IRREGULAR COSSACK DRESSED IN RAGS OF A WOMAN HE HAS PLUNDERED

ALEXANDER SAUERWEID

Courland 1783 – 1844 Saint Petersburg

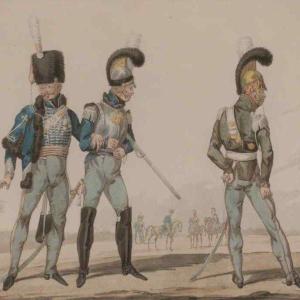

Hand-colored aquatint on paper, signed “Sauerweid del.”, “Jazet sculp.” and in the center "Cosaque irrégulier vêtu de hardes de femme qu'il a pillées."

17 x 17.5 cm / 6.7 x 6.9 in, with sheet 21 x 26.5 cm / 8.3 x 10.4 in

PROVENANCE

Private collection, Vienna

BATTLE SCENES IN POST-NAPOLEONIC PRINT CULTURE

In the years following the fall of Napoleon in 1815, Europe witnessed not only a redrawing of its political map but also a surge in public appetite for images that reflected the drama, trauma, and spectacle of the Napoleonic wars. One of the most fertile arenas for this visual culture was the medium of printed graphics — especially aquatints and lithographs — which allowed for wide dissemination of military subjects to a growing bourgeois audience.

Among the many artists and publishers active in this context, the collaboration between Alexander Sauerweid and Jean-Pierre-Marie Jazet stands out as a compelling example of cross-cultural image-making. Sauerweid, a Baltic German painter who settled in Russia and rose to prominence as a court artist under Tsars Alexander I and Nicholas I, was known for his dramatic equestrian scenes, often infused with ethnographic detail. His images of Cossacks, hussars, and irregular troops appealed to both Western fascination with the East and Russian imperial identity. Jazet, a master of aquatint and a tireless engraver of battle scenes and imperial iconography, brought these compositions to a French audience with remarkable technical finesse.

A striking example of this collaboration is the hand-colored aquatint titled:

COSAQUE IRRÉGULIER VÊTU DE HARDES DE FEMME QU’IL A PILLÉES("Irregular Cossack dressed in rags of a woman he has plundered")

Drawn by Alexander Sauerweid and engraved by Jean-Pierre Jazet, the image was published in Paris by Nepveu, a well-known bookseller located at No. 26 Passage des Panoramas. The scene shows a wild-eyed Cossack astride a galloping horse, dressed in a flamboyant and absurd mixture of female clothing, with spear in hand and wind tearing at his garb. While humorous in tone, the image also reflects deeper currents in French perceptions of the "barbarian" other, portraying the Cossack as both exotic and chaotic — a symbol of Eastern irregularity that had swept across Europe during the wars of 1812–1814.

The print can be interpreted as a satirical or propagandistic take on the feared Russian cavalrymen who had entered Paris in 1814. It also showcases Jazet's technical brilliance in aquatint, a medium he helped elevate to artistic heights through his work after masters such as David, Vernet, and Gros. At the same time, it reminds us of Sauerweid's ability to blend drama with detail, creating images that captured the imagination of two empires.

The popularity of such works, especially in series, points to the commercial vitality of military print culture in post-Napoleonic France. Publishers like Nepveu responded to contemporary tastes by marketing prints that offered both entertainment and moral commentary, exploiting the thin line between admiration and ridicule.

This sheet survives today as a curious and vivid document of its time: a window onto the ways war, empire, and identity were imagined, commercialized, and consumed in early 19th-century Europe.

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato