(Plymouth, 1794 –Baden-Baden, 1853)

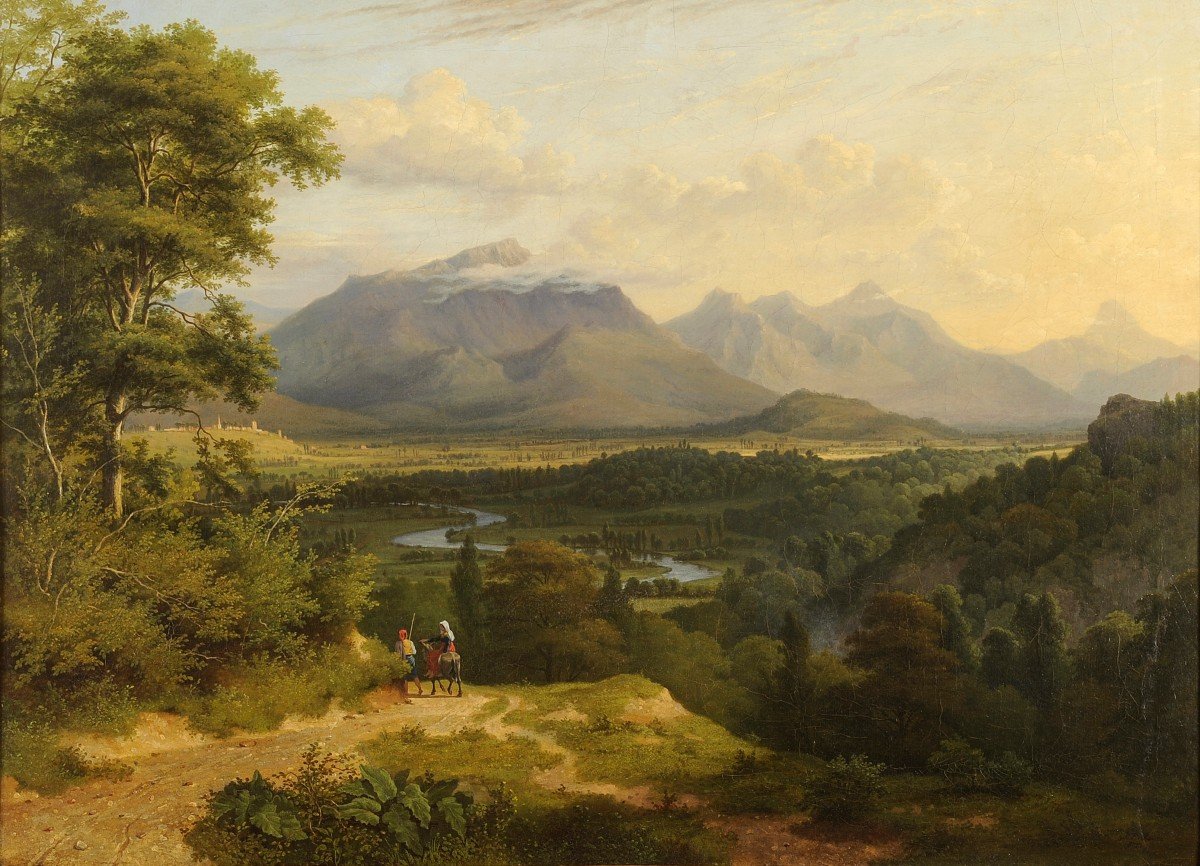

View of Italy

Oil on canvas

H. 66 cm W. 95 cm

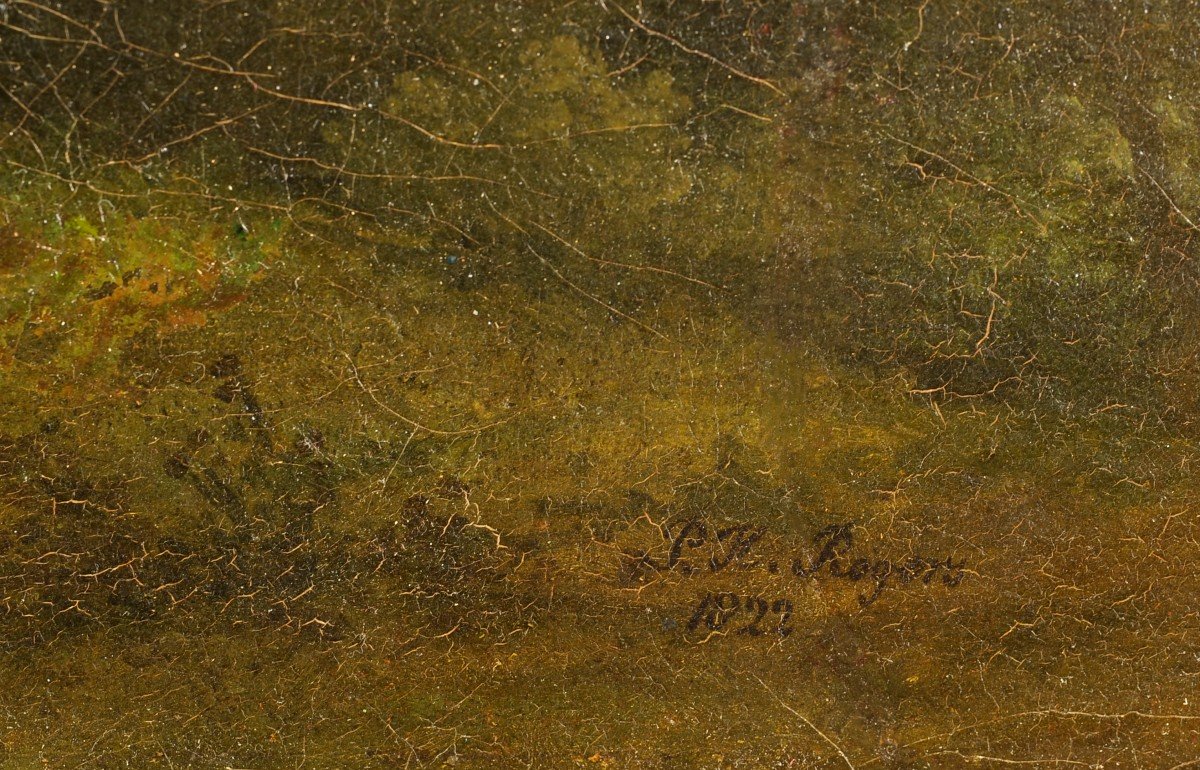

Signed lower right and dated 1822

After the fall of Napoleon and the end of the continental blockade, the English were legion to rush to France to renew with the practice of the continental tour. Since the mountains had become a privileged category of the aesthetic of the "sublime", many British painters traveled the Alps or, in smaller numbers, the Pyrenees, to draw the views that would serve them to compose paintings or lithographs. At the end of the 18th century, the painter Archibald Robertson had already exhibited Pyrenean sites at the Royal Academy. One of the first artists from across the Channel to explore the Pyrenees during the Restoration was Marianne Coltson, who stayed between Bayonne and Luchon in 1820 and produced a collection of engravings. Also a pioneer of the Pyrenean sketching tour, Philip Hutchins Rogers visited the eastern part of the massif, towards Ariège and Catalonia, in the same year before going to Spain. The memories of his trip were to provide him with the subjects for his first paintings presented at the Royal Academy. In 1821 he showed: Remains of an old castle in one of the valleys of the Pyrenees, Catalonia, from a sketch made on the spot in July 1820; in 1825: Pamiers, a town in the confines of the Pyrenees; and in 1833: Le Château de Foix (in French in the catalogue). Painter of landscapes and seascapes, Philip Hutchins Rogers was born in Plymouth where he trained with John Bidlake, in the company of Samuel Prout, Benjamin Haydon and Charles Lock Eastlake. Then his master paid for his studies in London where he benefited from famous patronages, such as those of Reynolds and Turner. He would end his life in Germany where he would settle from 1839. In 1822, Rogers was perhaps still in Italy where he went after his stay in France. Did he create this canvas on site from a few sketches, or was it an idealized work created in London? The painter gives a magnificent breadth to this landscape where the green valley, with its successive planes, its variations of light and chromatic intensity, the blue arabesque of a river, counts just as much as the mountains camped in the background of the decor. The touch is as subtle and meticulous as that of the French who composed historical landscapes. But to the mythological fictions which served as a pretext for the latter, the English prefer the simple exaltation of a grandiose nature.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato