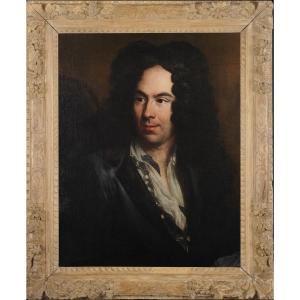

Portrait of Cardinal Mazarin - Sketch

Oil on canvas

H. 41.5 cm; W. 27 cm

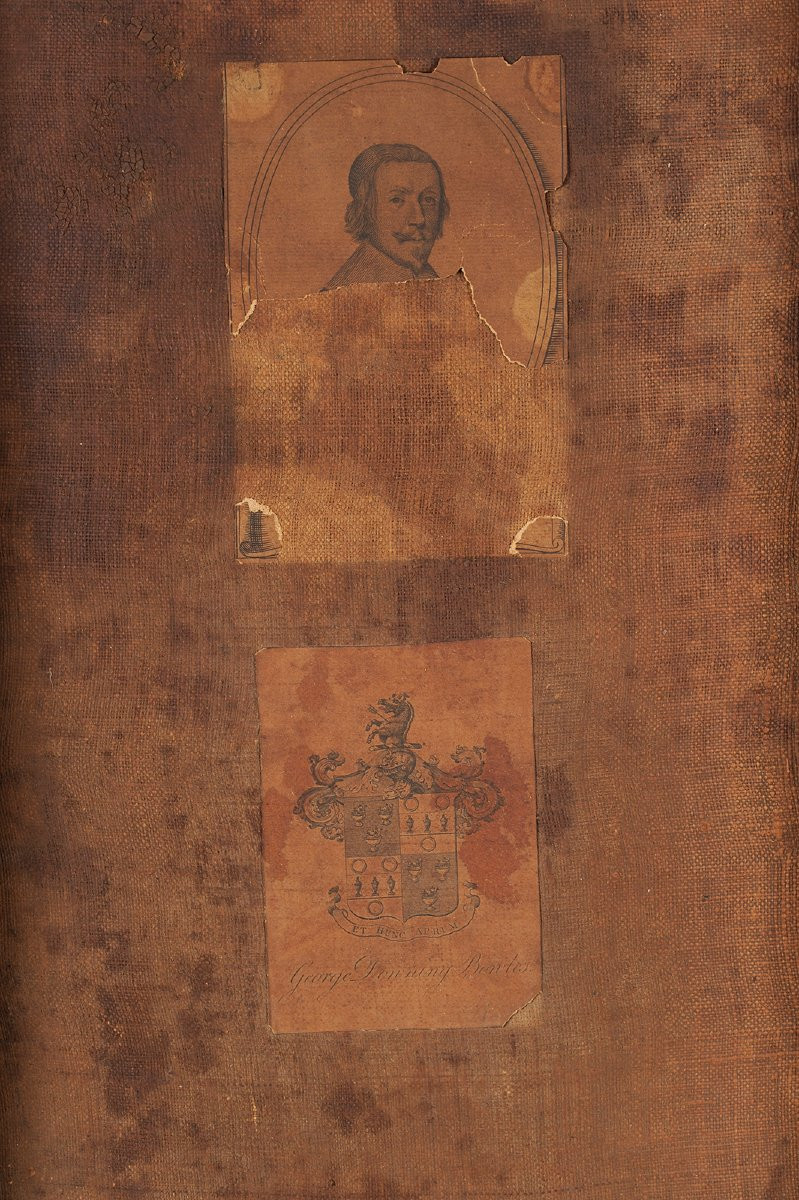

Provenance: Collection of the Reverend Georges Downing Bowles (1789-1863)

Would the Grand Siècle have been so great without the action of this Italian renowned for his political finesse, his outrageous enrichment and his fabulous collection, but whose tenacity, talents as a war leader and unfailing devotion to a State that was not his are often forgotten? In one of the most troubled periods in our history, Giulio Raimondo Mazzarini (Pescina, Abruzzo, 1602– Vincennes, 1661), who became Cardinal Mazarin, was able to restore the power of France against the Habsburgs of Spain and Austria, and defend the throne of the young king whose godfather he was against the machinations of the high aristocracy and the parliaments. Our sketch does not correspond to any of the works known to date representing Mazarin. However, it prefigures an ambitious and, to say the least, solemn portrait. Mazarin, - whose features, although suggested, are easily identifiable -, poses here as a statesman more than a man of the Church. His voluminous scarlet silk cloak (the cappa magna), a billowing flow of fabric bubbling with complex folds, enriched with an ermine hood, redoubles its importance and erects it as a monument to power. Regarding Champaigne's portraits of Richelieu, Bernard Dorival noted that it was extremely rare for a prelate to be depicted standing: the seated position was the dominant convention at the beginning of the 17th century. Our bozzetto adopts the majestic formula used by Champaigne to paint Richelieu full-length. It even reproduces the detail of the cardinal's left hand pulling up his cope to reveal the white of his robe (a detail visible on a preparatory red chalk preserved at the BNF and in the version belonging to the National Gallery). The decoration is of the same type: heavy hangings, columns and balustrade opening onto a garden. However, Champaigne's Richelieu occupies almost entirely the space of his portraits, while our Mazarin is somewhat lost in the height of his palace. On the other hand, while Richelieu holds a barrette, Mazarin, in his right hand, ostentatiously presents a medallion depicting the frail silhouette of a crowned king, that of Louis XIV, called to reign at the age of fourteen. On a console are placed a geographical map, disparate notebooks, - perhaps the famous small notebooks used daily by the cardinal, although they do not resemble those preserved by the BNF -, as well as other miniatures. So many distinctive signs of a strategic minister proclaiming his loyalty to the king, more than of a minister of the faith. We note the presence of an imposing gilded console with a heavy scrolled base. This rich console, combined with the majesty of the pose and the cardinal's purple, serves to stage a power that has reached its zenith. If our bozzetto had resulted in a painting, it would have displayed a far greater pomp than the portraits known today. Mazarin could have had this sumptuous Baroque piece of furniture, which occupies a large space in the composition, imported from Italy. But based on a hunch by Jean-Claude Boyer, another hypothesis presents itself, which would explain the console: could our portrait project not be by an Italian hand, perhaps painted at the request of some member of Mazarin's family, anxious to honor the uncle who had made the fortune of the dynasty? It could, as such, be slightly retrospective. Unless it was a commission interrupted by the cardinal's death. Or perhaps the aborted attempt of a courtier painter anxious to position himself? So many questions, along with that of its attribution, that we will leave open while awaiting new elements. For the moment, we offer a rare testimony on the statesman who allowed the advent of the reign of Louis XIV. An element of provenance is indicated to us thanks to a collection label affixed to the back. This bears the arms of the Reverend Georges Downing Bowles, who died in London in 1863 and who owned a fairly large collection of portraits of illustrious men. Nearly thirty works from this collection were bequeathed by the reverend in 1850 to the Worcestershire Museum. We find there portraits of English and French kings, portraits of philosophers such as Erasmus, etc. Our canvas, considered at the time to be a portrait of Richelieu (as evidenced by the rest of the engraving on the back of the work), has left no trace as to its journey to reach us today.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato