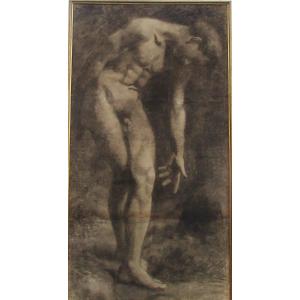

Reprise of the painting kept at the Capitoline Museum in Rome -

Several reasons can be given for this choice of Guido Reni concerning his work on the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian.

First of all, it was one of the rare occasions in Christian stories to paint the male nude (apart from the Christ's body, but which is a dead body), the latter being very poorly regarded and monitored by religious authorities.

The nude, accepted in mythological representations, was much less so in sacred paintings. However, it would be wrong to believe that this is only a game and a reflection on the body on the part of artists. From the 15th century, many "Saint Sebastians" were painted because several plague epidemics ravaged Europe: Guido Reni during his lifetime was able to experience two in Italy, while throughout the 17th century, the plague raged in our present-day France. Saint Sebastian, martyr and healer, was then invoked to drive out this scourge. Often, arrows pierced his groin and armpit, the area of the body where the first symptoms of the disease appeared. Modern views that have subsequently turned to this Saint Sebastian of Reni have seen him as a homosexual icon and have interpreted him in various ways.

First of all, the ambiguous attitude of the martyr is misleading. Pierced by arrows, he does not seem to be in a state of suffering. The slightly open mouth would suggest some prayers or inaudible groans, and the gaze turned towards the sky would almost betray a moment of pure ecstasy. Moreover, the arrow is in itself a phallic symbol par excellence. It is the “symbol of penetration, of opening. […] Moreover, Reni’s representation, and that of many other artists before and after him, does not exactly take Voragine’s account into account. Indeed, Sebastian is supposed to be a Roman soldier, a cohort leader; Guido Reni's Saint Sebastian is closer to the adolescent than to the virile man.

The ephebe then takes on an erotic dimension that some authors have noted. This was the case of Oscar Wilde who, during a trip to Italy in 1877, saw this work by Guido Reni.

He wrote about it: "The vision of Guido's Saint Sebastian, as I had seen him in Genoa, came back to me, a magnificent boy with thick brown curls and red lips, tied to a tree by his sinister enemies, although pierced by arrows, he raises his eyes full of divine passion in the direction of the eternal Beauty of Paradise which opens before him." He does not describe a man here but rather a "boy" in a sensual and ecstatic pose. The Japanese artist and writer Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) described in his autobiographical novel Confession of a Mask the realization he had of his homosexual desire after being aroused by a reproduction of a Saint Sebastian by Guido Reni

. This attraction even led Mishima to have himself photographed in the pose of the Baroque painter's ephebe. It is interesting to note the extent to which this Christian figure was able to produce a significant number of reproductions, imitations, texts, and painted and sculpted works by writers and artists. It would seem that the ambiguity of the feelings inscribed on the Saint's face, between holy ecstasy and pleasure of the flesh, inspired these artists.

However, this is indeed a modern look at the work, a decontextualization of Guido Reni's Saint Sebastian. The sacred has been ousted in favor of the body and youth of the ephebe.

The homo-normative character of such a representation. Saint Sebastian was reclaimed by the homosexual community primarily for his physical beauty but also for his protective character. Riddled with arrows and condemned for what he is and what he defends, Sebastian survives. His iconography is still very present in contemporary productions, both for its fantastical aspect but also and always as a representative and protective icon.

An article by Pauline Grazioli With a classical composition and in keeping with the pictorial tradition of his time, Guido Reni probably would not have imagined that his work, centuries later, would have sparked so much speculation concerning the sexuality of his saint. It is nevertheless true that, as a spectator, a certain attraction is felt in front of this painting.

A mysterious fascination took hold of me the first time I saw him: this body emerging from the shadows that capture him, this broad and luminous torso, this face where diverse feelings can be read... so many elements that still challenge me, that attract me and yet, seem to do everything to not make my understanding of him as clear as I had hoped. 1 ANDRE CHASTEL, L’art italien, 1998, Flammarion, p.420-421

Le Magazine de PROANTIC

Le Magazine de PROANTIC TRÉSORS Magazine

TRÉSORS Magazine Rivista Artiquariato

Rivista Artiquariato