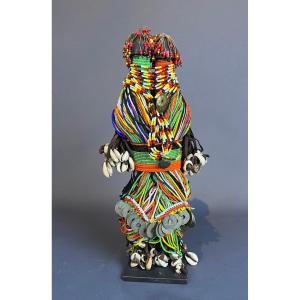

The dhodro banam is played with a bow like a violin, but in a vertical position and the sculpture on the top is always turned towards the listener. The Santals play this generally single-stringed instrument to accompany their songs and dances like the Dasae, Sohrae, Don, Lagre and Karam. Given the nature of the form, the Santals believe that the instrument is a human being (or the long lost sister with a tragic fate) and that it possessed the power to connect the world with other supernatural realms. Surviving examples are carved from a hard wood, although myth mentions the Champa tree which is a rather softer material. Dr. Verrier Elwin, a noted anthropologist, in his book The Tribal Art of Middle India, reports that a heavy wood, particularly Grewia tiliaefolia, was used for these instruments and the surface was blackened with oil. Sculpted on all sides, the sound box was covered in lizard skin (Land Monitor). The rope, most of it unique, was made from the intestines of a goat.provenance This very beautiful instrument was collected in situ by Joachim Pecci in the early 1980s. Acquired from the precedent by Pierre and Ruth Denhaive Summary of the article by philippeBourgoin https://philippebourgoinarttribal.com/2014/10/31/a-cordes-et-a-corps-instruments-de-musique-de-linde/:l “In November 2013, the Museum Rietberg in Zurich was able to acquire the important collection of stringed instruments by the famous German illustrator and advertising graphic designer Bengt Fosshag. The Santals, the largest group of the Munda people, live mainly from rice cultivation. They live in Bihar, Orissa and West Bengal social and cultural pressures exerted by the dominant Hindu population The dhodro banam is a simple instrument - in general, it has only one string - whose archaic appearance suggests that it would be the precursor of the sarinda. The Indian musicologist Onkar Prasad (Santal Music, New Delhi, 1985) considers the dhodro banam as a regressive form of the sarinda. The musician holds the dhodro banam vertically in front of him, the neck and the hand that plucks the string above and the hand holding the bow below

In terms of the differences of the dhodro banam: a long body which is not curved like that of the sarinda; an open part separated from the part covered with skin by a step which makes a more or less continuous transition and not by a lateral indentation "wasp waist" Two other characteristics of the dhodro banam underline the particular development of this instrument. First of all, it is played in a different way from sarinda: it is the internal surface of the extended fingers which presses the string. Then, the sculpture surmounting the dhodro banam faces the audience while the figures adorning the pegboard of the sarinda are only identifiable when seen from the side. Which implies autonomous artistic development. With the exception of the constants of the elongated body and the rectangular anklet, the appearance of the dhodro banam is very variable. The “shoulders” of the instrument can be flat, laterally stretched, or rounded. It can happen that extensions of the handle protrude on the open part of the body and different formative elements, part of the bridge, can be found there, sometimes with an anthropomorphic shape. The transition between the open part of the body is continuous in some instruments and, in others, clearly discernible as a separation. The handle can also be presented in different aspects: square, completely rounded, or even rounded with a vertical plane.Some examples show a handle hollowed out from the back or on the sides; the handle can even, in certain rare cases, be formed of four columns. Figurative representations crowning stringed instruments are frequently observed in India, mainly in the east and in the Himalayas. Animals are the main motifs, especially birds, but also horses, goats, fabulous animals and, sometimes, groups of animals and humans. In eastern India, the peacock is particularly prized. The Santals prefer human figures. Animals are usually present, but in a secondary position, for example ridden by men A sandalwood myth, related by the musician

Onkar Prasad (Santal Music, New Delhi, 1985), tells us the story of seven brothers who killed their only sister to eat her. However, the youngest, who adored his sister, could not swallow the piece that was his. He buried it in a white anthill and, in this place, grew a magnificent “guloic” tree which let out a melodious sound. A yogi who often came to pick flowers there heard this melody and cut one of its branches to make the first dhodro banam. Prasad mentions that the Santals believe that this musical instrument is a gift from supernatural forces. With its assistance, they can communicate with entities inhabiting other worlds.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato